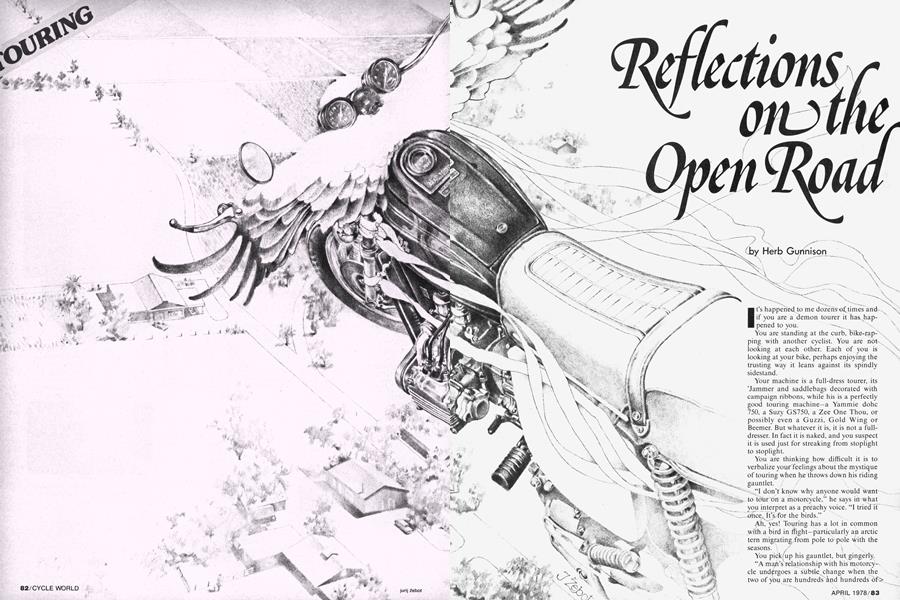

TOURING

Reflections on the Open Road

Herb Gunnison

It's happened to me dozens of.times and if you are a demon tourer it has happened to you.

You are standing at the curb, hike-rappin« with another cyclist. You are not . looking at each other. Each of you is looking at your bike, perhaps enjoying the trusting way it leans against its spindly sidestand.

Your machine is a full-dress tourer, its 'Jammer and saddlebags decorated with campaign ribbons, while his is a perfectly good touring machine—a Yammie dohc 750, a Suzy GS750, a Zee One Thou, or possibly even a Guzzi, Gold Wing or Beemer. But whatever it is, it is not a fulldresser. In fact it is naked, and you suspect it is used just for streaking from stoplight to stoplight.

You are thinking how difficult it is to verbalize your feelings about the mystique of touring when he throws down his riding gauntlet.

"I don't knpw why anyone would want to tour on a motorcycle," he says in what you interpret as a preachy voice. "I tried it ít^for the birds."

Touring has a lot in common with a bird in flight—particularly an arctic tern migrating from pole to pole with the seasons. I

You pick up his gauntlet, but gingerly. "A mail's"relationship with his motorcycle undergoes a subtle change when the two of you are hundreds ánd hundreds of> miles from home," you begin.

The guy seems interested.

"Let me give you an example," you continue, mentally shifting up.

You describe the feeling you get at the end of a 600-mile day when, figuring you've earned a hot bath and some magic fingers in your mattress, you call it quits in front of a motel office. You explain how those 600 miles have cut you off from the routine associations which have given you a sense of security for the past 50 weeks. Now you and your bike are on your own and if either lets the other down there's going to be hell to pay.

Why?

Well, because unlike the working weeks of your life, you can't put a price on your touring vacation. If you get stranded now the whole year would be shot.

However, your bike hasn't missed a lick. You have strong feelings about that, partly based on respect for the machinery and partly indefinable, but indefinable only because you are self-conscious about applying the word "gratitude" to an inanimate object.

Inanimate?

How can anything that's just carried you 600 miles on its back be called "inanimate?" You decide, therefore, that it is reasonable to feel grateful.

You apologize to your friend for freeassociating.

Then you explain that you are a long way from home and that if you are not exactly in an Arab-camel-oasis situation it is only, perhaps, because at the moment you are in Oshkosh instead of Barstow—or 600 miles southeast of Bant Suwayf.

