SHALL WE GATHER AT THE RIVER?

A Weekend Ride on the Old Spanish Trail, Across the Green Desert Nobody Knows

Allan Girdler

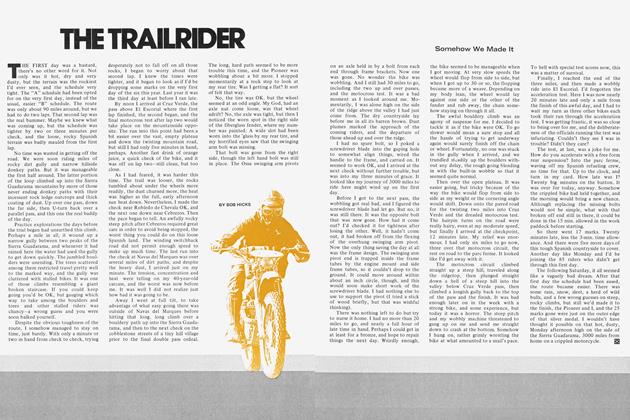

Enterprise. By God, Enterprise! Chuck was riding scout, 50 feet out front as we skirted the edge of the dry lake, crunching across the alkali crust. There was a slight dip with what looked like two feet of mud. Chuck yanked the front wheel up and rolled on full power.

I never saw a bike stop so fast. The Bultaco’s rear wheel touched and ZLUUP. Stone dead in the mud. Kirk and I shut down just on the edge. Dave and Lynn were 100 feet back in the trucks. They saw the trouble in plenty of time.

Four of us couldn’t lift the Bui’s back wheel. We had to haul the front wheel clear, drag the bike through half a circle and tow it out through its own rut.

A mile or two away and as distant as the stars was Old Dad Mountain, gleaming gold in the sunset, as clean and friendly as the surface of the moon. We couldn’t get across the lake. We didn’t know how to get around it.

All the horsepower, knobby tires, fourwheel-drive, CB radios and U.S. Geological Survey maps in the world had us literally bogged in the mud between points A and B. Enterprise. If this is what it was like for us, what was it like 200 years ago with mules, a pair of oxen and a one-ton wagon riding on one-inch steel rims?

What it was like is why we were there.

The journey began almost as a whim. The crew was testing components in a familiar and accessible section of the Mojave Desert. Historian Henry Manney remarked that not far south of where we were one could still find traces of the Old Spanish Trail. The what? Well, the route is even older than the days of Spanish exploration. You could call it the old Government Road or the Pioneer Freeway or Intertribal 1, comes to that.

There are two common views of the Way West. One comes from the fifth grade history books. It shows Dad in shirt sleeves, Mom in a sunbonnet. They're in a Conestoga wagon, looking toward the future as the oxen amble through the green grass. Get in line in Illinois and walk to California or Oregon.

Then there’s the view from your car window between Las Vegas or Phoenix and Los Angeles or San Diego: barren rock, burning sand and scrub brush. Surely no human being could survive a trek across that.

The historical truth lies somewhere between. Crossing the Great American Desert never was a series of picnic lunches. Nor did the pioneers hike 150 miles through the sand and rock.

The key to survival was . . . water. Back 1000 years or so ago the Indians of what's now Arizona, Nevada and eastern California conducted a brisk trading business with the inhabitants of the coast. They discovered, by trial and error, probably that every 20, 30 or 40 miles across the mountains, you’d find some greenery which, if traced, revealed the presence of a spring. When the mountains gave out there was an odd stream, the Mojave River, running roughly east out of the coastal ranges. The Mojave sinks beneath the surface some places and ripples along other places. But if you know where the river is, you can always find water there. The Indians knew it. The first explorers and missionaries and mountain men found out. (The Indians didn’t tell them. In fact they sent the newcomers elsewhere, for reasons which need no explanation.)

Then we invented the iron horse and the horseless carriage and Golden Arches and air conditioning and crossing the desert became four hours of trying to find something good on the radio.

That chance remark became an idea. How was it out there 200 years ago? What would it be like to ride the old trail, along the river bed and from spring to spring?

Could it be done? What about private land and government land and closures of same?

The major problem for off-road motorcycling now is simply finding places to ride. Tracing the route of the Old Spanish Trail would serve as a re-creation of the past, and as a survey in general for any riders curious about finding places to ride.

Step One, the route. The old trail through coastal California is of course gone, swallowed by freeways, housing tracts and military bases.

So we picked a staging place east of the coastal mountains, a way station for the U.S.Army a century ago because it was a deep spot on the Mojave. The name was Camp Cady, now the Cady Ranch.

Owner Ken Wilhelm was not encouraging. “The answer is no,” he wrote. “With help hard to get, we simply don’t have the time to be bothered. We don’t allow any sort of vehicle on the ranch. There’s not a sign of the old trail anywhere on the property.”

Then he warmed to the project. “The best way to locate the old Mojave road is to have a base camp in Afton Canyon. The old road came through the canyon and it’s possible you could camp right on it. I have traveled the old road from one end to the other and always start in Afton Canyon.”

