THE AMAZING BUNGEE CAPER

How to Battle the Bungee Cord Blues

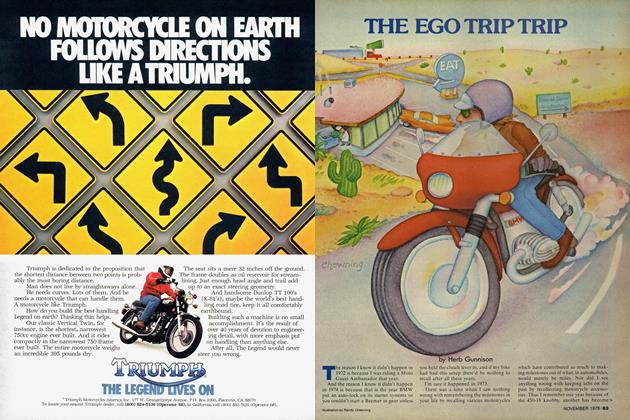

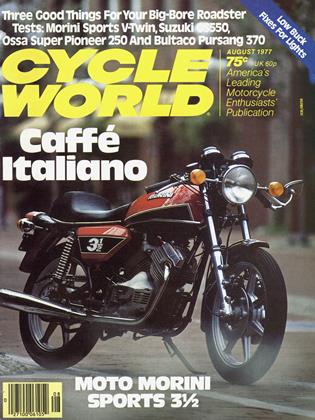

Herb Gunnison

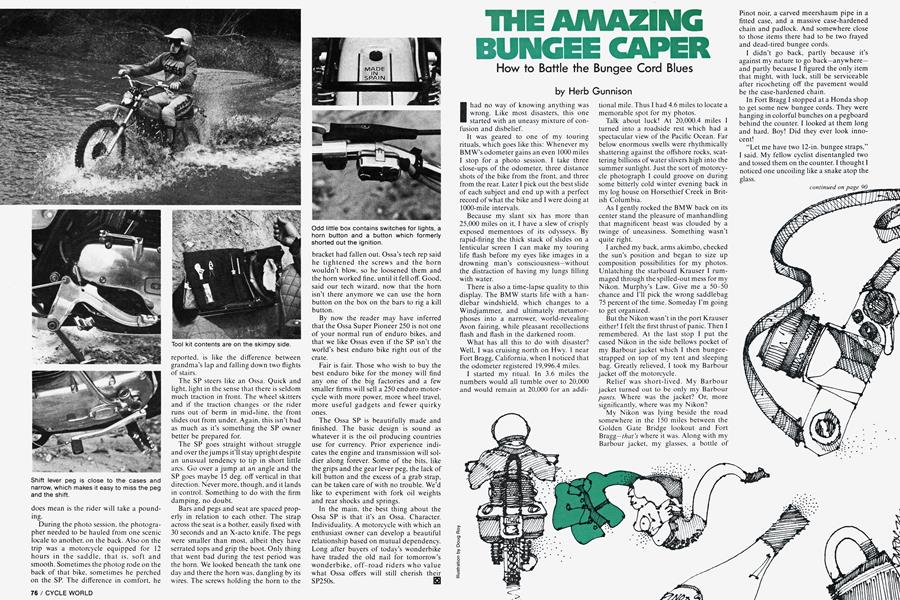

I had no way of knowing anything was wrong. Like most disasters, this one started with an uneasy mixture of confusion and disbelief.

It was geared to one of my touring rituals, which goes like this: Whenever my BMW’s odometer gains an even 1000 miles I stop for a photo session. I take three close-ups of the odometer, three distance shots of the bike from the front, and three from the rear. Later I pick out the best slide of each subject and end up with a perfect record of what the bike and I were doing at 1000-mile intervals.

Because my slant six has more than 25,000 miles on it, I have a slew of crisply exposed mementoes of its odysseys. By rapid-firing the thick stack of slides on a lenticular screen I can make my touring life flash before my eyes like images in a drowning man’s consciousness—without the distraction of having my lungs filling with water.

There is also a time-lapse quality to this display. The BMW starts life with a handlebar windshield, which changes to a Windjammer, and ultimately metamorphoses into a narrower, world-revealing Avon fairing, while pleasant recollections flash and flash in the darkened room.

