CYCLE WORLD ROUND-UP

THE EPA IS LISTENING

One of our most common laments in testing today’s motorcycles is the absence of an exhaust note. We were particularly fretful over this lack in the Honda GL1000 (July), which is about as silent a mount as there is in cycledom, and we were elated by the whiskey tenor of Yamaha’s XS7502D shaft drive Triple (April). For anyone conditioned by years of British Twins and Harley Davidsons to equate motorcycling with a certain joyful burble of power, the well-oiled whirring of a Japanese Four fails to satisfy the soul.

However, the Environmental Protection Agency has proposed a new batch of noise regs that may make the comparison of exhaust notes a strictly retrospective discipline. Although the EPA estimates that motorcycles constitute only 1.5 percent of the traffic stream, the agency has attuned its unsleeping ear to the sounds emitted by two-wheeled machinery. As a consequence of this attention, it seems likely the EPA will impose a mandatory decibel limit for new street and off-road bikes, exemptions being made for pure competition machines and those with 50 cc or smaller engines. There will also be regs governing aftermarket exhaust systems to bring them into line with those provided by the motorcycle manufacturers.

In appointing itself broker for national health and welfare benefits concerning motorcycle noise—the agency even claims to be intervening on behalf of riders, who, as far as we know, almost never complain on this score—the EPA is on the point of imposing a diminishing scale of dB numbers that are certain to make big waves through cycledom, for manufacturers and consumers alike. The initial levels, proposed for 1979 and 1980, are essentially commensurate with most new bikes on the market today, give or take a dB or two: 83 dB for street machines, 86 for dirt bikes. However, some 10 years down the road EPA expects to decrease these numbers to 75 and 78.

This isn’t even remotely as simple as it probably seems to the non-motorcycling legislative visionaries who originally inspired it. The dB scale involves a series of geometric progressions, and going from, say 75 to 83 isn’t at all like adding Sacramento to an L.A.-San Francisco itinerary: It’s like adding Fairbanks. Going down the scale involves the same sort of quantum leaps.

In floating some trial balloon-style literature on the proposed regulations, EPA officials blithely admitted the low numbers would have the following affects on motorcyclists: “1) Motorcycle purchase prices will increase ... 2) Performance will be somewhat diminished, including reduced power, increased weight, and certain affects on handling ... 3) Some motorcycles may require liquid cooling to achieve regulated noise levels ... 4) Certain models of motorcycles may be unable to meet noise standards and will therefore no longer be available.”

This last has an Orwellian ring to it that’s particularly ominous. The EPA seems cheerfully willing to see some manufacturers simply disappear if meeting an arbitrary set of noise standards isn’t economically feasible for them. It also seems that a new wave of ponderous watercooled, shaft-drive heavyweights—uneconomical, boring, but dead silent—could become the industry standard.

If the regs went into effect today, most new bikes would need some work to be street legal. The language of the regulations sets 83 dB as the standard, but stipulates further that “manufacturers will have to design to 3 dB below these levels and produce to 2 dB below these levels to allow for production variations.”

The GL1000, which tips the meter at about 78 or 79 dB, would be OK as is, but something like the Suzuki GS750, which hits about 82 dB, would need attention. Undoubtedly, the Yamaha’s whiskey tenor would be legal only in the shower.

John Walsh, Suzuki’s resident decibel genius, says there’s almost as much concern in the industry with noise testing procedure as with the numbers themselves. Without going into technical detail, the test procedure currently under consideration-involving full acceleration in bottom gear—will probably penalize big bikes. Excessively.

“Depending on the lead time involved, almost everybody should be able to handle the first stage,” says Walsh. “But it’s generally recognized that reducing the sound level below 83 is frivolous—there are so many other sources producing much higher levels. And for the aftermarket guys—well, at the very least it would create an enormous administrative burden.”

A member of the California Highway Patrol’s engineering staff sees 80 dB, one of the EPA’s later goals, as within reasonable reach, but feels further reduction would be overkill.

“I’d certainly like to argue with them on that 75 number,” he says. “Most of the noise problems connected with motorcycles have nothing to do with new machines—it’s modifications made later. I really don’t see any reason to go down below 80.”

The EPA’s response to these and other anticipated objections is a specious and misleading appeal for the Greater Good: “When combined with regulations to quiet other products contributing to traffic noise (i.e., automobiles, medium and heavy trucks, buses), the motorcycle regulations will reduce the number of people regularly exposed by nearly 60 percent over the next decade.”

All of this sounds very much like the sort of statistical psalm singing that preceded the federally-coerced rash of helmet laws. We certainly favor the voluntary use of helmets by motorcyclists, and we in no way endorse excessive noise—it’s taken long enough for our pastime to climb out of the Dark Ages as it is.

But it’s hard to imagine any ordinary citizen of the realm, rider or no, objecting to any of today’s production bikes because they’re too noisy. It’s like calling Jerry Lewis subtle—doesn’t relate to the facts.

This is another of those motorcycle issues in which our non-response can be interpreted as acquiescence, particularly since the EPA is interested in sampling opinion on its proposals. For a background document on the proposed regs, write: Henry E. Thomas, Director, Standards and Regulation Division (AW-471), U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, Washington, D.C. 20460. Mr. Thomas is also the proper contact for your opinions on this matter.— Tony Swan.

