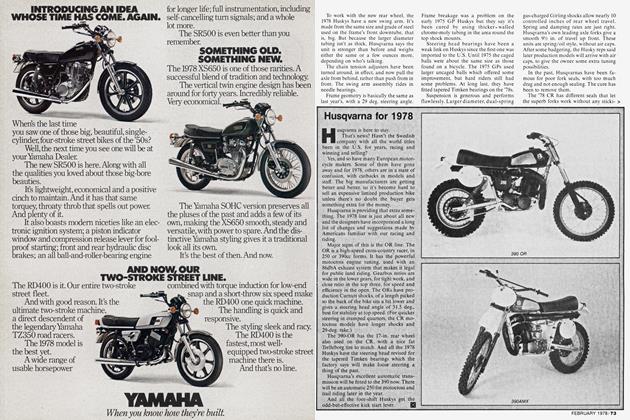

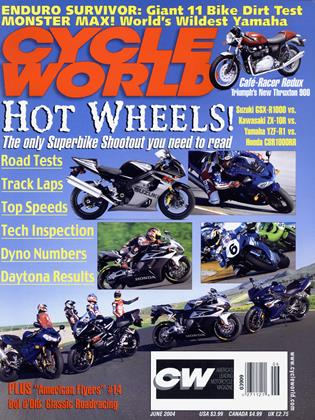

Triumph Thruxton 900

FEATURES

Café-Racing, made better than new

ALLAN GIRDLER

WE FEW, WE favored few, we band of enthusiasts who are plain darned tired of letting all the ink, all the R&D and more than half the big-bike market go to those boring cruisers, at last we can take heart.

Triumph, a.k.a. The Other 100-Year-Old Motorcycle Company, has taken modern components and mixed them with a radical fashion from the past, and presto, it’s a new Triumph Twin on the correct side of being something completely different.

The model’s name is Thruxton 900, which segues us into some background.

In the 1950s and ’60s, when Yank enthusiasts were inventing drag racing and turning TT machines into a pioneer version of street-trackers, known then as bobbers and choppers, the Brits were putting their creative efforts into road-licensed versions of circuit racers. Postwar England had more road space than traffic, hard though that is to believe now. The ’50s version of Extreme Sports was to kit Triumphs, Nortons, Beezers and the like with souped-up engines, rearset controls, clip-on or “ace” handlebars that canted the rider into a crouch, and then take these machines out on the road.

Speaking of hard to believe, England’s highways then had no speed limit. The fun was to top 100 mph, “the ton” they called it, and to race from one truck stop to another. The stops were known as cafés, and the motorcycles in this activity were.. .café-racers.

Two-wheel sport has generated fear and trembling in the general public since the days of the bicycle. To make matters more newsworthy, the café-racer crowd became known as Rockers and they feuded with kids in fancy dress, riding scooters, who were nicknamed Mods. The punch-outs sold millions of tabloid newspapers and caféracers were known worldwide.

About the time the fad began to fade, as prosperity filled the roads and the young men got jobs, families and cars, the major factories noticed the trend and experimented with it. Honda’s café-bike, a CB350 with Yoshimura engine and GP bodywork, never went on sale. HarleyDavidson’s try, the XLCR, was the slowest seller in H-D’s lineup and never mind that a certain Willie G. Davidson designed it.

The final segment of history useful here is that when production racing was at its most popular and competitive, one of the season’s highlights was a 500-mile race at Thruxton, a fast and sweeping, 2.3-mile circuit in the Hampshire countryside south of London. Triumph won the race several times and just as they named the Bonneville 650 for records on the salt and the Daytona 500 for wins on that track, so did the factory issue a limited run of 650 Twins, fitted with special heads and such, and named Thruxton (see “Proddy Racer” sidebar). Best of all, in 1969 a Thruxton won the 500, in a Triumph sweep of the podium.

Enter the Present: The big motorcycle-makers whip out new engines, frames and models on what seems a daily basis. The smaller firms, as in BMW, Ducati and, yes, Triumph, fill out their model lines with variations using the same basic parts.

Triumph returned to the classic vertical-Twin with the revived Bonneville, understandably the best seller from its 2001 intro on. Then came the T100, same 790cc motor, but with more chrome, paint and extras like rubber kneepads. Next the Triumph America quasi-chopper, using offset crankpins for a Harleyesque exhaust note, even rear footpeg mounts that imitate a Harley toolbox-in cruiser styling, form strangles function.

With the Thruxton 900, though, all this can be forgiven. Its vertical-Twin uses the original cases, heads and so forth, but the bore is increased by 4mm, taking the displacement from 790 to 865cc, rounded off as factories do to 900.