What has all this to do with disaster? Well, I was cruising north on Hwy. 1 near Fort Bragg, California, when I noticed that the odometer registered 19,996.4 miles.

I started my ritual. In 3.6 miles the numbers would all tumble over to 20,000 and would remain at 20,000 for an additional mile. Thus I had 4.6 miles to locate a memorable spot for my photos.

Talk about luck! At 20,000.4 miles I turned into a roadside rest which had a spectacular view of the Pacific Ocean. Far below enormous swells were rhythmically shattering against the offshore rocks, scattering billions of water slivers high into the summer sunlight. Just the sort of motorcycle photograph I could groove on during some bitterly cold winter evening back in my log house on Horsethief Creek in British Columbia.

As I gently rocked the BMW back on its center stand the pleasure of manhandling that magnificent beast was clouded by a twinge of uneasiness. Something wasn’t quite right.

I arched my back, arms akimbo, checked the sun’s position and began to size up composition possibilities for my photos. Unlatching the starboard Krauser I rummaged through the spilled-out mess for my Nikon. Murphy’s Law. Give me a 50-50 chance and I’ll pick the wrong saddlebag 75 percent of the time. Someday I’m going to get organized.

But the Nikon wasn’t in the port Krauser either! I felt the first thrust of panic. Then I remembered. At the last stop I put the cased Nikon in the side bellows pocket of my Barbour jacket which I then bungeestrapped on top of my tent and sleeping bag. Greatly relieved, I took my Barbour jacket off the motorcycle.

Relief was short-lived. My Barbour jacket turned out to be only my Barbour pants. Where was the jacket? Or, more significantly, where was my Nikon?

My Nikon was lying beside the road somewhere in the 150 miles between the Golden Gate Bridge lookout and Fort Bragg—that’s where it was. Along with my Barbour jacket, my glasses, a bottle of Pinot noir, a carved meershaum pipe in a fitted case, and a massive case-hardened chain and padlock. And somewhere close to those items there had to be two frayed and dead-tired bungee cords.

I didn’t go back, partly because it’s against my nature to go back—anywhere— and partly because I figured the only item that might, with luck, still be serviceable after ricocheting off the pavement would be the case-hardened chain.

In Fort Bragg I stopped at a Honda shop to get some new bungee cords. They were hanging in colorful bunches on a pegboard behind the counter. I looked at them long and hard. Boy! Did they ever look innocent!

“Let me have two 12-in. bungee straps,” I said. My fellow cyclist disentangled two and tossed them on the counter. I thought I noticed one uncoiling like a snake atop the glass.

continued on page 90

continued from page 77

“That’ll be $3.50,” said my fellow cyclist.

“Three-fifty?” I replied, astonished.

“Yeah—I know—inflation. Cup-a-coffee costs 40C,” he apologized.

“Think nothing of it,” I said. “I once bought a pair of bungee straps that cost me somewhere in the neighborhood of $350— each.”

In spite of this experience I will readily admit to considerable bias regarding bungee cords. I like them. They are perhaps the last viable defense against the technological conspiracy to “auto-mate” the motorcycle.

It is, I know, a losing battle. Our changing language is an indication of where we are headed—or rather, where we are being pushed. Saddlebags are no longer saddlebags, but, in the words of one ad, touring luggage cases. Imagine yourself loping into Cheyenne, Wyoming at high noon, feeling tall in the saddle—with two ABS plastic touring luggage cases bolted to your cycle’s rump.

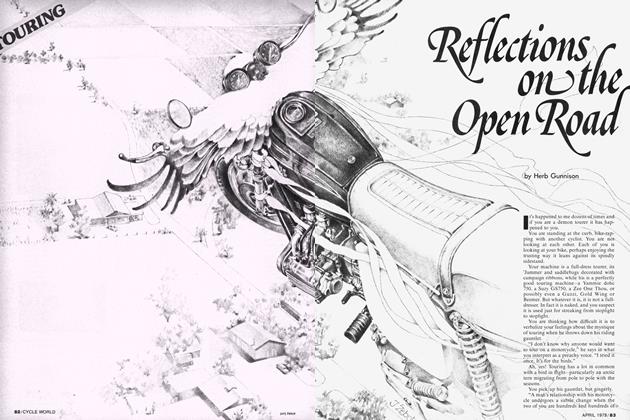

Don’t get me wrong. Panniers and fairing storage compartments are fine—indispensable, even, for the long-ranging tourer—but they give a sterile, too-wellorganized. automotive tone to a bike. On the other hand, when your tent and sleeping bag are bungee-strapped above the taillight, your rig takes on a gypsy tonecarefree, idiosyncratic, poetic, clockless.

