The 15 million dollar motorcycle

CYCLE WORLD ROUNDUP

DAVID EDWARDS

If you haven’t heard much lately about Harley-Davidson’s much-heralded Nova project, that’s because

development of the bike is, in the words of a company spokesman, “at a brick wall.”

Make that a $15 million brick wall. Because that’s how much money it’s going to take to get the new bike into production.

For those readers who haven’t kept abreast of the Nova, a little background information. The project began more than six years ago when Harley decided it needed a new type of motorcycle, something that would carry the company into the future and at the same time appeal to a wider spectrum of riders than the “time-honored” V-Twin models. Harley’s engineers laid out the engine specifications, then farmed out the actual drawing-up of plans to the enginedesign division of Porsche Design, a subsidiary of the

West German sportscar firm. Not much is known about the engine except that it’s a liquid-cooled V-Four. That’s all Harley spokesmen are letting out, although they will tell you, ÍQ the best corporate PR fashion, that the engine has some “unique design characteristics” and is “mechanically, very unusual.” Little more is known about the rest of the bike. Those at

bike and are willing to talk say that while the Nova is very much a unique motorcycle, it has the crisp feel of an Italian sportbike and makes a sound “unlike any Harley ever.” The consensus of opinion about the styling is that this new Harley will be a standard-style motorcycle, and not just standard-style in the Harley-Davidson sense of the word, either. We’re talking about a genuine non-custom, do-everything, non-specialized kind of bike—a “standard,” if you will, the impending death of which Cycle World Editor Paul Dean lamented in his September editorial.

Certainly, there will be a cruiserbike version, given the popularity of that style of bike right now, but there’s a twist of irony here: HarleyDavidson, the company that

laid the groundwork for the Japanese-built customs that now own a lion’s share of the market, is on the verge of selling a standard, a type of machine that once was the only style of motorcycle built by the Japanese but that is now all but forgotten.

The reason that Harley officials are shying away from offering only a custom-style version of the the Nova is that they don’t want a sales conflict with their old-style V-Twins. In fact, they hope that the new bike won’t take away from the current VTwin line at all. Rather, they are aiming the Nova directly at the Japanese-bike rider, the kind of person who would like to buy American, but wants something different than Harley-Davidson presently has to offer.

And Harley hopes that part of the reason for buyers to switch will be price. The Nova engine was designed from the outset to be a costeffective unit to manufacture, something that the V-Twin Harley engine, which has design roots that go back to the first part of the century, is not. Thanks in large part to this allegedly easier-to-build engine, the word at the factory is that the Nova will be “price-competitive” with the Japanese bikes.

Whether or not the Nova gets to go into sales battle with the Oriental bikes remains to be seen, though. As

things stand now, the Nova, which has gone through three distinct phases of development, is a working, completed prototype. What Harley wants to do now is set up a production line, build a batch of test bikes, make changes as needed, then get on with the building and selling of their new motorcycle.

And that’s where the $15 million brick wall comes in: Harley doesn’t have that kind of money. Indeed, in 1981 and 1982, the first years after Harley bought itself back from AMF, the company was in dire financial straits. The past two years have been better, but even with H-D making money, there’s no way it can come up with that much capital. So, with the Nova’s plans rolled up under their arms and their corporate hats in hand, Harley executives have gone looking for investors; and they’ve found that people with access to that much money tend to be conservative with it, particularly when it comes to the financing of new motorcycles.

And that’s how things stand now. Harley-Davidson has a motorcyle that American riders have been asking for but that American investors have so far been unwilling to bankroll. Don’t give up hope, though; Harley is still looking. As one company spokesman said, “We’re talking to anybody. You’ve got money, we’ll talk to you.”

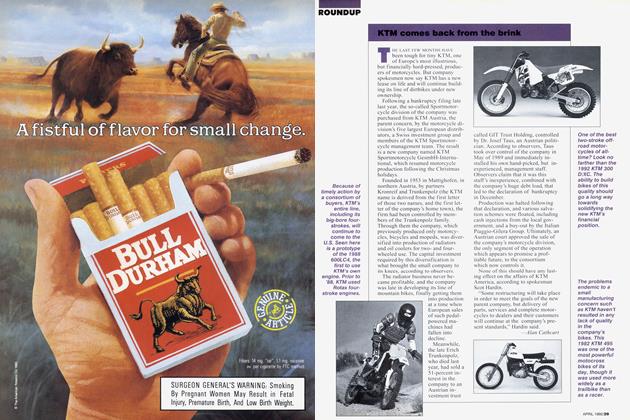

Honda CRs for '85

Everyone knew it would eventually happen. It was just a matter of time before some company would unveil the first production Open-class motocrosser with liquid-cooling. Well, the wait is over, because Honda has just re-

vealed its 1985 motocross lineup, and right at the helm is—you got it—the liquidcooled CR500R. And there’s more news; the CR60R is missing from the lineup because of inadequate sales, and the remaining models—the 80, 125, 250 and, of course, the 500—have a very long list of changes.

For starters, the Pro-Link suspension systems of the 125, 250 and Open bikes have been redesigned, with new, flatter progression curves and longer shocks. The changes allow a lower-rate shock spring that also weighs slightly less. The Showa fork used on the 250 and 500 is basically unchanged from ’84, while the 125’s Kayaba fork has slightly more travel.

Although they appear little-changed, the aluminum swingarms of the three larger bikes are actually quite different for ’84. The box-section arms are tapered so they are larger and stronger near the pivot point than they are at the rear axle. The 250 and 500 use a common swingarm that’s the same length as last year’s; the 125’s arm has been extended 7mm for ’85.

Several other dimensions have been jiggled and altered, too: The 125’s steering-head angle isn’t quite as steep as it was last year, and on all three big bikes, the distance from the swingarm pivot to the steering head is longer. The 125, 250 and 500 also share motor changes such as bridged exhaust ports to reduce piston-skirt breakage, new porting specs, new main bearings with steel bearing separators (replacing the troublesome plastic bearing separators used in ’84) and cases that are stronger at the cylinder-case junction.

The three machines also have new flat-slide Keihin carburetors, a 34mm for the 125, 36mm on the 250 and 38mm on the 500. The new carbs are claimed to increase throttle response and sport a couple of unique features:

The flat-slide carburetor bodies flare out at the top so conventional screw-tops can be used; the flat slides (actually more of a smashed oval shape) are made of zinc that’s been chrome-plated (instead of the normal chrome-plated brass), and the throttle-stop screw has been eliminated in favor of an air-bleed-type idle adjustment that is changed by turning the top of the choke knob. The zinc carburetor slide is lighter than a brass slide, while the airbleed idle system is claimed to be more precise than a stop-screw type.

There are a whole gaggle of smaller, but important, updates on the ’85 125, 250 and 500, such as larger front axles, bigger spokes and larger radiator shrouds. Aluminum brake shoes replace ones

made of magnesium, and the normal Honda brake squeal is said to be eliminated as a result. Reshaped seats, redesigned side numberplates and different fuel tanks change the looks of the CRs slightly, though the bikes retain the same basic Honda appearance.

Along with the across-theboard improvements, each model gets individual refinements: The 500 has a new kickstarter ratio and longer kickstart lever for easier starting. And the machine’s claimed horsepower output jumps from 58 to 60. The 250 has a new pipe and a redesigned ATAC chamber, which mounts under the pipe like on the CR125 and uses a simpler linkage system than last year’s 250. Most of the 125’s components are larger this year, including the ATAC chamber, the main bearings, the rod bearings, the wrist pin, and the crank weights. The new engine develops a claimed 32 horsepower at 11,500 rpm.

The CR80R wasn’t immune from the sweep of changes, either. The smallest CR features a redesigned engine that is claimed to have more power and rev higher. Like on its larger racing cousins, the 80’s Pro-Link ratios are revised and the links pivot in needle bearings. A new Kayaba shock with increased shaft travel helps boost rearwheel travel to a claimed 10.6 inches. Honda says the 33mm-stanchion front fork has 10.2 inches of travel.

The list of changes goes on and on, making it sound as though Honda has changed every aspect of all four machines. But actually, the reason there are so many small changes is because Honda didn’t make one large change—such as redesigning all four CRs—like it did last year. Honda’s 1985 motocross philosophy is one that stresses building on existing framework, and on proven designs. That’s a new policy for Honda: refinement rather than reinvention.

A quarter-century of meeting the nicest people

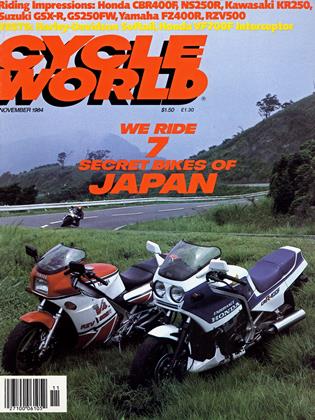

If ever a company was deserving of the phrase, “You’ve come a long way, baby,” it’s American Honda, the U.S. subsidiary of Honda

Motor Co., Ltd., which is celebrating its 25th year of doing business here.