The 900 has a 360-degree crankshaft, which gives an even firing order at the expense of a primary imbalance, and relieves the imbalance with twin balance shafts. Camshaft timing is moved to work better higher in the rev range, the carburetors are bigger and the exhaust system first lacks the kink that purists derided on the revived Bonnie, and second features upswept megaphone-style mufflers.

The result, according to the Triumph engineers, is 69 horsepower at 7250 rpm. In part because the Thruxton’s compression ratio is 10.2:1, peak torque is 53 foot-pounds at 5750 rpm. Comparable figures for the stock Bonneville are 61 bhp at 7400 rpm and 44.3 ft.-lbs. at 3500.

Clearly a major gain, and it’s worth predicting here that the Thruxton stage of tune could easily be used for the Bonneville and the T100.

The Thruxton shares the Bonneville’s frame and suspension, for the most part. The Thruxton’s fork is pulled back, tuned for higher speeds and loads, and the rear shocks are longer. Rake and trail are 27 degrees/3.8 inches, compared with 2974.6 in. for the Bonneville, and the Thruxton’s wheelbase is shortened more than half an inch, 58.1 from 58.8. What this means is quicker steering, aided here by an 18-inch front wheel with a shorter and wider footprint that sharpens response to rider input.

Claimed dry weight is 451 pounds, with a fuel tank capacity of 4.2 gallons, again shared with the other Twins.

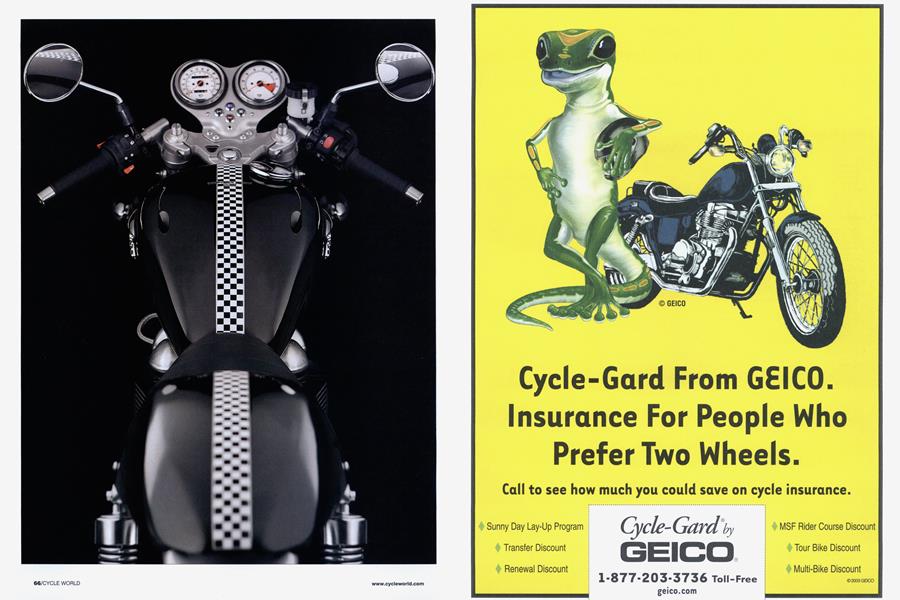

For style, the fenders are shorter and the engine covers are polished. For tradition, the handlebars are clip-ons. The footpegs and levers are moved back, dictating the classic racer crouch, and the passenger pad is covered with a replica of the hump featured in production racing back in the era that inspired the new Thruxton.

The longer shocks have raised static seat height a fraction, so it’s slightly higher than the Bonneville’s, nearly 3 inches higher than the America’s.

In keeping with modem marketing, Triumph presented a full line of accessories and extras at the model’s introduction. Said launch took place at the fabled (for some of us older chaps) Ace Café, a tmck stop on London’s outskirts that was a hangout in the café-racer period, then closed, and has now been revived and is the center for old-bike rallies and things like festivals for American hot-rods and rock ’n’ roll. At the top of the options list is a pair of less-restrictive mufflers, “off-road-only” please, and good for 6 or 7 bhp. And there’s a classic flyscreen, tank pads, chrome goodies, a tme solo seat, stepped seats, saddlebags, tankbag and even a centerstand.

ON VIEW

The Thruxton looks exactly as it should, with all the clues any café-racer enthusiast will spot. The “pea-shooter” mufflers look good, the hump on the seat is right, and so forth. Better, there are no awkward notes, no fake stuff slathered on for effect. We’re so used to radiators that the large oil-cooler belongs in front of the engine. The silly juke in the exhaust pipes is gone, all the small parts integrate into the whole, and when the new model was parked at the Ace next to old bikes, nothing jarred the expectations. Good work all ’round.

