SLANT ARTISTS

Uphill all the way

ALLAN GIRDLER

SKIPPING PAST THE official history for now, the first hill-climb is bound to have been a happy accident.

And we know how it started, because we all have a riding buddy who can’t resist a challenge. Say he can’t and he’ll do whatever it takes to prove he can. So it must have happened that a couple of guys are riding along in the belt-drive, single-cylinder, pedal-’til-she-fires era when one sees a steep hill and says to the other, “Bet you can’t climb that.”

It was uphill from then on. The history book says the first “official” hillclimb took place in May, 1903, in New York and it was won by Glenn Curtiss, who went on to accomplish more feats than we can list here.

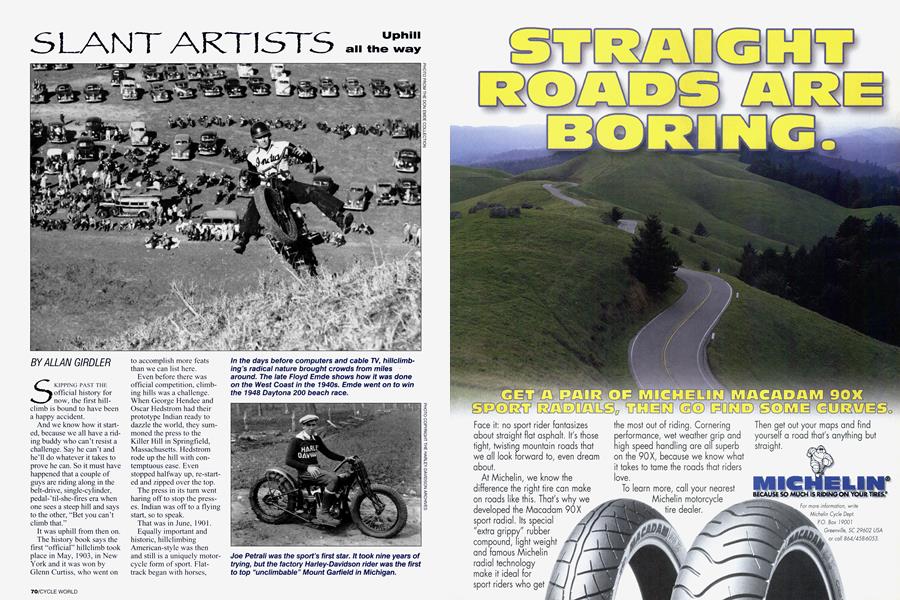

Even before there was official competition, climbing hills was a challenge. When George Hendee and Oscar Hedstrom had their prototype Indian ready to dazzle the world, they summoned the press to the Killer Hill in Springfield, Massachusetts. Hedstrom rode up the hill with contemptuous ease. Even stopped halfway up, re-started and zipped over the top.

The press in its turn went haring off to stop the presses. Indian was off to a flying start, so to speak.

That was in June, 1901.

Equally important and historic, hillclimbing American-style was then and still is a uniquely motorcycle form of sport. Flattrack began with horses, after all, likewise for crosscountry racing and point-topoint. Cars race around ovals and on closed roadlike tracks. But only motorcycles climb hills. (Okay, to be really fair, that climb Curtiss won in 1903 was actually a timed run up a paved, steep, public road.)

What hillclimbing was, was natural, and easy to organize and stage and take part in. Right after that 1903 climb, clubs and groups nationwide began finding roadless slopes, 40 to 60 degrees in banking, 200 to 600 feet long. They marked the finish line and the starting line, paid the farmer for the use of his land, and away they went.

In the early days, until 1920 or so, the machines were road bikes or racing models, run without many changes. There were famous climbs-San Juan Capistrano, California, being the best known-but the simple challenge of getting up any hill was enough to permit climbs on, for instance, Long Island, New York, or outside Fresno, California, neither a location where you’d predict much of a mountain.