Your companion wrinkles his nose as if a camel had ambled up and was spreading his hind legs. His interest is waning, but you doggedly continue, searching for words which will reveal the mystique.

You tell him how you come out of the motel office, helmet in one hand and room key in the other, and notice that your room is just across the courtyard. You're not about to put your helmet on to ride 100 feet, so you nudge your thigh against the seat until the kickstand snaps up and then shove against the handlebars.

This drill reverses the usual rider-motorcycle relationship. What the motorcycle has been doing for you for 600 miles you now gladly do for the motorcycle for 100 feet. Almost as soon as it begins to roll it is transformed from a lummox to a graceful friend strolling beside you, carrying all your gear in perfect balance, uncomplaining.

You are enjoying a quiet moment with your bike.

Then you describe how you turn the handlebars and lead the bike around a puddle in the courtyard so it won't have to spend the night with wet tires, smiling to yourself because back in the rational world where you live, and especially where you work, such a fantasy would be the most unheard of nonsense anyone ever heard of.

Your new-found friend is looking hard at his bike and you know he is considering making a run for it, but you keep right on talking.

You tell him that when the cycle rolls up in front of your room you actually have to apply the front brake to keep it from running into the curb. It stops as easily as it rolled. Such willingness, such cooperation, even after you had killed its engine, makes you feel something stronger than gratitude. Now you are aware of an emotion curiously close to love for your bike—that is, love in the sense of animate objects sharing burdens, of helping one another. As it is with love, you believe you are getting the best of the bargain, and at 600 miles to 100 feet you know you have established a workable, indeed a classic love-efíort ratio.

Then you describe how you turn the handlebars and lead the bike around a puddle in the courtyard so it won't have to spend the night with wet tires.

Your new-lost friend rolls his eyes skyward and mouths an inaudible "hoo boy!" Then he takes out his Kawasaki key and rubs it impatiently between his thumb and forefinger.

"Look. You've lost me," he says without smiling. "I once rode all the way from Louisville to Cincinnati and back in one day—that's over 200 miles—and got caught in a thunderstorm and spent a miserable hour under a viaduct. Naw, I like action. Touring's for the birds."

You blew it. Everything you said went in one ear and got pounded to gibberish between the anvil and the hammer.

The Z-l roars to life. As the stranger clutches into second you see five inches of air between the front skin and the pavement. You grudgingly admit he has made his point far more powerfully than you have.

Sitting there, all the arguments you might have used come to mind. It's an old story: Where were they when you needed them? You know the non-cyclists and even the non-touring cyclists do not understand how you feel. Perhaps this exclusiveness, this isolation from everyday enthusiasms, is part of the mystique. (You're secretly thankful all motorcyclists don't tour.)

Perhaps. Perhaps.

But one thing you know for damn sure is that riding from Louisville to Cincinnati is not a fair test. There is no such thing as instant touring. In fact our instant pleasure and instant comfort culture is often what the tourer is escaping from. The dyed-inhis-leathers tourer says thanks but no thanks: For once let me do it my way. Let me find my own nourishment, my own entertainment, instead of forfeiting my stomach and my psyche to the Kraft Foods conglomerate.

You daydream about a real back road where there are no stoplights.

But soon you are back with your touring obsession. Round tripping from Louisville to Cincinnati—now that is for the birds. A 200-mile "tour" requires little effort, no preparation and no commitment. Since you would be traveling through familiar landscapes there would be no new horizons. Moreover, the road is all interstate and every tour should include back roads as a matter of principle. Such a sampling of the mystique is over almost before it starts. Because your trip ends where it started, you will never know how it feels to have someone in Key West look at your license plate and exclaim, "Did you come all the way from British Columbia on . . . that?"

"I sure did, m'am."

... Or how it feels to look at your Gold Wing with new eyes, sharing her astonishment.

The hell with it. You look both ways and

go-

In retrospect you figure your front skin was a good 10 inches above the deck when you flashed under the signal.

And in this aggressive stunt—when you almost lost it—you found, perhaps, the first truth about the touring mystique.

It is powerful.

It is just as powerful as the compulsion that makes a hillclimber hold it on and hold on when he knows the bump ahead is going to loop the whole shebang.

It is just as intense as the drive that makes an enduro rider jam his boot between his wildly spinning knobby and a slick riverbank root, gladly sacrificing his foot to the God of Traction just so he can zero the next moment of truth.

If you doubt the touring motivation is this powerful, try talking a friend out of his tour the evening before he is due to leave, when his bike is all packed, tuned, waxed and parked in his garage with the front wheel pointing toward Nirvana. Offer him $1000 if he will take his car instead. He will laugh. If you can convince him you're serious about the thou, it might be a nervous laugh, but it will still be one of your basic laughs. That's powerful.

On the other hand the non-touring road rider would probably call off his trip across town for $10. He is practical and would rather be $10 richer than $1000 poorer. He is comparable to the hillclimber who shuts off and the enduro rider who waits for a following rider to come along and give him a push. Nothing wrong with that unless you have a low opinion of common sense . . .

Maybe that's what sets the tourer apart. He doesn't want to be, or claim to be, rational. He has mastered the irrational art of traveling the right way down a one-way street that is going the wrong way. He can break the law of conformity so skillfully that even the fuzz has no idea what's coming down. Common sense just doesn't turn him on: As he sees it, the world is overloaded with common sense. The tourer with a faraway look behind his goggles thumbs his nose at common, reasonable, no problem, no effort transportation—the Greyhound, the automobile, the jetliner—and at reasonable destinationsChicago, L.A., New York. He wants to go to Hull, Nebraska, or Gunnison, Colorado, or, if his vacation was long enough, perhaps to Zanzibar.

continued on page 126

continued from page 84

The world of ideas can never quite pin down the uncommon experience of the touring rider. Consider for example the first idea that comes to mind when the word "mystique" is applied to extraordinary human endeavors. It is George L. Mallory's famous reason for climbing a mountain; "Because it is there." I confess I have never really understood that remark. After all, caves are "there." Why didn't he crawl down into a cave? And motorcycles are everywhere—so why didn't he get involved with bikes?

Doesn't make sense, does it?

Part of the mystique has to do with pride of ownership. A Gold Wing owner would probably rather eat worms than ride a BMW, and a BMW owner would surely rather eat a robot whale than ride a Gold Wing. Both these marques probably make the Ducati buff sick to his stomach. It's a ridiculous and comic affair, bad-mouthing all these great bikes, and I'm getting a little queasy just writing about it. Still, it will probably never end. Take the Harley rider, for example, cruising in a private world with the oldest mystique of all, one that goes back to thundering cut-outs and dirt roads; a mystique that I have enjoyed on 16 different models beginning with a 1928 JD. The Harley mystique is perhaps the most difficult of all to define, because it is hoary with age. Then there's the Guzzi. The Guzzi owner is a special case. All he wants is to be counted in the fraternity of tourers, but he faces unfortunate odds because his superb machine rarely gets good publicity, all because of a silly air cleaner snafu. And, paradoxically, in my humble opinion this most beautifully styled bike of all suffers from the most unimaginative ads in the industry.

But despite these intense loyalties, so magnificently opinionated, most tourers are equally unqualified in their enthusiasm for their common sport. They share a determination to set up their bikes for the job they were created for, to gloss over the rough spots and, when they occur, to ignore their brand preferences and help each other out.

The true tourer is always looking for a helmet on the shoulder.

And the true tourer knows in his heart that if the company which made the bike he is riding went out of business he would transfer his loyalty, intact, to a marque he now despises.

This attitude doesn't make sense, but it has a vital quality sense often lacks—an overwhelming enthusiasm—which is part of the mystique separating motorcyclists from ordinary travelers.

Again and again in this discussion we are confronted with an indefinable spirit. Possibly we have been on the wrong track trying to reason it out. It might be better if I described three episodes from my touring life and let you draw your own conclusions. Let's do that because in the final analysis the mystique is a matter of the intuitive understanding of supranatural experiences. All motorcyclists may not agree with or fully understand what I am about to relate, but perhaps it is better that way: We don't want everyone to suddenly start touring, now do we? Besides, you unquestionably have had experiences that I could not relate to. The important thing is that each of us reacts to the phenomenon of twowheeled travel in terms of our own complex lifestyles.

Common sense just doesn't turn him on: As he sees it, the world is overloaded with eommon sense.

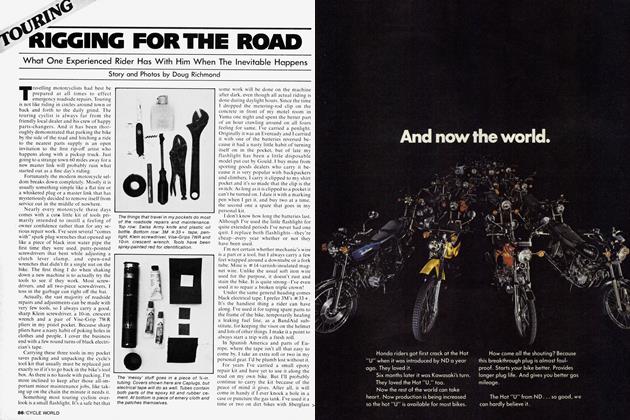

It is six a.m. Weather is coolish.

I put my lightweight mittens on. Put my helmet on. Take my mittens off. Fasten the helmet strap in the D rings. Put my mittens on. Take my right mitten off and put it on the starboard saddlebag. Fish in the right slash pocket of my leathers for ignition key. Take my left mitten off and put it on starboard saddlebag. Fish the ignition key out of the left slash pocket of my leathers. I climb aboard, fire 'er up, and ride off. A half-mile later I ride back and pick up my mittens. Put mittens on.

My day has officially begun.

This is, if you will excuse the expression, an "oblique mystique." That is because if I had been in an automobile I wouldn't have had all that fuss, but there wouldn't have been any mystique, either. The auto-convenience would therefore have been offset by the fact that I would have had to struggle through an unofficial day.

The difference between an official and an unofficial day is important.

An official day is one where, when you tell someone what happened to you, the other person says "Wow! I know what you mean. That's happened to me!" If you're lucky, he may even smile knowingly. Then you feel warm inside.

An unofficial day is one where, when you tell someone what happened—like, you put your key in the car's ignition switch and turned on the heater—the other person says "So what?" Then you feel cold inside.

Contrary to what most people think, tourers are rarely cold, even in cold weather. This is only partly because of the fact that they are electrified by a direct line from their bikes.

These remarks are not prejudiced. I will admit, for example, that occasionally their hands might get cold.

But only for as long as it takes to ride a half-mile.

If you can't identify with this episode, if you have difficulty relating to mittens (some people just can't relate to mittens) then substitute some other inconvenience, such as a severe crosswind, a thunderhead on the horizon, sudden late night temperature drops, and/or eight-hour-rain days.

If you can relate to and actually enjoy such hazards instead of letting them freak you out, then you are definitely an official tourer.

Fortunately there is another side to this coin.

Time: next summer. Weather: perfect.

I am on a back road. I had forgotten the joy of riding a lonely twister where a cyclist has the choice to ride on the left side of the road if it feels smoother and is safe, or in the center if he is so inclined, where there are no white lines, yellow lines, or don'tdo-this-or-that lines. I am on a back road where there are no advertisements except nature's perpetual self-advertisement, where there are no towns, no stoplights, and above all no people expecting me to act in a certain way. I am on a back road where the only thing that prevents me from taking a leak in the center of it is concern for my boots and where, if my luck holds, another Gold Wing-mounted genius with the same brilliant idea will flash by with a startled laugh and a belated twist-around wave. I am on a real back road which connects the illusion I started from with the illusion to which I must return. I am superbly alive and I know the mystique of touring lurks just around the curve we are leaning into.

I am you.

Sometimes the coin balances precariously on edge.

At the tag end of a colorful late fall afternoon in 1971 my Moto Guzzi Ambassador and I were approaching the Somerset exchange on the Pennsylvania Turnpike. Our seemingly endless and glorious 600-mile day was drawing to a close. What was left of the sun was directly behind and our shadow was outdistancing us. The Guzzi was passing the time humming to itself while I was admiring the shadowbike's suspension: It was ghosting over the frost heaves and tar strips without so much as a flicker.

I was faced with one of those enjoyable, you-can't-lose decisions touring riders often make. Should I stop in Somerset for supper and then ride to Harrisburg in the refreshing coolness of early night, or should 1 keep going and soak up the shortlived, earthy melancholy of a great day waning imperceptibly into the prospect of a memorable evening?

continued on page 150

continued from page 126

Although I was hungry, stopping for food seemed too time consuming, too rational for my endless-day mood. Besides, there is more than one kind of hunger.

This decision should have been spontaneous, but I was curious about the time. The older I get the more imagination it takes to keep moving faster than time, but since 600 miles in the saddle had reduced me to an extremely mellow but unimaginative lump. I decided to check my watch.

A Gold Wing owner would probably rather eat worms than ride a BMW, and a BMW owner would surely rather eat a robot whale than ride a Gold Wing.

In the left slash pocket of my jeans I had one of those nickel-plated dollar watches which at that time sold for $3.95. Like many enduro riders I used it for timekeeping because it had a big dial and was rugged and cheap. It had many hard enduro miles under its case as well as great sentimental value. There was no way I could put a price on it.

As I stood on the pegs to reach into my pocket I remember thinking I had to be careful because I was moving at 75 miles per hour and the watch didn't have a lanyard to catch it if it fell.

As I brought it out of my pocket it— unaccountably—slipped out of my hand.

Instinctively I jerked my left boot upward to cushion its fall—as a condemned man might instinctively walk around a puddle in a wet courtyard on his way to the scaffold.

The watch hit my upcoming boot and bounced into the air.

It glistened in the sun as it sailed along beside the Guzzi.

At this point in time it was a perfectly functioning watch, correct within an unimportant minute or so, with its mainspring energy tight, its escapement ticking precisely to and fro, each gear jogging according to its size and function and in general paying more attention to the universal laws of physics than the headstrong Guzzi was to the local laws of speed.

You couldn't call this quartzless, digitless timepiece a miracle of technology, but there was no denying it was in a miraculous situation, this piece of time suspended for an instant six inches from the Guzzi's left valve cover and two feet from the whizzing 'pike—idly ticking away, ticking away, as if it had all the time in the world.

continued on page 154

continued from page 150

Striking the State of Pennsylvania precisely on edge, my watch bounced three feet above the concrete, its nickel-plating again flashing in the sun.

It was now spinning like the Guzzi's wheels but unlike the Guzzi it was traveling way over its head.

At the second jolt the crystal spun off glinting everywhichway.

Another ricochet and the back popped off and whirled away in a shower of sparks.

Then the face went, white as a sheet.

I twisted around in the saddle; if I had been tailgating a semi and its brake lights had just flashed on it wouldn't have mattered.

Striking the State of Pennsylvania precisely on edge, my watch bounced three feet above the concrete, its nickel-plating again flashing in the sun.

This I had to see.

To my knowledge the watch never stopped bouncing. Its reflections in the evening sun changed from glassy to nickel bright to white and finally to golden as the brass gears, cogs, wheels and backing plates spilled out on the turnpike at speed. With each diminishing skip the watch got smaller and smaller until suddenly all its remaining parts dissolved in thin air without a trace.

It was beautiful.

Now I ask you, where but at the end of a priceless day of touring, on one of his alltime favorite bikes, could a guy have so damn much fun with a cheap watch?

Nothing in my touring life has brought me closer to the elusive touring mystique than this experience, and yet even this one missed by a hair.

Some day I'm going to take my grandfather's gold watch out of its velvet-lined case, wind it carefully, set it, and then slip it into the slash pocket of my jeans.

Then the Guzzi and I will take off for Pennsylvania . . .

But wait!

Perhaps you can tell me what the mystique is all about, and thus preserve my valuable family timepiece.

We're bound to meet somewhere on the road this summer.

We might even share a two-bit time-slot by a parking meter in Zanzibar.