By his bungees shall you know the true nomad.

But even if you don’t dig this image, putting a bulky tent or sleeping bag in a fitted luggage case is an uneconomical use of valuable storage space. And what do you do with a tent that’s soaking wet with dew? Lock it in a rubber-sealed plastic box with your dehydrated food, eh? Well, bon appétit; you may be dining sooner than you think.

Besides, dammit, it feels good to swing a boot over your house and your bed when they’re securely bungee-strapped to your mount. Yes, even if storm clouds are in the air and you know in your heart you’re going to spend that night in a motel watching Columbo, drying your gear while you commit gluttony with an 18-in. carry-out pizza.

That boot-swinging feels good, though, only if your house and bed are still bungee-strapped to your bike.

Bungee cords are sly. They’re always tensed for a caper, waiting until your back is turned to jettison whatever you leave in their care. Any touring rider who has never been overtaken by a friendly motorist who has just retrieved his tent, jacket, or whatever, is almost certain to be a tourer of limited experience.

This situation will probably never change, but it should be possible to reduce the frequency. Some facts and suggestions:

continued on page 94

continued from page 90

There are basically three types of bungee cords.

The first type, which is homemade, can be dismissed quickly. It consists of a series of loops cut out of an old inner tube and strung together. Writers specializing in touring subjects are fond of this suggestion because it doesn’t cost anything, but this is misleading. The cost of a bungee cord is proportional to the value of the equipment you lose if it fails. You are not in a nickel and dime situation. The inner tube you cut your loops out of already has two strikes against it. First, it fanned as a support for a tire. Now it’s fanning even as a used tube. Not only that, but each loop has two strikes against it.

The second type of bungee is round on the outside but the rubber core actually has the cross-section of a solid letter “u.” The core is then covered with a tough, colorful synthetic material which is braided and applied so tightly that the rubber core is compressed until it is almost round. Compressing the core keeps the outer sheath tight when the cord is stretched. Ingenious, eh?

This bungee material was used as shock

By his bungees shall you know the true nomad.

cord on aircraft landing gear before the first bungee cords appeared for motorcycle use. The first ones were fairly tough and the hooks were coated with rubber to prevent scratching. Over the years they have changed from a useful accessory for the serious tourer to a cheapo, fast buck minor accessory for the motorcyclist.

The only round bungee cords I could find when researching this article did not have the rubber-covered hooks and were a measly V4-in. in diameter, as opposed to some old bungees in my collection with a 5/8-in. diameter. These chintzy bungees are made in Hong Kong and in my opinion that is the only place you should use them. However, in all fairness they are ideal for strapping a pasteboard bakery box of meringues behind the seat, but should not be used for anything with more density, especially something with heavy fillingeclairs, for example.

The third type of bungee consists of an unprotected, flat, black rubber strap, which has a heavy uncoated wire hook running through a thick boss at each end. Truckers use them for tying down heavy tarps. They are ugly as uncooperative sin and have serious drawbacks. The hooks are murder on paint, vinyl, Naugahyde, and chrome, and because the rubber is uncoated they develop ozone cracks from the sun. However, when they are modified, chemically treated, and used with their shortcomings in mind, they are the only way to go.

continued on page 98

continued from page 94

The only way to go?

OK, look at the physics of the thing and. make up your own mind.

For simplicity I have limited my testing to the 18-in. lengths because they are representative of the differences between the round cords and the flat straps and 18 in. is the most versatile length. An 18-in. flat rubber strap requires a 50-lb. force to elongate it 7 in. and it still has lots of stretch, or life, left. An 18-in. round covered bungee requires only a 20-lb. force to elongate it a whopping 23 in., and it is then at the limit of its stretch.

The round cords feel more rubbery as they are stretched over a load, and this feels reassuring. But the laws of physics have no feeling: It is not the feel of the stretch but rather the pressure the cord exerts that holds your load in place. For example, it takes only 6 lb. to elongate an 18-in. round cord 7 in., as opposed to 50 lb. for the flat type. When the round cord is at the limit of its stretch—23 in.—it is exerting less than half the force of a flat strap extended only 7 in.

The flat straps offer advantages besides strength, providing you are willing to revamp them. A good way to begin modifying the flat straps is by removing the hooks and taking them to a large tool and die shop, or machine shop, and having the hooks dipped into the rubbery solution used to protect delicate cutting tools after machining. The warm material forms a cushioning layer on the wire which prevents paint scratches and fabric tears. Have each hook double-dipped for added protection. Alternatively you can buy a length of small diameter plastic tubing and slip it over the wire hooks.

To prevent ozone cracks occasionally spray the straps with Armor All or another preservative. I stretch them while spraying on the theory that the protective chemicals will penetrate further into the pores. Armor All also lubricates the rubber so the cord will slide over objects easier, equalizing the tension. Finally, if age cracks do develop, you will notice them when the rubber is stretched. At the first sign of cracks cut the strap into 16 pieces.

Fooling around with ugly black rubber straps may sound tedious, but it’s preferable to having a pretty braided synthetic sheath lending an air of good health to a strap that is rotting at the core. As the core slowly decomposes to the consistency of overcooked macaroni you pull it even tighter to compensate. Then one day you pause for a series of even-thousand-mile photos, and. . . .

OK. Flat, black, heavy-duty rubber bungees. Modified, treated, monitored. What else?

Loads are tied on the back of motorcycles under static conditions. But when the bike is moving the load is subjected to surprisingly dynamic forces—jouncing, wind pressure, and compression from the bungee straps. Creases in a jacket get sharper, a water-heavy canteen slips into the curves between the tent and sleeping bag, and each time the load rearranges itself the straps equalize the tension along their lengths. The longer a strap is, the more loosening of tension there is likely to be, particularly when it is looped and brought back around the luggage rack bars in several places. Short straps cannot loosen proportionately as much: Their only contact with the luggage rack is with the hook at each end and they must of necessity be routed more directly across the load.

continued on page 100

continued from page 98

In the present state-of-the-art, bungee straps leave you between a rock and a hard place. Round bungees get you in trouble because as their long stretch is reduced under a settling load their force greatly lessens. Short flat straps may fail because settling uses up all their short stretch and they unhook.

It would be nice if some enterprising manufacturer would come up with a bungee strap with a stretch factor scientifically adjusted to the length (more for short, less for long, but both forces heavier than the round-type cord) and with a coated springloaded latch on each end. But until that day dawns, here are some common-sense bungee rules based on the premise that we can buy a bike off the floor that will consistently get us a quarter of a mile in 12.3 seconds, but we can’t buy a bungee off the wall that will consistently get us home with all our belongings.

1. Make sure every item is under more than one strap.

2. Thread the strap through loops, sleeves, knotted shoelaces, etc. Add loops to stuff-sacks if they don’t have them.

3. Don’t put a heavy item such as a cast iron frying pan on a compressible item like a jacket or pad.

4. Put valuables in saddlebags. Only an imbecile would trust an expensive piece of equipment, such as a Nikon camera, to his bungees.

5. If you want to be a pro, buy 50 percent more bungees than you think you need, for starters.

6. Do your bungee shopping on payday.

7. If you’re a perfectionist, hand craft your own bungees. It is now possible to get the flat black material off a coil at so much a foot. The hooks are sold separately. Try the bigger hardware stores or large gas stations that cater to trucks.

Above all, try to develop a philosophy regarding bungee straps. When you’ve finished loading, inspect your job critically. Is there anything under the tiedowns you’d be sick over losing? Don’t jump on your bike and promise yourself you’ll check every few miles. What happens is that, sure, you check it every few miles—for a few miles. Nothing appears to be shifting. Each time you look back you become more confident that the load is secure. Finally your mind turns to other more interesting things, and you ignore the load—just when it’s beginning to come unglued.

continued on page 102

continued from page 100

Now, armed with your new bungee suspicion, are you ready for “The Amazing Bungee Caper?”

OK. Hold on.

You’re cruising. If you weren’t on the bike you’d be in a dead run. It wasn’t dumb then, but it sure as hell is dumb now, that you miscalculated. As usual you made too many side trips, so you’ve been shagging ass since dawn because you’re going to be late—real late—getting back to work.

You twist around in the saddle and check the bungees. They’re doing just fine.

This hasn’t been your day. You haven’t owned a minute of it. The crosswind has been gusting at easily 60 kilometers per hour. Motorists following you seem to be fascinated at the way your bike leans over to parry the thrusts, and they’ve been tailgating in order to have a front row seat if you go down. You ran out of talcum powder at noon and your brain and your bum are not on speaking terms. The sun has been slanting into your scratched goggles all afternoon and the elastic strap is shot so you’ve had to push them up on your nose every few minutes—the cyclist’s variant of the Chinese water torture.

You're tired.

On top of everything else you’re damn near broke which means you can’t afiford a motel tonight. You’re strictly traveling now—out for all the miles you can get—and wish you didn’t have to mess with all the camping gear even in the convenience of a commercial campsite. You’ve been 300 miles on this tank and will need some motion lotion in the next 50 miles and if you don’t score on a Shell station where your only credit card is valid you’re not even going to be able to afford a KOA unless you stop eating.

Your goggles drop down around your neck. Would be great to buy a new pair in the morning. You burst out laughing. Here you are, you idiot, riding a $5000 motorcycle which is running like a million dollars, and you can’t afford to buy a pair of goggles!

It’s late in the day and you’re approaching Tonopah, Nevada, moving north on Hwy. 95. The sun is low and your elongated shadow is leading you by a wheel length. You can race your shadow' on a winding road. “Hey. shadow, we’ll race you to Tonopah!”

Suddenly, wow! A Shell station! The owner is locking the door. You flip your turn signal; he unlocks the door. While the bike is being refueled you stretch your legs. Tonopah is 6000 feet above sea level and there is a chill in the air. You undo the bungee cords and take your Barbour suit off the rack. Then you re-tie the load, stretching and hooking your flat, black, modified bungees over your house and your bed, trying to remember all the rules you read in CYCLE WORLD magazine.

You ease onto Hwy. 8A, pointing the Metzlers toward Battle Mountain. You’re cruising again.

You take off your goggles and, holding the throttle on with your left hand, you turn and fasten them under two bungees. That crossover throttle maneuver should be illegal but you do it anyway with satisfaction. You check the bungees. The load is doing just fine. The wind has stopped. Except where the quartz-halogen says it isn’t, it’s pitch dark.

This may not have been your day, but your mood is changing. You’re going to own this night; you earned it. It’s bought and paid for.

Your world is sensational. The bike is standing still. Only the earth moves, accelerating as it rushes by on the straights and tilting in exquisite balance in the curves. The beautiful high beam indicator glows like a mood light. You couldn’t feel more luxurious if you were being chauffeured to the opera in a Bentley. You listen to the rhythmic music of the opposed Twin and the soughing of the wind it creates.

You turn and check the bungees. The load’s doing just fine. You’re not tired any more. You can cruise all night and forever. You swipe a timeless hour from forever and get away with it; and another, and still another.

Then it happens. You’ve just taken a long fun look backward through the red glow of the taillight, mesmerized by the road disappearing behind, until you got scared and turned back to the Avon.

Suddenly, from out of nowhere, you get that familiar old Paul Revere feeling. The British aren't coming and the fate of a nation is not riding with you—but it is midnight by the village clock when you storm into Battle Mountain.

You feel the Revere kinship because your midnight ride is a freedom ride too, in its way. For a few brief, incredible moments you are winning the fight against the oppression of schedules, of order, of reason, money, decay, and conformity.

Then you turn to check your bungees. And your rack is bare.

You are never ready for the Amazing Bungee Caper. Without stopping, you unhook the mike.

“Breaker, breaker, this is KRV one zero zero zero, the Easy Rider, c’mon.”

It’s late, but who knows, some good buddy might be following with your house and your bed.

Using the CB to call for help has pretty well shot the Paul Revere image. But what the hell—Paul Revere never had to deal with bungee cords.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue