Of Myths and Mystiques

CYCLE WORLD EDITORIAL

PAUL DEAN

Be careful as you flip through the next few pages. There’s a full-scale war being waged in the Letters column of this issue, and you might have to dodge a few verbal bombs as you pass by.

What the combatants in this War of

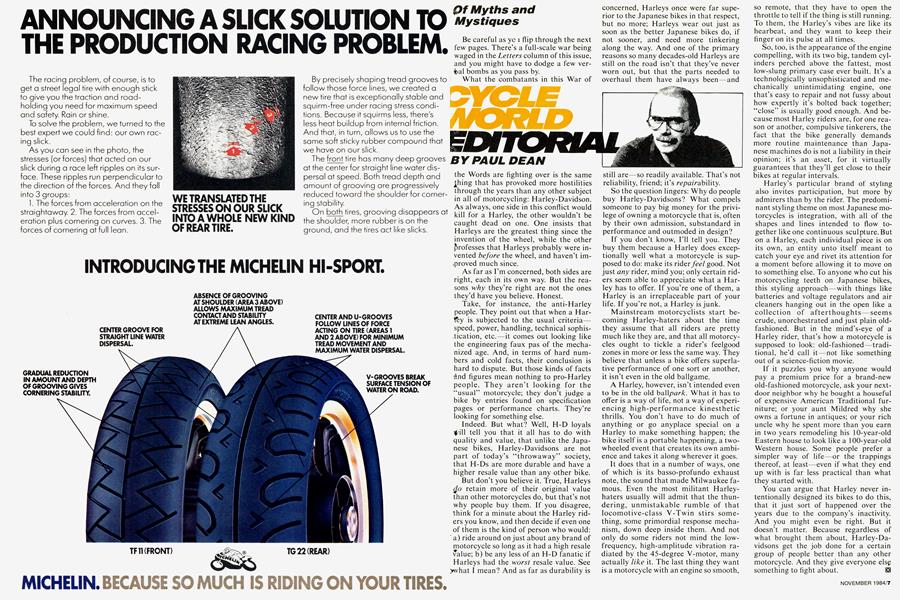

the Words are fighting over is the same thing that has provoked more hostilities through the years than any other subject in all of motorcycling: Harley-Davidson. As always, one side in this conflict would kill for a Harley, the other wouldn’t be caught dead on one. One insists that Harleys are the greatest thing since the invention of the wheel, while the other professes that Harleys probably were invented before the wheel, and haven’t improved much since.

As far as I’m concerned, both sides are right, each in its own way. But the reasons why they’re right are not the ones they’d have you believe. Honest.

Take, for instance, the anti-Harley people. They point out that when a Har’fèy is subjected to the usual criteria— speed, power, handling, technical sophistication, etc.—it comes out looking like the engineering faux pas of the mechanized age. And, in terms of hard numbers and cold facts, their conclusion is hard to dispute. But those kinds of facts ánd figures mean nothing to pro-Harley people. They aren’t looking for the “usual” motorcycle; they don’t judge a bike by entries found on specification pages or performance charts. They’re looking for something else.

Indeed. But what? Well, H-D loyals ’I'ill tell you that it all has to do with quality and value, that unlike the Japanese bikes, Harley-Davidsons are not part of today’s “throwaway” society, that H-Ds are more durable and have a higher resale value than any other bike.

But don’t you believe it. True, Harleys cio retain more of their original value than other motorcycles do, but that’s not why people buy them. If you disagree, think for a minute about the Harley riders you know, and then decide if even one of them is the kind of person who would: a) ride around on just about any brand of motorcycle so long as it had a high resale value; b) be any less of an H-D fanatic if Harleys had the worst resale value. See >what I mean? And as far as durability is concerned, Harleys once were far superior to the Japanese bikes in that respect, but no more; Harleys wear out just as soon as the better Japanese bikes do, if not sooner, and need more tinkering along the way. And one of the primary reasons so many decades-old Harleys are still on the road isn’t that they’ve never worn out, but that the parts needed to overhaul them have always been—and

still are—so readily available. That’s not reliability, friend; it’s repairabiWly.

So the question lingers: Why do people buy Harley-Davidsons? What compels someone to pay big money for the privilege of owning a motorcycle that is, often by their own admission, substandard in performance and outmoded in design?

If you don’t know, I’ll tell you. They buy them because a Harley does exceptionally well what a motorcycle is supposed to do: make its rider feel good. Not just any rider, mind you; only certain riders seem able to appreciate what a Harley has to offer. If you’re one of them, a Harley is an irreplaceable part of your life. If you’re not, a Harley is junk.

Mainstream motorcyclists start becoming Harley-haters about the time they assume that all riders are pretty much like they are, and that all motorcycles ought to tickle a rider’s feelgood zones in more or less the same way. They believe that unless a bike offers superlative performance of one sort or another, it isn’t even in the old ballgame.

A Harley, however, isn’t intended even to be in the old ball park. What it has to offer is a way of life, not a way of experiencing high-performance kinesthetic thrills. You don’t have to do much of anything or go anyplace special on a Harley to make something happen; the bike itself is a portable happening, a twowheeled event that creates its own ambience and takes it along wherever it goes.

It does that in a number of ways, one of which is its basso-profundo exhaust note, the sound that made Milwaukee famous. Even the most militant Harleyhaters usually will admit that the thundering, unmistakable rumble of that locomotive-class V-Twin stirs something, some primordial response mechanism, down deep inside them. And not only do some riders not mind the lowfrequency, high-amplitude vibration radiated by the 45-degree V-motor, many actually like it. The last thing they want is a motorcycle with an engine so smooth, so remote, that they have to open the throttle to tell if the thing is still running. To them, the Harley’s vibes are like its hearbeat, and they want to keep their finger on its pulse at all times.

