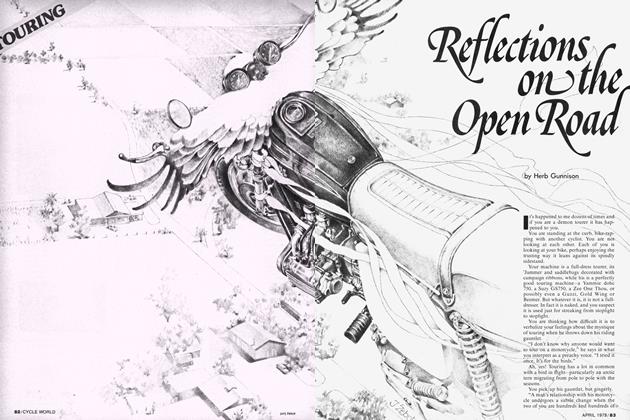

THE OLD BOLD ENDURO RIDER

It might be dangerous to quit!

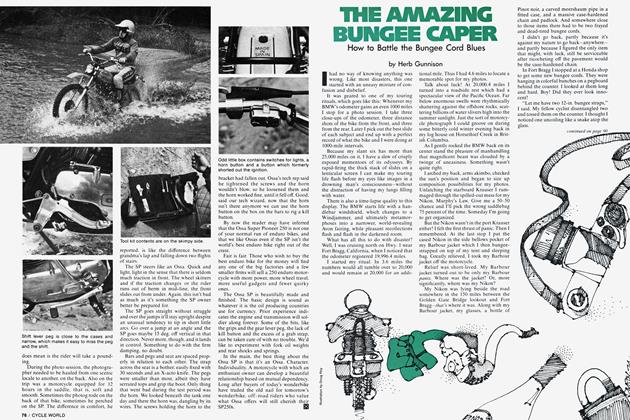

by Herb Gunnison

It was 22 years ago. It was before the 5.40x18 knobby, before "Loc-Tite," duct tape and Silicone Seal, yeah, if you can believe it, it was even before the ring-ding revolution.

It was a week before the Jack Pine Enduro and I was showing signs of prerace nerves, particularly at night when instead of sleeping I’d lie awake wondering how hard I could push myself for 500 miles.

Age was on my mind. I’d just turned 35. “Joe, how much longer do you think we can ride competitively?” I asked, as I reassembled the Amal.

“I’m 34, and I think I’ll hang up my boots after this run—they’re worn out anyway,” he answered without emotion. His lack of emotion bothered me even more than his plans to quit. How could he talk so matter-of-factly about giving up a sport he loved?

Sure, he had his reasons. I respected that. But still I wondered if he was trying to grow old gracefully or was just growing old before his time. Which cliché a man decided to live with could have a profound effect on the balance of his life.

Reaching a critical point in the assembly of the Amal I snapped the small spring clip into the second tiny notch from the top of the needle valve.

“With National Champion Bill Baird as my witness, I’m going to compete until I can’t see the notches on the needle valve with my naked eye,” I swore to Joe, to myself, and to my Triumph.

And the next day I bought a new pair of lineman’s boots.

Twelve years ago I was getting my Triumph ready for the Jack Pine—those old four-strokes took a lot of getting ready. I was working alone. Joe had hung up his worn-out boots nine years before and traded his Triumph in on a “Hardly-Ableson” golf cart. It was shortly after my 45th birthday and I was assembling the Amal in my garage.

Suddenly with a shock I realized I couldn’t see the notches on the needle valve clearly. I fought off an impulse to fake it. No, there was too much at stake.

My 10-year-old vow came back to haunt me.

I took the needle valve and clip out in the driveway, held them up to the sun at arms’ length, and snapped the clip into the second notch from the top.

I made another vow on the spot. I’d never work on a carburetor in the shade again.

But I also swore, doggedly, out of some vague sense of self-preservation, to uphold my original vow. At some point in my life there had to be an end to this madness.

Seven years ago I was working on my Husky, getting ready for the Little Burr enduro. I couldn’t see the notches in the needle valve clearly even in the bright sunlight—even at arms’ length.

Crisis time. Crossroads with no arrows.

I wasn’t quite ready for the big enduro in the sky, but in the enduro of this life I was running 60 minutes late and had just whiskered a plug with 10 miles of tight woods and swamps ahead.

And sure as hell there would be a check át the end of the section.

I remembered my 15-year-old vow. Should 1 quit? I forced myself to add up the pros and cons.

With immense relief ! discovered there weren’t any cons. The pros were:

1. I’d already sent in my entrance fee, which was about 12 clams.

2. My two major vow's were made w hen 1 was 35 anti 45. What, I asked myself, did a snot-nosed kid of 35 or even a callow boy of 45 know' about life? 1 was now 50 and a man matures a lot between 45 and 50,

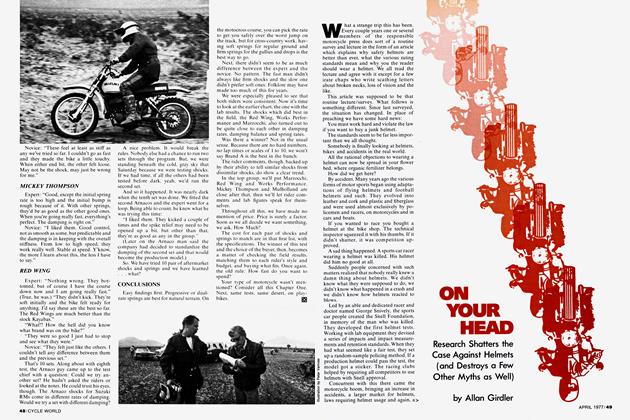

Every run has a few guys everyone calls “Pop” and they usually hang in there pretty well.

particularly if he is an enduro rider. I’d take a mature decision over an immature one, any day. Besides, how could I have known I’d feel so good when I was 50?

3. What w'as all this needle valve malarkey anyway? 1 never worried about running into needle valves when dodging through the woods—trees, yes, but trees are a zillion times bigger than needle valves, and I had to admit I could still see trees as well as ever.

So, I decided it would be prudent to quit when I couldn’t see the trees—or perhaps the forest.

However, in view' of my track record wdth vows, I decided not to swear to it.

Yeah. But when should you quit?

No one can answer that question. Yet 1 think it is possible to agree about one or two things.

First, the decision to quit should not be a snap judgment. Many an enduro rider has quit before his time because he made up his mind right after a particularly rough and unlucky ride. Many older riders no doubt quit just because it happened to be raining on the day of the event.

It is certainly not premature to start monitoring your attitudes and your physical condition in your early or mid-thirties. A lighter bike, special exercises for certain parts of your body, picking and choosing your enduros, and being w illing to face up to the inevitable need for such adjustments are necessities.

A commonly held belief, rarely verbalized, is that you quit when the danger becomes so great it outweighs the joy of competition. The same injury that sidelines a kid for the following Sunday might put an older man out of business for a month, and during that miserable month, reservations about the validity of the sport are bound to crop up.

What kind of danger applies only to older riders? Wipe-outs caused by ageworn reflexes can be counted out because coordination diminishes very slowly even into late middle age. Moreover, you automatically compensate for what little difference there is in reflex sharpness.

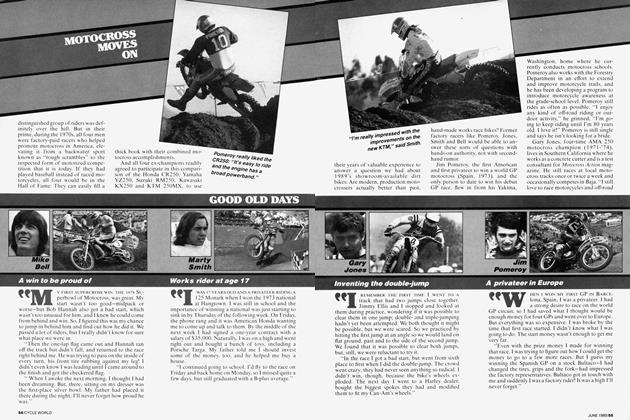

More to the point, perhaps, is the fact that every region has its share of middleaged competitors who obviously are not suffering from lack of coordination. Lew' Atkinson won the Jack Pine w hen he was 44 and lost the overall wán on a tiebreaking check when he was 45. John Buftaloe and Sox Brookhart still remain strong contenders for the overall and they have been in the senior class for years. Then there’s John Penton, whose exploits before and after he was 40 are legendary. Every run has a few' guys everyone calls “Pop” and they usually hang in there pretty w'ell.

No, if you want to quit, chances are you’ll have to think of a better excuse than “deteriorating reflexes.”

If you are healthy and active but stop competing because you feel you are getting “older,” you may be committing psychological suicide.

And for the rider with a deep love of competition, quitting too soon may be the most dangerous way to go.

The heart is not the mysterious organ romantic poets claim it is. The heart is just a.muscle. You cannot overstress a healthy heart. If the muscle is accustomed to w'orkouts and you flog hell out of it pushing your bike up a greasy off-camber hill, nothing dire happens. You run out of breath before you run out of heart. Those collapsed riders of all ages strewn up and down “block and tackle hill” or that tired cliché “cardiac hill” are not having heart attacks.

They’re just catching their breaths.

What could be more fair than that?

No, if you want to quit enduro riding you’ll have to think of a better excuse than your “poor heart.”

Listen carefully to the nuance of that little voice that says, “Better not compete. Quit while you’re ahead” and you’ll notice a curious thing about it. It utterly lacks desire. Pay no attention to it. It is the voice of numbness and oblivion, the siren call from the bleachers, cajoling you to join the spectators.

Counter that voice by getting the pain of desire going. And keep it going.

When you’re young, desire is automatic. This is great while it lasts, but as you grow older you’re in deep trouble if you assume it will always be so.

If we assume that desire is the name of the game and that if you take care of desire you will find ways to keep doing w'hat turns you on, then it is helpful to have rules, and for what it’s worth, here are mine:

Rule 1. When exercising, I try to keep my compulsion in mind and remember it is for a higher purpose like enduro riding. I have known for some time that we cannot always live in climax situations. Trite as it may sound, they have to be earned, but while preparing myself for the great moments in life I figure I might as well enjoy the thrill of anticipation.

Rule 2. For each mile I plan to ride in an enduro I must ride my 10-speed bicycle one mile. Yup, for a 400-mile enduro I will pedal 400 miles within two weeks of the run. This is in addition to cow'-trailing on my Maico. If this seems excessive, remember there aren’t many 400-mile enduros and they do demand special conditioning.

If I decide to ride 100 miles, I must ride

I have known for some time that we cannot always live in climax situations. Trite as it may sound, they have to be earned.

the first 50 away from home. That way I can’t chicken out of the second 50 miles.

Rule 3. I can w'atch TV any time I want, for as long as I want, except that whenever Fm w'atching I must be pedaling against a % drag on my exerciser bicycle. Sometimes I do a little cheating, but I never cheat after the first of March. By spring I’m rarin’ to go. This is important—even crucial, because the older you get the harder it is to get back in shape if you have allowed your body to lie fallow through the winter.

That’s all there is to the rules. I can go just as hard—even harder—than I could at 35, but I’m in better shape than I was 22 years ago. It seems the older I got the more hooked I became on exercise until I reached the point where my w'orkouts w'ere building me up faster than age was tearing me dowm. I know this cannot go on forever but I’m not thinking in terms of forever: I’m thinking only about the next enduro and, well, sure, the one after that.

But it’s funny. Lately I’ve noticed I don’t trophy any more. I said I could go harder, not faster.

Finally, at long last, a reason to quit.

Quit when you’re no longer winning.

That is the most stupid reason of all for quitting.

How' many enduros have you w'on? Come on, I mean overall? You don’t stop riding because you don’t win overall so why stop riding just because you’re no longer winning trophies? If you have enduro riding in your blood, you ride for other more important and less obvious reasons.

What are some of those reasons?

Enduro riding is a loner’s game. It is not a spectator sport. It is not for glory seekers. You are personally responsible for an incredible number of vital decisions that affect your mental and physical well being. You are hanging in there for long sections of woods, rocks, water and time. The longer you hang in there the more alone you become. The trail becomes less and less obvious—beautiful! You are enduring where others before you have dropped out or been passed. You know you are unbeatable. Unbeatable, that is, except for little mistakes. You sashay four times around five stumps and leave your left footpeg imbedded in the fifth stump for the following riders to grimly shake their heads at. Thank God for the new boots. Each log, lob lolly, rocky riverbed and godawful hill has retained an intangible part of your spirit but that fifth stump hit the jackpot. It got a $12 trick peg. The trail peters out to almost nothing and you must now be in the top 10. Then come the skid marks and half-donuts. You’re lost (lost?) and there is no one to show you the way. Your left leg feels like a hip boot full of water. Back-tracking you pick up the arrows. No. It can’t be. They’re making you go down there? Your body and your subconscious are crying out, in their voiceless way, for rest, for surcease, for an end to this inhuman struggle. In the middle of nowhere you almost run over the checkers—their own fault for hiding like that! Another four points shot to hell but they know all you care about is how much farther it is. Lead has replaced the water in your left hip boot. It’s the last check, and you’re told with sympathy and encouragement that there are just 10 more miles to go. Checkers are not spectators—they are part of the deal and you’re grateful. Ten miles. Suddenly you’re not tired any more. You can ride that standing on the pegs. Correction: peg. You stand on the right peg for all of 200 yards. You smear the speedo face with your wet glove. Back on key time! Relax and cool it. The trail drops gently down to a gravel road. Turning right, the world spinning, you lay a long and unnecessary arc in the gravel with the rear tire in well earned exultation. Now you pop along at good old 24, slouching sideways on your bike with your left boot skimming inches above the blurring gravel. It’s been a long day, a great day. You remember sliding out on the dew-wet grass just before the first check—you knew better but that early morning sun was fierce like someone was electro-welding your fork crowns on the run. Seems like a long time ago. Did that happen on this run?

continued on page 104

continued from page 84

You wave to a man riding his lawnmower and he waves back. It’s great to be alive. Then, ahead, people. Lots of people milling around. God, what a sight. The home check. Home at last. Time for shooting the breeze.

“Hey, did you see that poor guy’s peg sticking out of that stump backward?’’

A sudden burst of laughter.

“I don’t know why I’m laughing—that was my peg!”—and more laughter.

All the enduros you’ve ever been on come rushing back at you, and you wonder if you’ve trophied. Probably not. It was a big run and you lost a bundle when the chain broke in the middle of the Rifle River. Why you? The classic enduro question. For anyone else it would have happened while the bike was parked at the noon control. And you bet everyone else bought trick pegs without any manufacturing defects. Well, anyone can sashay five times around five stumps.

A heavy man detaches himself from the crowd and heads straight for your bike. He has a cigarette in one hand and a can of beer in the other. He is roughly 30 pounds overweight. It appears that at some vague point in his young life he lost his desire to compete in anything at all and decided he was more comfortable as a spectator. Discovering he had a talent for this, as the years went by he worked harder and harder to earn his spectatorship. Finally he reached his goal and turned pro. After a few years on this plateau he reached the zenith of his profession and became an intellectual spectator. Now, in addition to merely watching others do things, he asks provocative questions without feeling the need to respond in any positive way to the answers. He is usually waiting for you at the end of the run. He smiles broadly and offers you a beer.

“Say, friend, how the hell old are you anyway?”

“37—46—50—55, whatever.”

“Man, I’ll bet you’re tired.”

“No, not too bad.”

You look at him and smile warmly, meaning it. Different strokes for different folks. You ask around, comparing scores and quickly learn enough to know you did not trophy. It doesn’t matter. What you feel goes far beyond that, into the heart of existence.

This feeling is one of the advantages of being an aging enduro rider.

There are others as well. For one thing, when one of those ratty split-expansion chambered ring-dings is making too much racket you can turn down your hearing aid.

Which reminds me: Do you know who makes the best hearing aid on the market?

Maico, who else? |§j