It was in 1959 that Honda, a company started 11 years earlier with Soichiro Honda’s life-savings of $2700, decided it was going to invade the American market, dominated at that time by largedisplacement bikes from Triumph, BSA and Harley-Davidson. The company set up a beach-head in Los Angeles, occupying a tiny storefront showroom. There were eight employees, each trying to convince customers to buy from a six-bike lineup headed by the ubiquitous 50cc Super Cub step-through.

Things were tough that first year. Out of Honda’s world-wide output of 280,000 bikes, just 1732 were sold in the U.S. Only 15 dealers could be persauded to sell the Hondas, and a lot of those were hardware stores, hobby shops and sporting goods stores. The sales picture got better in a hurry, however: Within two years, Honda had the best-selling line of motorcycles in the country. That position was further solidified in 1962 with the introduction of what has been called one of the most successful advertising campaigns in history, the famous “You meet the nicest people on a Honda” slogan.

Today, Honda’s motorcycle production is 3.18 million units, more than 700,000 of which are sold in this country. That first-year sales force of eight has grown to 4500, and there are now 38 Honda models sold in America instead of the original six. And then there are the six scooter models and a 12-model ATV lineup, plus lawnmowers, power generators, outboard boat motors, earth tillers and a group of automobiles that Americans now buy to the tune of 400,000 a year.

As impressive as those figures are, perhaps the best way to judge the company’s growth is to look at its sales brochures and owners manuals from those early years. Today’s Honda literature is slickly done, carefully worded and rife with all sorts of warnings that are mandated by the company’s productliability lawyers.

Such was not always the case.

Witness the photo of an early Honda Dream brochure cover showing test riders strung out behind the bikes in an obvious effort to wring every last once of speed out of their valance-fendered, square-shocked machines.

Not only was this kind of riding behavior shown on brochure covers, but the 1959 CB92 Benly 125 Super Sport owner’s manual actually recommended it under the heading “Highest Speed Test by Flying Posture.”

There is a caution that a straight stretch of at least 600 feet be used for the speed run because “less than this, fallacy is apt to occur.”

Of course, top-speed runs weren’t the only things the Benly was good for. According to the manual, this street bike could be used in “motorcross” competition or “dart” (dirt?) races as weil. The manual’s description of these races? “The motorcross race which requires a very variable and high technique and the dart race which the size of ground and road condition affect the result greatly have many common points.” One of those many common points, apparently, was that the Benly needed a handlebar that was an “up type, its shape should be such as will stand up with slip or side skipping.”

Despite the references to racing, most Benly owners were happy to keep their bikes on public roads, because as the preface to the manual stated, the Benly “keenly responds to modern youth’s demand for speed that will become part of your body and

enrich your everyday life.” In the manual’s jargon even a dead battery could be an enriching experience. “In case the battery has discharged,” the text advised, “shift the gear into second or third and make a push-andrun start. It’s a fun, too, anyway.” Indeed.

Judging by those past statements it’s easy to see that Honda has hired moreproficient translators since the days of the Benly, Dream and Super Cub. And its bikes have progressed none too badly, either. The next question is: If Honda’s silver anniversary brings us into the age of Interceptors, Aspencades and Shadows, what can we expect when the company’s golden anniversary rolls around?

Home for the aged

S ay what you want about the British, but one thing’s for certain: They love their motorcycles. It should come as no surprise, then, to find out that England now has a shrine to honor all its past motorcycling triumphs, if you’ll pardon the pun.

Officially called the National Motorcycle Museum, the facility will house about 1000 examples of British two-wheel ingenuity when construction at the eight-acre site just outside of Birmingham is complete in 1988. The first phase of the museum—four exhibit halls containing 400 fully restored bikes—is scheduled to open this month.

Certainly, finding bikes to stock the display halls wasn’t a problem. Before the onslaught of Oriental machines in the Sixties, England was the world’s largest producer of motorcycles. Some experts estimate that more than 500 different makers once sold bikes to the British public. The museum currently has about 560 machines (representing 110 companies) in various stages of restoration, the oldest being an 1898 Humber, the latest a 1977 Jubilee-edition Triumph Bonneville.

Locating motorcyles for display might not have been much of a problem, but acquiring the funds to erect the $2 million complex has been, and still is. So far, money has been raised through donations, raffles and grants from various British government agencies, but museum officials are hoping that British-bike lovers world-wide will also donate to the cause, as the U.S. Norton Owners Association did recently with a $1000 check.

For more information about donating to the National Motorcycle Museum, write 86 Henwood Lane, Catherine de Barnes, Solihull, West Midlands, England B91 2TH.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Cycle World Editorial

Cycle World EditorialOf Myths And Mystiques

November 1984 By Paul Dean -

Cycle World Letters

Cycle World LettersCycle World Letters

November 1984 -

Special Section

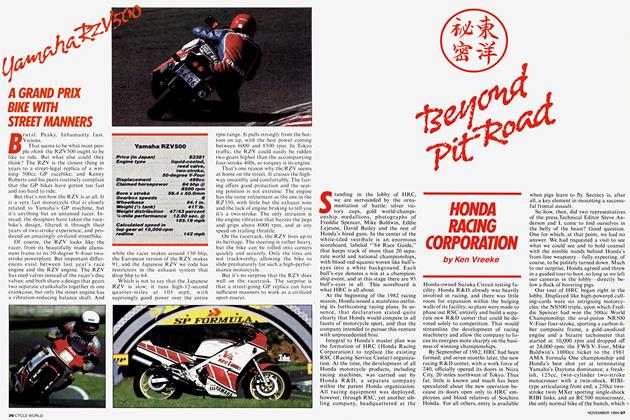

Special SectionBeyond Pit Road

November 1984 By Ken Vreeke -

Special Section

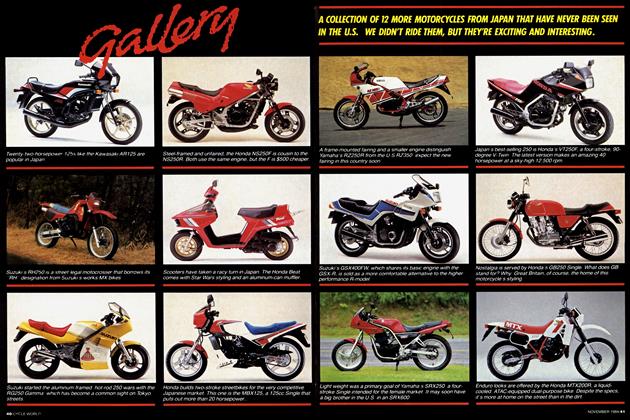

Special SectionGallery

November 1984 -

Special Section

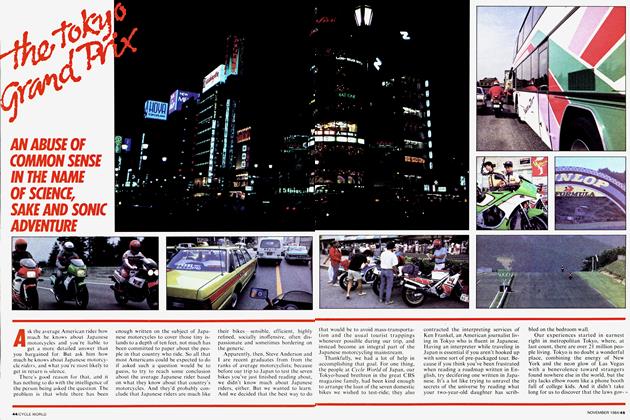

Special SectionThe Tokyo Grand Prix

November 1984 -

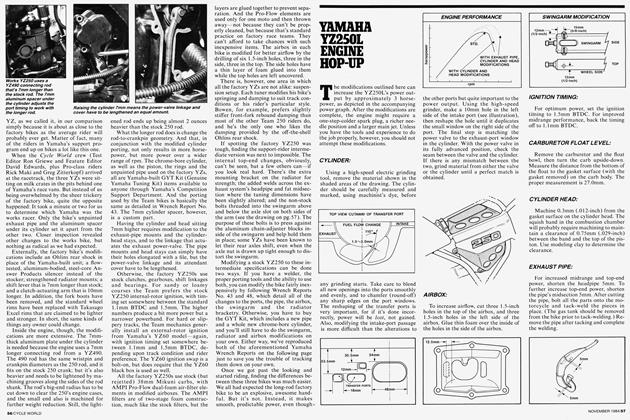

Yamaha Yz250l Engine Hop-Up

November 1984