So would we. The United State Department of the Interior, Bureau of Land Management, better known as the BLM, was most helpful. We were surprised, which is probably a comment more on us than on them. A telephone call to the BLM office resulted in a selection of usage maps, multiple colors and all, showing which areas were open, which were closed and which were restricted.

Next came a set of topographic survey maps, sold by the U.S. Geological Survey, Denver, Colo. 80225 or Reston, Va. 22092. The latter come in large scale and complete detail, right down to the names.

Oh, the names. Think of riding past Tough Nut Spring, Mexican Well, Sleeping Beauty, True Blue Mine, Bearclaw Well, Bonanza King Mine and Rainbow Wells.

None of these maps were in scale to each other, but by careful guesswork, we reckoned it could be done. We could legally ride from Afton Canyon clear to the Colorado River, a natural stopping point in our case because government planning has eliminated the seasons. The river is now always deep and one of the few things a mule does better than a motorcycle is swim.

As a pioneer parallel and firsthand hint, in the old days travelers bought maps from experienced guides. Sometimes these maps proved to be, urn, optimistic.

But that comes later. Because we intended to be completely on our own, there was none of this business about being dropped off at the Interstate exit and picked up down the road. Like the old wagon trains, we were reliant only on ourselves. For this we enlisted the crew at Pickup, Van and 4WD, our companion publication, and one as keen on off-road exploration as us. They’d bring trucks, we’d bring bikes. (We gave them the impression that we’d be their scouts, although of course they actually were our supply wagons.)

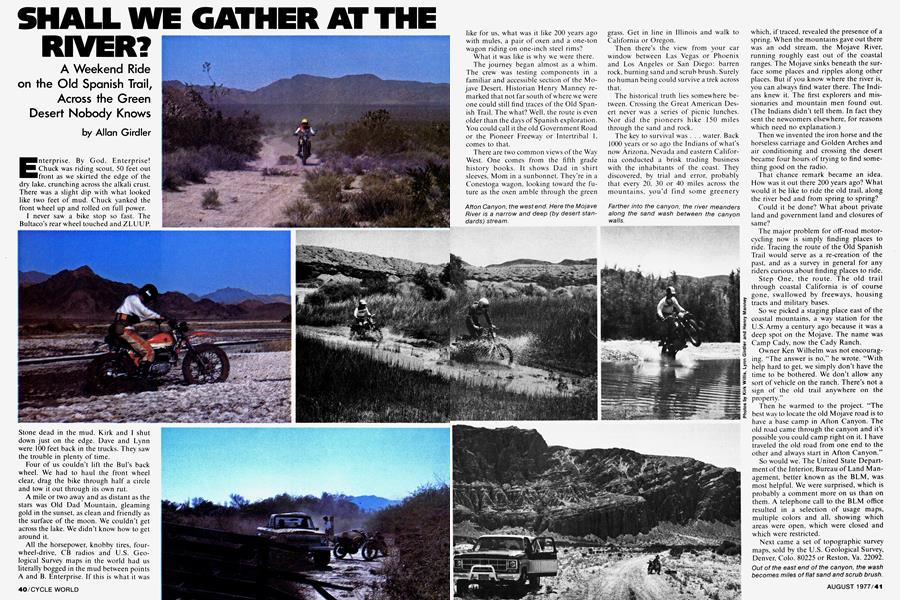

Down Afton Canyon we went one fine sunny Saturday morning. Three quiet and legal motorcycles, two 4WD trucks. We ducked under the railroad tracks and traveled east through the canyon. Red sandstone, green willow trees, sand washes and water sparkling in the sun. Hawks overhead, rabbits in the bushes.

Another pioneer parallel came with two Jeeps going the other way. Each party was going where the other had been, so we stopped and compared notes. Sure, each group said, you can get through there. We just did it.

We were not to see another human being for six hours.

At the end of the canyon the river swings off to the south. The railroad takes most of the space along that route. It also takes all the challenge. Our destination was a spring in the mountains to the east. Between there and us was an almost-dry lake—it had water in the middle. The trail up the west side was closed to protect the wildlife. Going around to the north would be using the paved highway. No fair. There was historical reason to figure the explorers, or some of them anyway, went across the lake.

From the canyon to the edge of the lake was mesquite and blow sand, fine riding. Then we found the abandoned ranch on the maps and the old well on the maps. What we couldn’t find was the road from the old well to the east side of the lake. The BLM map had no trails marked. The topographical map had a trail due east and between the mountains. The county map had a blank.

Blazing across the wilderness, right? The bikes went northeast. Too soft. Due east. Still too soft. There were sand dunes with scrub, hummocks six or so feet high, to the southeast. We ground through, each vehicle locked in first gear and wide-open throttle.

The southeast corner of the lake had the crust mentioned earlier. Away we went, back up to speed and rocketing toward the trail at the foot of the mountain. Off on our left, a forbidding crag. There was a narrow gap between two peaks. Dead ahead an easier passage. The newer road led down the easier way. We followed, then ran north and up a lava flow to the tougher gap.

Then came the mud. No way we’d get across and thank goodness the bike was in front. If it took four men to lift the front of a motorcycle, imagine the problem posed by a mired pickup truck.

More backtracking brought the expedition to a lava flow south of the actual trail. By hitting the dunes full speed we could get through, and we did. Out of the mud and into the boulders, through and across which we crashed and crawled until we climbed a pass and found the old trail leading toward the spring.

Distance, 15 miles. Elapsed time, four hours.

How did the infantry and mules and oxen do it? The history books say there’s a path across the dry (Ha!) lake. We missed it, or the books are wrong.

Either way, it was a good lesson. Those who believe lines on a map mean a trail in real life will find themselves hub deep in mud.

The missionaries did know how to lay trail across the desert floor. We rode the two narrow ruts through the dusk and got to Marl Springs just after dark.

Only Henry had seen the place before. The rest of the party groused. Such a collection of rocks! Where were the showers? The restrooms?

At dawn, all was forgiven. On the side of the hill near a cleft in the rock from which sweet water flowed, was a marker. On this site, exactly 201 years ago to the day, a Franciscan missionary camped on the way east from San Gabriel Mission.

Water. A water shortage in the city is one thing. To be at the only fresh water source within 15 miles is something else. We took

sponge baths. We washed the dinner dishes. We filled canteens and jugs. Jet transports starting their descents on the way to LAX and a freight train whistling across the valley far below only heightened our sense of isolation. We felt a bit sheepish, reverting back in time this way but still, we packed all the water we could carry.

The old trail lay before us, two ruts across the rolling desert, almost due east. Down the gentle slope full speed and across the valley to the next range of hills.

Crossed some pavement, almost against our will, and then we found a wide, graded dirt road. The old route was the best route here, so the path has become a dirt highway. Lovely place, with cliffs and mesas and cedar trees dotting the hillsides. Open range, too, meaning cattle wandering across the road and every so often panicking and running into our path.

Water, again. This was the site of Piute Springs and the remains of Fort Piute.

Desolate. Struggling little bushes and cactus but ride around a cinder cone and hark! Clumps of spring-green willows leading into a narrow canyon.

Desert politics. The spring is the only one for miles around. The Piutes and the Indians before them, whoever they were. located near the spring. When the explorers and missionaries and military arrived, they did likewise.

The fort has crumbled long since. The foundations remain, with a marker telling us that this was a watering stop for the army’s camel patrols before the Civil War.

Odd place for a fort. It’s tucked below the mountain top and around the corner from a view of the open country to the east.

All Fort Piute had was a commanding (just the right word) view of the spring. That’s all the fort needed. Didn’t matter who was doing what out there in the open because those who controlled the water controlled the territory.

Been that way for 1000 years. We found no sign of the Spanish. We did find petroglyphs, flat rocks carved with imaginative figures, done by the original inhabitants.

Once more to the east, straight as a string. We crossed the paved highway, the Nevada/California border and the boundaries of the Mojave Reservation.

We stopped at the crest of a ridge. To our right was a butte topped by what looked like the stone carcass of a whale, remains of a banquet for a race of giants. Ahead was the winding green of the Colorado River. Across the river (although not visible from where we were) the ruins of Fort Mojave bake in the sun.

We had done it. We had seen a more attractive and hospitable desert than pavement-locked travelers would believe exists. We had ridden 140 miles in two days, in conditions ranging from ISDT to flat-outand-hold-your-breath. During two days on the trail we’d seen four other vehicles. We’d committed no trespass, harmed no living thing.

Would this work elsewhere? We see no reason it can’t. Other parts of the country will vary; using a woods bike to duplicate Paul Revere’s ride would be tough. But the New England Trail Riders Association has managed to arrange an impressive collection of cross-country rides, so given the right maps, good manners and proper planning, weekend expeditions should be within the reach of all.

And now, the river. Down off the ridge through a canyon used from prehistoric times and for enduros; white rocks in the white sand had been marked with red and blue paint, the better not to hit them. Best riding of the trip, swooping through the rutted downhills with the wagon tracks as berm, just enough hard rock to keep you on your toes.

The trail led onto the old flood plain and to a levy built by the U.S. Corps of Engineers. When the rest of the expedition arrived, the lead rider was not in sight. There were tire tracks going over the edge. Oh my, he’s flipped out.

Almost. Chuck is a trials rider. He rode down the side of the levy. There parked on the sand was his bike. Next to it, his boots, then his socks, leathers and jersey.

The rider was 20 feet out in the bluegreen water, floating on his back while two days’ worth of dust made coffee-colored wisps downstream.

Speaking for centuries of Indians, traders, soldiers, cowboys, missionaries and pioneer families, he said, “Crossing the dry lake was worth it.’’