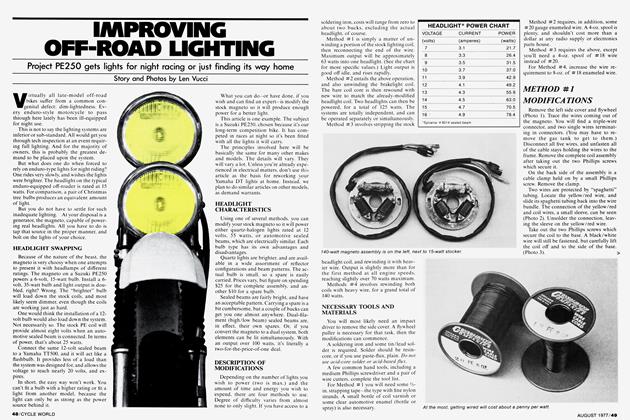

RUSS COLLINS’ DOUBLE HONDA FUNNYBIKE

Russ Collins, who makes motorcycles go straight ahead faster than anyone in the world, is at it again, undaunted by a high speed tumble last year. The latest in the ongoing series of R.C. Engineering drag bikes is this supercharged fuel-injected double Honda fueler, shown here in its first exercise outing at Irwindale Raceway.

The bike’s engines, Honda 750s bored to 1000 cc each, embrace a 371 GMC blower, whose drive, designed by R.C.’s Byron Hines, also powers the Crower fuel pump and port injection system. Operating with a 6.1:1 compression ratio, the twin Hondas start on gas but burn an 80to 90 percent nitromethane mixture on the strip.

The engine package, which extracts as a unit for servicing, sits inside a super-strong Don Long birdcage chassis with an 86.5-in. wheelbase. Front forks are Ceriani, with a Circle Industries fork brace. The double front discs are Airheart/Kosmer.

A B&J two-speed transmission sends power to the big slick at the rear via a 10.5in. Crowerglide clutch and double #50 chain. A special R.C. touch is the bike’s air shifter, pressurized at 400 psi. The shifter is hand controlled; there are no foot controls on the bike, just a pair of pegs set at either end of the rear axle.

Collins, Hines, Long and the rest of the R.C. crew collaborated on the beautifully engineered and constructed beast, which Collins hopes will become the first bike to break the six-second barrier. With some 600 hp propelling the 800-lb. machine, and the experience of the tripleengined bike that preceded it (Collins was first to take a bike inside eight seconds before the triple bit him), R.C. expects the new machine to not only do six-second quarters but hit 200 mph as well. Both these achievements would be consistent with previous R.C. efforts. Since R.C. opened its doors in Gardena, California in 1970, every bike out of the shop, some 15 in all, has set some sort of National Hot Rod Association or American Drag Racing Association record.

However, the opening shot for this particular funnybike was inauspicious enough. Collins managed about a third of a run—just enough to light up the tire and fill the air with the ear-splitting shriek one associates with funnycars and AA fuel dragsters—before the big drive chain began showing signs of old age.

Collins and crew checked the plugs, whose electrodes were burned almost down to the nub, allowed as how they had their beast running just about lean enough, then settled in to wait for a fresh chain, which happened to be en route from the airport.

When this arrived, Collins ran it in with a few spectacular tire lightups at the starting line, then made what he called “a halfpass at full throttle,” shutting off well before the timing lights and staying in first gear throughout. The result; 9.25 seconds at 125 mph, and the conclusion is that the bike shows a marked appetite for drive chains.

“We’re putting some dampeners on the chain,” Collins said later. “We hope that’ll cure it.”

Otherwise, all systems look like go, handling as well as power.

“I couldn’t believe how straight it went,” said Collins. “It’s almost scary. It handles like a baby carriage.”

Stay tuned.

138 MPH BENELLI

Achieving visibility in the superbike marketplace is getting to be an increasingly difficult assignment, given the performance statistics laid down by today’s hot haulers.

Nevertheless, Benelli recently made itself statistically prominent in this fast company by hitting 138 mph with a box-stock 750 Sei at Pocono International Raceway in Pennsylvania. Times were taken on Pocono’s long main straight, and were aided slightly by a sixto seven mph wind. The 138 mph run was the best of five timed shots down the straight. Throwing out the slowest of the efforts, Benelli came up with a 135 mph average for four runs.

Western/Eastern Roadracers’ Association rider John Fuchs handled the driving. Benelli claims there were no modifications to the six-cylinder rocket other than substitution of a 42-tooth rear sprocket for the stock 46-tooth unit. The bike can be ordered with either sprocket.

HUSKY'S 390 AMX DEBUTS

Husqvarna’s much-heralded sequel to the 360 Automatic Enduro, the 390

AMX motocrosser, got its first taste of combat in the 250 National Motocross last spring in Nashville.

Although the automatic had been under development for several years at Husqvarna R&D in Sweden, Husky brass were reportedly taking a do-or-die attitude concerning the 390’s performance in the moto.

They needn’t have worried. With 19year-old Arlo Englund up, the Husky prototype wound up second in two 500-cc support class motos, trailing only Kawasaki works rider Terry Clark’s 400 in both starts.

Englund’s verdict on the automatic: “It works.”

The setup is the same as that used on the 360 Automatic, using a system of automatic clutches actuated by what Husky engineers call “freewheeling devices.” There are no torque converters, a la Honda’s street automatics, or infinitely variable bands, a la Rokon. (See the February, 1976, CYCLE WORLD for a full report on the 360.)

Husqvarna’s marketing plans were still nebulous as we went to press, but Husky product manager Nils Arne Nilsson spoke of a production version of the 390 AMX possibly being “available here sometime in July.”

Meanwhile, Husky plans to campaign Englund’s prototype throughout the rest of the 250 Nationals.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue