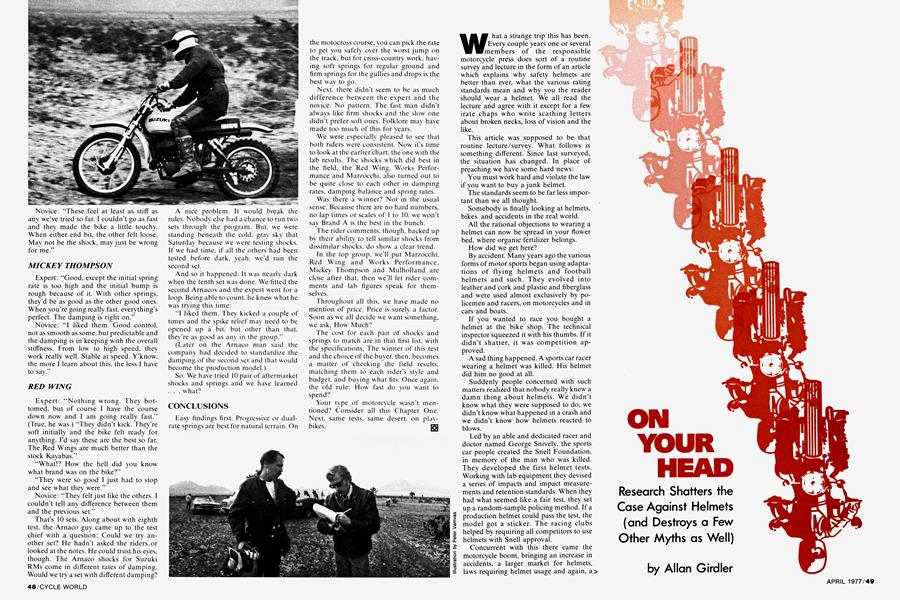

ON YOUR HEAD

Research Shatters the Case Against Helmets (and Destroys a Few Other Myths as Well)

Allan Girdler

What a strange trip this has been. Every couple years one or several members of the responsible motorcycle press does sort of a routine survey and lecture in the form of an article which explains why safety helmets are better than ever, what the various rating standards mean and why you the reader should wear a helmet. We all read the lecture and agree with it except for a few irate chaps who write scathing letters about broken necks, loss of vision and the like.

This article was supposed to be that routine lecture/survey. What follows is something different. Since last surveyed, the situation has changed. In place of preaching we have some hard news:

You must work hard and violate the law if you want to buy a junk helmet.

The standards seem to be far less important than we all thought.

Somebody is finally looking at helmets, bikes and accidents in the real world.

All the rational objections to wearing a helmet can now be spread in your flower bed, where organic fertilizer belongs.

How did we get here?

By accident. Many years ago the various forms of motor sports began using adaptations of flying helmets and football helmets and such. They evolved into leather and cork and plastic and fiberglass and were used almost exclusively by policemen and racers, on motorcycles and in cars and boats.

If you wanted to race you bought a helmet at the bike shop. The technical inspector squeezed it with his thumbs. If it didn’t shatter, it was competition approved.

A sad thing happened. A sports car racer wearing a helmet was killed. His helmet did him no good at all.

Suddenly people concerned with such matters realized that nobody really knew a damn thing about helmets. We didn’t know what they were supposed to do, we didn’t know what happened in a crash and we didn’t know how helmets reacted to blows.

Led by an able and dedicated racer and doctor named George Snively, the sports car people created the Snell Foundation, in memory of the man who was killed. They developed the first helmet tests. Working with lab equipment they devised a series of impacts and impact measurements and retention standards. When they had what seemed like a fair test, they set up a random-sample policing method. If a production helmet could pass the test, the model got a sticker. The racing clubs helped by requiring all competitors to use helmets with Snell approval.

Concurrent with this there came the motorcycle boom, bringing an increase in accidents, a larger market for helmets, laws requiring helmet usage and again, a need for people to know how to tell good from bad. A government committee worked out a set of standards, some states did the same and the more reputable (a generalization, I know) helmet manufacturers formed a trade association, the Safety Helmet Council of America (SHCA). In general they adopted the federal guidelines and established a certification program, so a helmet buyer would have some way of being sure there had been an attempt to provide the protection he was after.

Things went like this for a couple years. The Z-90 standard was revised and improved and the Snell standard likewise. There developed two parallel lines of testing, with the Z-90 guidelines representing the mass market with a conscience and Snell being the banner waved by hardcore helmet boosters and racers.

There were some other philosophical differences. The federal committee decided vision was an important enough factor to be included in the standard, so they specified that the average head must have at least 120 deg. of vision from within the helmet. The Snell Foundation believed (still does) that more coverage was more likely to be a benefit, so when Bell introduced the complete coverage Star model, with 107 deg. vision on the median head, Snell approved it and the feds didn’t. And when the several states got into the standards business, many of them went along with the federal guideline—a word used several times here for reasons which will be explained—and issued helmet regulations with the 120 deg. clause included.

The mandatory helmet usage laws which came into vogue a few years back brought along some controversy of their own. Motorcycle riders are known for being individuals and individuals seldom welcome being told what to do, for their own good or not. On the opposite side no politician can resist taking bold and decisive action which sounds fine to the public and only has a real-life effect on a few people. When those few people are socially suspect anyway, the political rewards are even better.

We had two fields of impassioned argument. There was the idealistic Constitutional one; can the government protect people from themselves and should the government do so if it’s legal? The other question is matter-of-fact; are helmets really good anyway?

About those helmet standards. They were drawn up by experts in the field, by men working without much previous experience. They are lab tests. We don’t need details here. The important thing was that the helmet certification and research people drew up their tests as lab tests.

If you instrument a form the size and weight of the human head and drop it from a measured height onto a cubic yard of concrete, you will have a certain and known impact on that form.

If you put that instrumented form inside a helmet and drop it from the same height onto the same block of concrete, the instruments will tell you what the impact was, in terms of g force, so many times the force of gravity. When you know the size and shape of the blow to the unprotected head form, and to the protected head form, you can know the protection.

Set a spike in the concrete and drop a weighted helmet on the spike from a set height and you'll know how well the helmet shell resists being penetrated.

So. We had standards for helmet performance.

We had various state laws controlling helmet usage.

We had some laws and some guidelines about certification, mostly voluntary.

We knew a lot about how helmets performed in the lab.

We argued helmets and their use on faith.

This is a lot of flaws. While the people involved in the research and the enforcement and perhaps the usage were people of good faith and good intentions, there were gaps.

Enforcement was haphazard. If a manufacturer didn’t wish to have the Snell Foundation test his wares, he didn’t have to. Same for the SHCA. If the helmets had no stickers, why, racers couldn’t wear them. If some shoddy outfit joined SHCA and flunked the tests, the council could revoke his membership and take away his stickers.

That left the quick-buck guys with only a few million potential customers. You can guess how hard they worried about that.

Just as serious was that nobody really knew enough about what a helmet should do in real life. Drop tests in the lab may be just like a thrown rider landing on the curb head first. But they may not be like that, either.

And when the pro vs. con debate came back again and again, each side believed they were arguing fact and they weren’t. Nobody really knew.

That’s the way it was last time we looked.

Things have changed. They’ve changed so much it’s hard to believe we went this long without the changes.

Begin with the end of one major guideline. The federal government now has its own helmet standard, known as DOT-218. (DOT is short for Department of Transportation, under whose auspices the federal highway safety people work.)

As a standard, DOT-218 is pretty much like what used to be known as the Z-90 standard, with limits for performance under impact, penetration and retention.

But DOT-218 is not a guideline. It is a law. That law says anybody who makes or sells for use on public roads a helmet which doesn’t meet DOT-218, has the feds for an enemy.

The federal government is a bad outfit to have against you. Failing Snell or SHCA is one thing. They throw you out of the club. Violate federal law and they seize your bank account. Or your person. They go after your customers if you’re a manufacturer or your suppliers if you’re a retailer.

And the feds are everywhere.

As a result, no prudent person will make or sell a helmet inferior to DOT-218.

An imprudent person can still buy a junk helmet. There are rumored to be sharpies still hanging in there. They find an undeveloped country with cheap labor and they order a pile of trashy, flashy helmets. Tip-toe through the border, a quick tour of the alleys and swap meets and their business is done.

Caveat Emptor. Meanwhile, the new rider, the man or woman who does want a good helmet, something an expert has had a chance to inspect and test and certify, can find one easily. Without effort and without prior knowledge. Even those of us who don’t like consumerism, we who doubt that the average person needs all the protection pushed at us, can still approve of this.

If helmets work.

That brings us to the next good news. We can know if helmets are good, if they work and how well, only when we know what happens out there on the street.

We are close to finding out.

Nobody ever said the lab was the answer. Until now there was no known correlation between the tests and the accidents. There were surveys and some research but because there wasn't money for the complete job, there was no complete job.

Thanks to the various safety and consumer campaigns, the money has been made available. The U.S. Department of Transportation has funded a motorcycle accident research program at the University of Southern California’s Institute of Safety and Systems Management. This is the most complete and careful and thorough such project ever done. It deserves an article of its own and there is one included in this review package.

We are concerned here with helmets, their use and their effectiveness. Suffice it to begin with the fact that the accident study is professionally done, by trained investigators who are also motorcycle riders. The study is funded to do a complete, even exhaustive, investigation of 900 motorcycle accidents involving injury in the greater Los Angeles area. This is a controlled sample in that the reports will be on the first 900 such accidents to occur during the funding’s time period, that is, they can’t pick the good ones or the gory ones or adjust in any way.

The project is incomplete at this writing. The research group has completely processed more than 300 accidents.

A 300-accident survey is a large enough sample to use for preliminary conclusions, especially when the trends are as clear as they are in this case.

Begin with helmet use: California has no mandatory helmet law. Between 45 and 50 percent of the riders wear helmets voluntarily. The 50 percent of the riders who don’t wear helmets have 70 percent of the accidents which result in injury.

Hypothesis: Wearing a helmet is an admission of accepting a risk. Riders who admit bikes are dangerous are less likely to be hurt than bikers who don’t.

In half the accidents with injuries, there were no head injuries. But. Of the bareheaded half who hit their heads, half received a concussion ... or worse.

There were 100 riders who received injuries in crashes, and whose helmets showed marks of impact or abrasion. Of that 100, a total of two, yes, two, suffered concussions.

Hypothesis and headline: Helmets Work.

There is the other extreme. There have been fatal accidents in this study.

Hugh H. Hurt, Jr., principal investigator for the research group, phrases his findings this way: “I have seen accidents where a helmet would have done no good.

“I’ve never seen a helmeted rider die of a blow to the head.”

Helmets work.

Considerable stress has been placed on that because the next findings are something of a blow to those of us who’ve followed and believed in the various helmet standards all these years.

One of the prime advantages of the USC project is that it will compare helmets in real life to the helmets in the lab. The researchers can know, for example, that a 150-lb. man went over the bars at 22 mph, sailed 30 ft. through the air, hit a board fence head first and emerged with a headache.

continued on page 95

continued from page 51

They can take his helmet back to the lab and know exactly what shape the helmet is in. Then they can subject the helmet to a blow which duplicates the shape the helmet is in. Finally, they can match that blow, that is, the g force to the helmet vs. the g force to the head, against the standards.

Preliminary evidence indicates that the effect of the various standards is less than expected. If the rider’s head isn’t struck at all, no problem. And if the blow is unsurvivable, the grade of helmet makes no difference.

The middle ground is the important ground. While the research clearly shows the benefits of helmets, the benefit of the top-grade helmet as compared to just any helmet, isn’t showing up in the figures.

Naturally, there is reduced injury and some riders in Snell helmets have headaches while the same crash in a tired old helmet would have given them a concussion. but these results are discussed in percentage points.

This is hard (for me) to accept.

Reacting as a survivor of the soup-bowl era and as a rider who has refused to wear anything except a Snell-approved helmet since the Snell Foundation was formed, I didn’t want to know that my $75 hand-laid fiberglass shell racing-legal helmet wasn’t three times as safe as the $25 DOT-218 polycarbonate shell helmet sold at the corner store.

Dr. Hurt takes a more balanced view.

The helmets built to higher standards are better helmets, in that they can be counted on to absorb more impact. Even if the odds are that the extra protection won’t be used, still, it’s nice to know it’s there.

At the same time, helmet laws and standards should be based on the greatest good for the greatest number. Motorcycling will gain, for riders and the public, if the lessexpensive helmets do their job.

Point taken and conceded.

And now, assuming the reader is one of us who wears a helmet because we’ve always known helmets work, on to the bright side.

The anti-helmet people have made some telling arguments. Helmets are heavy, so it makes sense that a helmet could pendulum your head into an injury. Arguing in favor of loss of vision or hearing is difficult. And it’s all too easy to visualize a helmet snagged on a bumper.

These things could happen. Such accidents are possible. Ever since helmets became worth wearing, those of us who wear helmets have accepted the above possibilities as risks worth taking because not wearing a helmet was more risky. We were wrong.

Know how many crashes surveyed were caused or complicated by impaired vision or hearing?

None.

How many helmets snagged and hurt the rider?

None.

Neck injuries? Riders with helmets have slightly fewer neck injuries than riders without helmets. James Ouellet, who does the injury follow-up studies for the project, says if he cared to play games with the figures (he doesn’t) he could make a statistical case for helmets reducing the risk of .cervical injury.

The figures up to now show the safety helmet to be cleaner than the seatbelt, in that belts can and do cause minor injuries while saving lives and helmets save lives while doing no harm at all.

In sum, anybody who can afford to buy gas can afford an adequate helmet, and . . .

There’s no good reason not to wear a helmet. 0