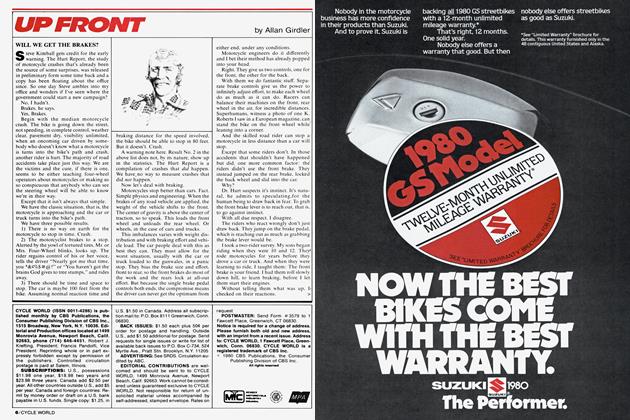

Hillclimbing’s peak (can I get away with that?) came between 1920 and 1935. As bikes got better the hills got smaller, so they moved to places where the slope was the steepest. There used to be a national championship at Mount Garfield, Michigan, but after Joe Petrali, perhaps the supreme slant artist, topped it with his Excelsior, they moved the event to Muskegon, where there was more challenge.

The purpose-built hillclimbing motorcycle appeared in 1923, when the Excelsior team took a racing (as in dirt-track) V-Twin, stretched the wheelbase a couple of feet, then swapped a metal tractor band, a paddle affair, for the rear tire.

They won. And as no racing fan will be surprised to hear, the sanctioning body banned such modifications.

The ban didn’t stick. There were three factories then. Excelsior followed that first winner with a new model, a 45 that outdid the 61s and 74s from the other camps. And then Excelsior built a special run of 15 overhead-valve 45s, burning alcohol and cranking out 50 horsepower.

Harley-Davidson and Indian followed, making special ohv engines and using modified dirt-track frames, with the seats and tanks pushed as far forward as they could go. In those days the AMA assigned national championship status, so there’d be a 10-mile national on a mile track here, and a 10-mile national on a half-mile track someplace else. There was no official hillclimb champion. Except that in 1932, Petrali contested all available venues and because he’d racked up the most points he was declared the national dirt-track titlist and the Eastern U.S. Hillclimb Champion.

Then, as flat-track faded with the 1930s economy, with roadracing as such not really invented yet, with TT still an occasional romp through the woods, and with hillclimbing the most popular branch of the sport, with classes for Amateurs and Pros, for 45s, 61s and, yes, four-cylinder machinesthat’s where the nowlegendary Ace made its reputation-with all this going on, history went the other direction.

Production racing is what happened. They called it Class C, and because nobody could afford a racing motorcycle, the rules required streetbikes. They worked fine on most tracks, and brought new people into the sport and the stands. Class C saved racing.

What couldn’t be done, not the way the Excelsior, Harley and Indian specials did it, was climb hills on your Sport Scout or WD.

Okay, some did it. The classes remained and there were racers, Sam Arena for one and Hal Mathews for two, who could take those big Twins, jam the throttle open and rocket to the top. Much later came riders like Malcolm Smith, who’d two-stroke up and over with such grace you almost forgot there was a hill there. But by then the crowds were someplace else.

Today’s hillclimbers are bigger and badder and louder than ever, the sort of steppers, as they say in Texas, for which there are no hills.

Riders don’t get the press or the money and glory, not like they used to. But their challenge, accepted at the drop of a flag or the click of a watch, is the oldest heritage in all of racing. □

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Up Front

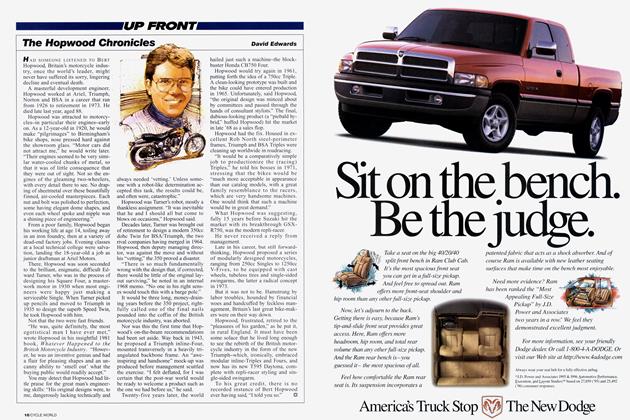

Up FrontThe Hopwood Chronicles

March 1997 By David Edwards -

Leanings

LeaningsHow Many Bikes Do You Really Need?

March 1997 By Peter Egan -

TDC

TDCPractical Men

March 1997 By Kevin Cameron -

Letters

LettersLetters

March 1997 -

Roundup

RoundupYamaha Shows Wonder Thumper!

March 1997 By Steve Anderson -

Roundup

RoundupTraction Calling

March 1997 By Don Canet