The Hopwood Chronicles

UP FRONT

David Edwards

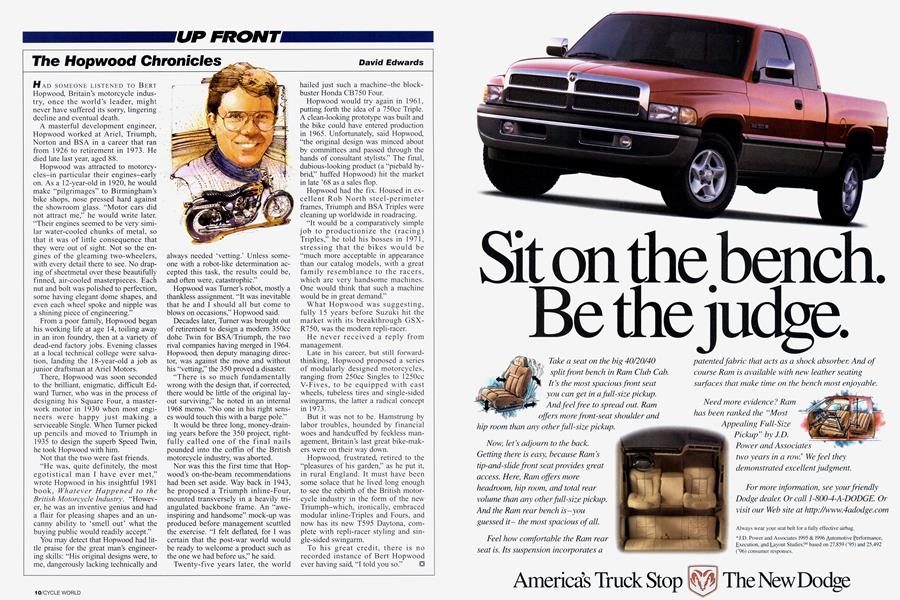

HAD SOMEONE LISTENED TO BERT Hopwood, Britain’s motorcycle industry, once the world’s leader, might never have suffered its sorry, lingering decline and eventual death.

A masterful development engineer, Hopwood worked at Ariel, Triumph, Norton and BSA in a career that ran from 1926 to retirement in 1973. He died late last year, aged 88.

Hopwood was attracted to motorcycles-in particular their engines-early on. As a 12-year-old in 1920, he would make “pilgrimages” to Birmingham’s bike shops, nose pressed hard against the showroom glass. “Motor cars did not attract me,” he would write later. “Their engines seemed to be very similar water-cooled chunks of metal, so that it was of little consequence that they were out of sight. Not so the engines of the gleaming two-wheelers, with every detail there to see. No draping of sheetmetal over these beautifully finned, air-cooled masterpieces. Each nut and bolt was polished to perfection, some having elegant dome shapes, and even each wheel spoke and nipple was a shining piece of engineering.”

From a poor family, Hopwood began his working life at age 14, toiling away in an iron foundry, then at a variety of dead-end factory jobs. Evening classes at a local technical college were salvation, landing the 18-year-old a job as junior draftsman at Ariel Motors.

There, Hopwood was soon seconded to the brilliant, enigmatic, difficult Edward Turner, who was in the process of designing his Square Four, a masterwork motor in 1930 when most engineers were happy just making a serviceable Single. When Turner picked up pencils and moved to Triumph in 1935 to design the superb Speed Twin, he took Hopwood with him. Not that the two were fast friends.

“He was, quite definitely, the most egotistical man I have ever met,” wrote Hopwood in his insightful 1981 book, Whatever Happened to the British Motorcycle Industry. “However, he was an inventive genius and had a flair for pleasing shapes and an uncanny ability to ‘smell out’ what the buying public would readily accept.”

You may detect that Hopwood had little praise for the great man’s engineering skills: “His original designs were, to me, dangerously lacking technically and always needed ‘vetting.’ Unless someone with a robot-like determination accepted this task, the results could be, and often were, catastrophic.”

Hopwood was Turner’s robot, mostly a thankless assignment. “It was inevitable that he and I should all but come to blows on occasions,” Hopwood said.

Decades later, Turner was brought out of retirement to design a modem 350cc dohc Twin for BSA/Triumph, the two rival companies having merged in 1964. Hopwood, then deputy managing director, was against the move and without his “vetting,” the 350 proved a disaster.

“There is so much fundamentally wrong with the design that, if corrected, there would be little of the original layout surviving,” he noted in an internal 1968 memo. “No one in his right senses would touch this with a barge pole.” It would be three long, money-draining years before the 350 project, rightfully called one of the final nails pounded into the coffin of the British motorcycle industry, was aborted.

Nor was this the first time that Hopwood’s on-the-beam recommendations had been set aside. Way back in 1943, he proposed a Triumph inline-Four, mounted transversely in a heavily triangulated backbone frame. An “aweinspiring and handsome” mock-up was produced before management scuttled the exercise. “I felt deflated, for I was certain that the post-war world would be ready to welcome a product such as the one we had before us,” he said. Twenty-five years later, the world hailed just such a machine-the blockbuster Honda CB750 Four.

Hopwood would try again in 1961, putting forth the idea of a 750cc Triple. A clean-looking prototype was built and the bike could have entered production in 1965. Unfortunately, said Hopwood, “the original design was minced about by committees and passed through the hands of consultant stylists.” The final, dubious-looking product (a “piebald hybrid,” huffed Hopwood) hit the market in late ’68 as a sales flop.

Hopwood had the fix. Housed in excellent Rob North steel-perimeter frames, Triumph and BSA Triples were cleaning up worldwide in roadracing.

“It would be a comparatively simple job to productionize the (racing) Triples,” he told his bosses in 1971, stressing that the bikes would be “much more acceptable in appearance than our catalog models, with a great family resemblance to the racers, which are very handsome machines. One would think that such a machine would be in great demand.”

What Hopwood was suggesting, fully 15 years before Suzuki hit the market with its breakthrough GSXR750, was the modern repli-racer.

He never received a reply from management.

Late in his career, but still forwardthinking, Hopwood proposed a series of modularly designed motorcycles, ranging from 250cc Singles to 1250cc V-Fives, to be equipped with cast wheels, tubeless tires and single-sided swingarms, the latter a radical concept in 1973.

But it was not to be. Hamstrung by labor troubles, hounded by financial woes and handcuffed by feckless management, Britain’s last great bike-makers were on their way down.

Hopwood, frustrated, retired to the “pleasures of his garden,” as he put it, in rural England. It must have been some solace that he lived long enough to see the rebirth of the British motorcycle industry in the form of the new Triumph-which, ironically, embraced modular inline-Triples and Fours, and now has its new T595 Daytona, complete with repli-racer styling and single-sided swingarm.

To his great credit, there is no recorded instance of Bert Hopwood ever having said, “I told you so.” U

View Full Issue

View Full Issue