ON TRACK

By no coincidence at all, the press intro then moved to the Thruxton circuit. The track, still used for racing, is wide, flat, sweeping and fast. Triumph booked the circuit for the day so all we had to worry about were our peer journos, all of whom behaved themselves on this occasion, even the daredevil Italians, usually good for at least one crash-and-bum.

The first lesson here was that the Thruxton 900 is a completely modem motorcycle, as up-to-speed as it looks. With flawless electrics and all the mod-cons, the current Triumphs-in company with the current Harleys, BMWs and Ducatis-are as far from the old leakers and lurchers as they can be, again something daily riders will appreciate, and don’t bother telling us about character, not ’til you’ve pushed your classic home in the rain.

So, the Thmxton proved an easy starter, light and clean on the controls, with good power all the way up and down, and because this was a track session, it’s safe to report that the bike will reach redline in top, something well above the classic 100 mph. Steering is precise and predictable, and there’s enough ground clearance for any cornering speeds within reason.

If a flaw had to be found-and that’s what we reporters are there for, eh?-under heavy braking tipped into a turn the Thruxton tries to stand up, maybe a result of the steep rake and reduced trail, but nothing that can’t be coped with.

The counterbalancers work. There’s vibration, nature’s way of telling you the engine is running, but it’s never intrusive. There’s no buzz at the mirrors, nor tingle at the grips.

ON THE ROAD

High spirits having been served, the press and factory reps hit the road, those wonderful English secondary lanes that surely contributed to the evolution there of sport motorcycles and sports cars. (Nearly forgot to mention that although another brand claims patronage of The Almighty, when Triumph goes on tour with a new machine, it’s bright and sunny two days straight, no kidding.)

Riding on public roads allows reflection and doesn’t mask reactions with adrenalin, which means the rider is more aware of minor discomforts. For instance, the ignition switch is sited barely in front of the left grip, on the headlight ear, directly away from the rider.

The reach is awkward and annoying and must have happened because they swapped bars and didn’t think the project through.

Further, the clutch cable makes a sharp turn as it exits the perch. This doesn’t hamper clutch action, but it’s bound to affect cable life.

The narrow bars tuck the mirrors in, which reduces the angle of vision to the rear and, sure, racing bikes don’t have mirrors, but on the road they’re useful.

The sporting posture dictated by the bars, pegs and “ton-up” image works at speed. The crouch reduces wind resistance and the rider can lean into the airstream. But leaning forward puts the instruments and warning lights below his field of vision. Checking the panel requires a deliberate look down. Adding to that, the tumsignals don’t cancel themselves. They can’t be heard and they can’t be seen and more than one press rep blinked for miles until hooted into action by his peers.

None of this is major and most of it applies to any motorcycle fitted with roadrace controls.

Maybe the options list should include a milder bend of bar, a couple inches of rise, say 30 inches tip to tip, somewhere between the 34 inches of the Bonneville and 28 inches of the clip-ons? That one minor change would help a lot in the ride.

ON THE FUTURE

That deftly introduced the next question: Who will buy the Thruxton 900? Triumph’s marketers expect the model to attract enthusiasts who’ve been out of the market, former Britbike owners perhaps, who either would like to replace the Triumph they had back when, or can now get the Triumph they didn’t get then because school or work came first. Sounds like a good way to bet.

The caution here is that history tells us the café-racer was big in England, had some impact in Europe proper and barely made a ripple crossing the pond. Harley’s XLCR sat for years in showrooms and only became a cult bike because the people who create cults pick objects the public has rejected; that’s how they prove to themselves that they’re smarter than the rest of us.

Honda studied the café-racer market (see adjacent article for details) and decided to invest in dual-sport and motocross models instead, a good move. Yamaha produced a neo-classic 500 Single in the English mode. Didn’t sell. Much later, Honda countered with an equally authentic 500 Single, right down to the black-and-gold paint, read Velocette. Didn’t sell.

But those were past imitations. This is now and the real thing, a sporting Triumph from the chaps who virtually invented sport. The true verdict must wait for buyers with checkbooks in hand, but in the meantime a brisk, clean, fast Triumph Twin that starts with a button, doesn’t leak and will sound just right soon as the off-road kits get here, is, as they say, safe as houses.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Up Front

Up FrontSecret Daytona

JUNE 2004 2004 By David Edwards -

Leanings

LeaningsWhat To Do In Winter

JUNE 2004 2004 By Peter Egan -

TDC

TDCA Short History of Chassis Flex

JUNE 2004 2004 By Kevin Cameron -

Departments

DepartmentsHotshots

JUNE 2004 2004 -

Roundup

RoundupMonster Max!!!

JUNE 2004 2004 By Steve Anderson -

Roundup

RoundupFormula Bmw: K-Bike Power For F-1 Hopefuls

JUNE 2004 2004 By Kim Wolfkill