So, too, is the appearance of the engine compelling, with its two big, tandem cylinders perched above the fattest, most low-slung primary case ever built. It’s a technologically unsophisticated and mechanically unintimidating engine, one that’s easy to repair and not fussy about how expertly it’s bolted back together; “close” is usually good enough. And because most Harley riders are, for one reason or another, compulsive tinkerers, the fact that the bike generally demands more routine maintenance than Japanese machines do is not a liability in their opinion; it’s an asset, for it virtually guarantees that they’ll get close to their bikes at regular intervals.

Harley’s particular brand of styling also invites participation, but more by admirers than by the rider. The predominant styling theme on most Japanese motorcycles is integration, with all of the shapes and lines intended to flow together like one continuous sculpture. But on a Harley, each individual piece is on its own, an entity unto itself meant to catch your eye and rivet its attention for a moment before allowing it to move on to something else. To anyone who cut his motorcycling teeth on Japanese bikes, this styling approach—with things like batteries and voltage regulators and air cleaners hanging out in the open like a collection of afterthoughts—seems crude, unorchestrated and just plain oldfashioned. But in the mind’s-eye of a Harley rider, that’s how a motorcycle is supposed to look: old-fashioned—traditional, he’d call it—not like something out of a science-fiction movie.

If it puzzles you why anyone would pay a premium price for a brand-new old-fashioned motorcycle, ask your nextdoor neighbor why he bought a houseful of expensive American Traditional furniture; or your aunt Mildred why she owns a fortune in antiques; or your rich uncle why he spent more than you earn in two years remodeling his 10-year-old Eastern house to look like a 100-year-old Western house. Some people prefer a simpler way of life—or the trappings thereof, at least—even if what they end up with is far less practical than what they started with.

You can argue that Harley never intentionally designed its bikes to do this, that it just sort of happened over the years due to the company’s inactivity. And you might even be right. But it doesn’t matter. Because regardless of what brought them about, Harley-Davidsons get the job done for a certain group of people better than any other motorcycle. And they give everyone elsç something to fight about.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Cycle World Letters

Cycle World LettersCycle World Letters

November 1984 -

Cycle World Roundup

Cycle World RoundupThe 15 Million Dollar Motorcycle

November 1984 By David Edwards -

Special Section

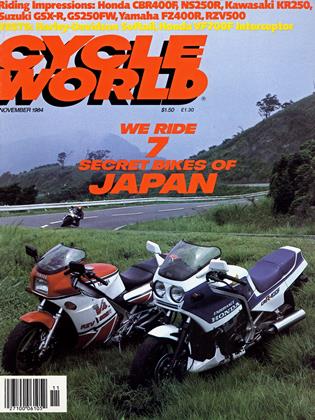

Special SectionBeyond Pit Road

November 1984 By Ken Vreeke -

Special Section

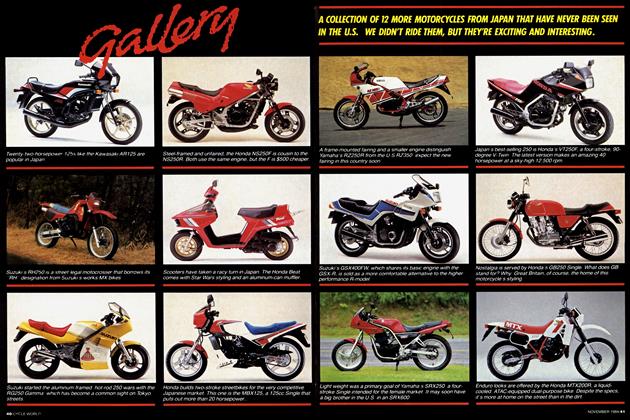

Special SectionGallery

November 1984 -

Special Section

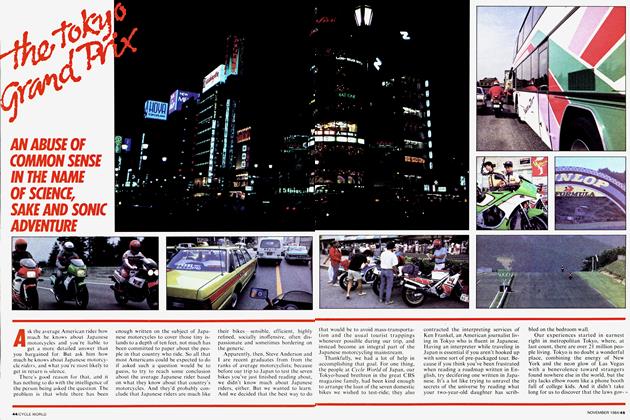

Special SectionThe Tokyo Grand Prix

November 1984 -

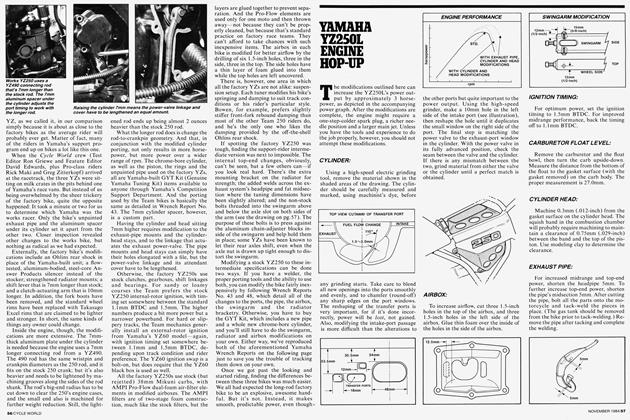

Yamaha Yz250l Engine Hop-Up

November 1984