Work in Progress

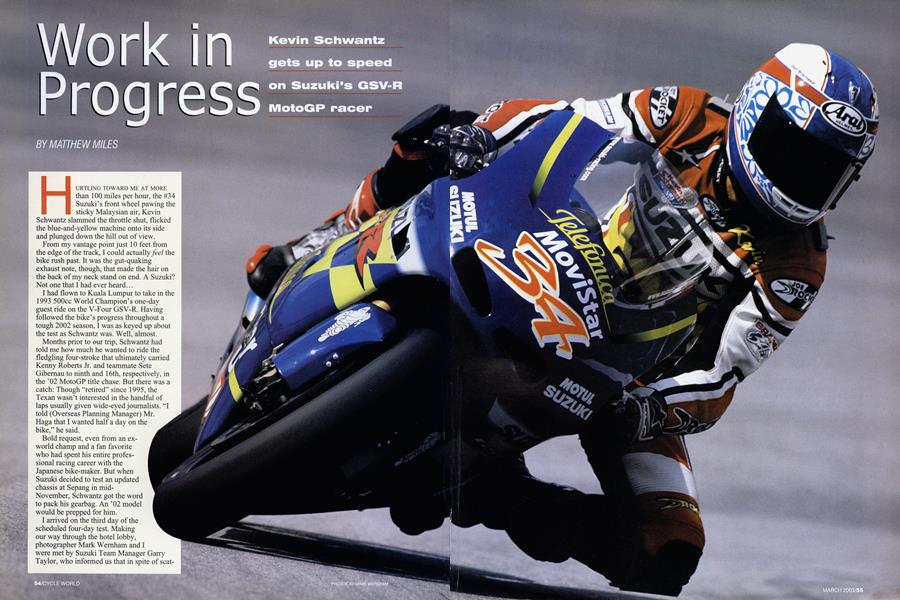

Kevin Schwantz gets up to speed on Suzuki's GSV-R MotoGP racer

MATTHEW MILES

HURTLING TOWARD ME AT MORE than 100 miles per hour, the #34 Suzuki's front wheel pawing the sticky Malaysian air, Kevin Schwantz slammed the throttle shut, flicked the blue-and-yellow machine onto its side and plunged down the hill out of view.

From my vantage point just 10 feet from the edge of the track, I could actually feel the bike rush past. It was the gut-quaking exhaust note, though, that made the hair on the back of my neck stand on end. A Suzuki? Not one that I had ever heard...

I had flown to Kuala Lumpur to take in the 1993 500cc World Champion’s one-day guest ride on the V-Four GSV-R. Having followed the bike’s progress throughout a tough 2002 season, I was as keyed up about the test as Schwantz was. Well, almost.

Months prior to our trip, Schwantz had told me how much he wanted to ride the fledgling four-stroke that ultimately carried Kenny Roberts Jr. and teammate Sete Gibemau to ninth and 16th, respectively, in the ’02 MotoGP title chase. But there was a catch: Though “retired” since 1995, the Texan wasn’t interested in the handful of laps usually given wide-eyed journalists. “I told (Overseas Planning Manager) Mr.

Haga that I wanted half a day on the bike,” he said.

Bold request, even from an exworld champ and a fan favorite who had spent his entire professional racing career with the Japanese bike-maker. But when Suzuki decided to test an updated chassis at Sepang in midNovember, Schwantz got the word to pack his gearbag. An ’02 model would be prepped for him.

I arrived on the third day of the scheduled four-day test. Making our way through the hotel lobby, photographer Mark Wemham and I were met by Suzuki Team Manager Garry Taylor, who informed us that in spite of scattered rainshowers, Roberts Jr. had completed his work and would jet back to the U.S. the next morning. The team’s newest recruit, American teenager John Hopkins, would stay and join Schwantz on-track.

Schwantz woke early the next morning and couldn’t get back to sleep. “All night, I was down the front straightaway, trying to remember this friggin’ place from watching practice and riding around it a couple of times on a scooter,” he said.

So while Wemham snapped statics of the bike, Schwantz and I took a look around the track. The 15-tum, 3.44-mile Sepang Circuit is even more impressive in person than it appears on television. Opened in 1999, the magnificent facility hosts the annual Malaysian Grand Prix, as well as other international motorsports events, including a round of the FIA Formula One World Championship.

Overnight rains left the track wet in many places, including the front straight, where during last October’s GP, Roberts’ GSV-R-code-named XREO-had been clocked at 180 mph, some 10 mph down to the Honda RC211V of ’02 title-winner Valentino Rossi.

As Roberts and Gibemau’s positions in the final points standings suggest, the Suzuki took a pounding last season-and not just on top-end. No surprise, really. At the beginning of the season, the all-new engine-a dohc, 16valve, 990cc, 60-degree V-Four stuffed in a twin-spar aluminum frame dimensionally similar to the old two-stroke RGV500-was just two months old, and shoved into service a full year ahead of schedule. Testing took place mostly on race weekends in front of everyone. The Honda, meanwhile, was already well-developed, with the four-cylinder Yamaha YZR-M1 nipping at its heels.

“Not to put it too bluntly, but the Honda guys are down there at the other end of the paddock polishing the windscreen, filling the thing up with gas and trying the next tire,” explained the 2000 world champion. “Everybody has problems, but Rossi’s concentrating on how he’s going to win the race; we’re revolutionizing the thing every practice. We’re just trying to get where they are.”

Lack of testing aside, Roberts is happy with the direction Suzuki chose. “I was relieved,” he said. “All of the training and preparation that I do, it was difficult to comprehend having to put that much effort into spending another year on a non-competitive two-stroke.

Even though we were developing a prototype, at least it was the future.”

After an upfront showing in the rainy, season-opening Japanese Grand Prix, where AllJapan Superbike Champion Akira Ryo finished second, crossing the line 1.5 seconds behind race-winner Rossi, it was a rollercoaster year. Adding another variable to the mix, the team began the season on Dunlops, pretty shocking considering all of the top runners were Michelin-shod.

“Mentally, I tried to make it an advantage,” said Roberts. “Nobody was really happy with it, though, especially the engineers. They were asking about the chassis, but all I could say was, T can’t tell you about the chassis because I don’t know what the tires are doing.

I’m spinning all over the place.’

“We knew it was going to be more difficult,” the 29-year-old Californian said about the tire situation, “but we got so overwhelmed. It was just another variable that we didn’t need.” So the decision was made to go back to Michelin. But the French tire-maker could only provide the team with the previous year’s rubber, and only in standard soft, medium and hard compounds. Still, results immediately improved. Roberts scored nine top-10 finishes in 16 races, including a fourth in Portugal and a third in Brazil. At the latter round, he led in the rain for more than half the event before being passed by Rossi, Max Biaggi and late-race-faller Carlos Checa.

“As much as I wanted to finish on the podium, I needed to build momentum for the rest of the year,” Roberts said. “I was coming back from surgery (to thwart arm pump, caused by trying to manage the four-stroke’s added heft combined with having to blip the throttle while downshifting under braking), and Suzuki needed to see someone finish. When Checa and Biaggi came by me at the same time, I was really disappointed because I felt we had done enough to get on the podium. I didn’t realize there were three guys piled up just waiting for me to move out of the way.”

And so it went. The Suzuki was consistently down on top speed, clutch and engine-braking problems spoiled comer entries, and a narrow, spiky powerband-relative to the Honda, at least-stalled comer exits.

“The bike did get better throughout the year,” admitted Roberts. “It was scary, though, because it was really hard to concentrate. The bikes are so loud now. I’d get into a comer and the Honda guys would be gassing their bikes so much sooner because the V-Five has so much less torque. Honda built a V-Five because it wanted better tire life, less engine braking and, in theory, less torque. When they’re in front of you-or behind you, for that matter-and they’re opening the throttle, you have to be really disciplined to not get into it, too. Because if you do, you’re going to fall down.

“In my opinion, there aren’t a lot of guys who could do what we were doing,” he continued. “Sete helped us quite a bit because he never gave up. Generally, one of us would have bad luck. It’s really hard to be consistent when you’re having engine failures, gearbox failures, stuff of that nature that would take Sete or me out of a couple of practices and kind of dictate where we would be on the race weekend.”

Gibemau left the team at the end of the season, taking the team’s biggest sponsor, Telefonica Movistar, with him. This coming season, the Spaniard will ride a Honda RC21IV for Gresini Racing. He has already tested the V-Five and was blown away by its performance. Said Roberts, “Sete told me, ‘I’m doing the same things I was doing on the Suzuki-sliding into comers, sliding out of comers-but when I cross the line, I’m looking at a lap time that is 1.5 seconds quicker!"

Replacement Hopkins has a full year of MotoGP under his belt, having spent last season on a Red Bull-backed Yamaha YZR500. While he’s glad-proud, even-to have raced one of the legendary twostrokes, he used prior experience on productionbased Suzuki GSX-Rs in AMA Formula Xtreme competition to get a grip on the GSV-R. By the end of the Sepang test, the 19-year-old Californian had lapped within .1-second of Roberts Jr.’s times. But he was also trying very hard, having cracked the upper fairing and dented the gas tank climbing all over the bike.

“I’m very impressed with what I’ve seen from John during the past three days,” said Team Suzuki Crew Chief Stuart Shenton. “He’s very professional. He turns up and he’s ready to go. His feedback has been good, too.”

“I couldn’t imagine being 19 and being in John’s position,” added Roberts. “But he’s handling it extremely well. He’s so enthusiastic about everything.”

Schwantz spent his entire GP career on twostrokes and hasn’t ridden a current Superbike, so he was even less sure than Hopkins of what to expect from the four-stroke GSV-R-or from himself, for that matter. After all, at 38 years of age, he’s no longer a bright-eyed adolescent on a meteoric rise to racing stardom.

“It’s really, really fast,” he related following his first outing on the bike. “It seems to handle well, but at my pace, it’s going to handle well. Whenever anyone rode my bikes, if they were a second or even half a second slower than me, I didn’t think much of anything they said.”

After a second session, Schwantz was more confident, even beginning to slide the bike a bit. “Compared to Kenny’s 500 two-stroke that I rode two years ago, the GSV-R is a little easier to ride because it has a big gas tank on it. I’ve got something that I can put my leg against to pull the bike into corners. On the 500, all I had was the top inch, maybe 2 inches of the tank.

“Once you go to neutral throttle, though, the GSV-R wants to stand up and not finish the corner,” he continued. “It doesn’t want to change direction on the gas, either. Part of it, I think, is that the bike is really heavy on the front; everything is based around the front of the motorcycle instead of being a nice, neutral-feeling piece. If you run it off into a comer, for example, it’s turning as good as it’s going to turn. If you miss the entrance to a comer, you’re not going to be able to get it back. You’re just going to have to get out of the throttle. If you don’t, it could be catastrophic.”

Slipper clutches are all the talk in MotoGP-and the bane of seemingly every four-stroke MotoGP pilot, including Rossi. The Suzuki currently uses a conventional ball-bearing/ramp design that also posed a few problems for Schwantz. “It feels like everything happens at the lever’s full extension,” he explained. “You go from completely released to completely engaged in 10 or 15 percent of the lever’s throw. It you had it somewhere between, say, 40 and 100 percent, where you could slip the thing a little bit, it would be a lot more user-friendly.”

“I want to use the clutch, but I can’t,” added Roberts. “I have no control. I’m totally a prisoner to it. When it’s done doing what it’s going to do, then I can tip the bike into the comer.”

In all, Schwantz got in more than 30 laps-equivalent to 1.5 race distances-and eventually got within 5 seconds of Roberts’ and Hopkins’ times. In fact, by his third and final session on the bike, he was circulating well within the 107 percent cut-off for qualifying at last October’s GP. This, while astride a strange motorcycle, on a track he’d never ridden before and shifting GP-style-one-up, five-down-opposite of the street pattern he grew up with and stuck to throughout his career.

“I’m having to really, really concentrate-hard, hard, hard-on shifting,” he said. “The gearbox works great-the electric shift, everything-but I’m having to think about it everywhere. If I were to backshift coming out of one of those comers, it wouldn’t be pretty. I already have a bad taste in my mouth from Malaysian hospitals. I’ve been there enough, and I don’t want to go back.”

Between sessions, the Suzuki crew crowded around the former champ as if he were still part of the squad. “He has a very strong synergy with the team,” explained Shenton, who was paired with Schwantz during his championship-winning season. “You could probably cut Kevin open and find ‘Suzuki’ written through him. His character and personality were always his strong traits. He’s a professional, but he brings a certain boyish enthusiasm to anything he gets into, and it rubs off on the people with whom he surrounds himself.”

When he was racing, Schwantz was pretty much the underdog. He didn’t always have the best-handling bike on the grid, and the Suzuki was never the fastest or most powerful. Against the odds, though, he managed to win races-a lot of races. In 1988, his first full-time season,

Schwantz finished eighth in the standings, but won two races, including the opening round in Suzuka, Japan.

“I’m willing to push it that extra bit,” he said at the time. “I really want to win bad.”

Schwantz didn’t attend any GPs in 2002. He didn’t catch many of the races on television, either. But he read the results and just like everyone else, formed an opinion about the Suzuki, its progress and the level of effort that Roberts was putting forth.

“So, what’s going on with Kenny,” I had asked him mid-year.

“Well, you know,” Schwantz began, “Kenny’s got his championship. And he’s married now...”

Ouch.

Now, however, after having actually ridden the GSV-R and gotten a better understanding of what Roberts and Suzuki are up against, Schwantz has changed his tune.

"I watched Kenny win the championship in 2000, and saw him dominate races from start to finish," he said. "I gen uinely think his ability level is right there with the rest of them, but motorcycle racing is a tricky sport. You’ve got to be 100 percent confident in your equipment and in yourself. Maybe his approach this year was, T don’t want to do anything silly. I don’t want to bang myself up. We’re trying to do something with a motorcycle that’s really in development.’”

And therein lies the root of the problem. With a rumored six Hondas on the grid next year, plus four Yamahas, two Ducatis, two Aprilias, a V-Five Proton, at least one Kawasaki and who knows what other hybrids, Suzuki has a lot of work to do. More importantly, for the bike to continue to improve, the riders-Roberts in particular-must stay healthy. Schwantz, for one, is keeping the faith.

“I think Suzuki is a lot more competitive now than they would have been had they stayed with the two-stroke,” he said. “Short-term, it’s going to be difficult. Fve got as much confidence in Suzuki as anybody out there. I’d like to think they’re going to win some races next year. Judging by the way this test went, it could be Roberts Jr., it could be Hopkins.”

So, was the GSV-R experience worth traipsing halfway around the globe?

“Even if I had only gotten to do five laps,” Schwantz told me on the flight home, “it would have been worth it. At the end of the day, the guys asked if I wanted another set of tires. That alone was pretty special.”

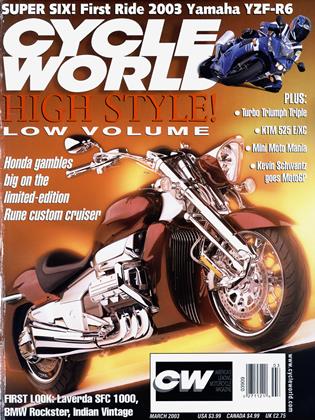

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Up Front

Up FrontResurrection, Inc.

March 2003 By David Edwards -

Leanings

LeaningsFamous Harley Myths

March 2003 By Peter Egan -

TDC

TDCBurning Race

March 2003 By Kevin Cameron -

Departments

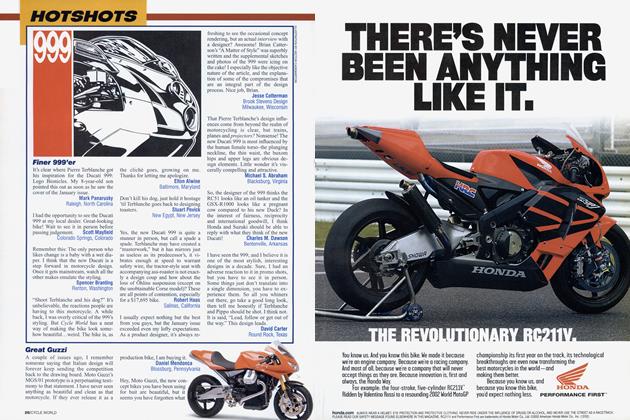

DepartmentsHotshots

March 2003 -

Roundup

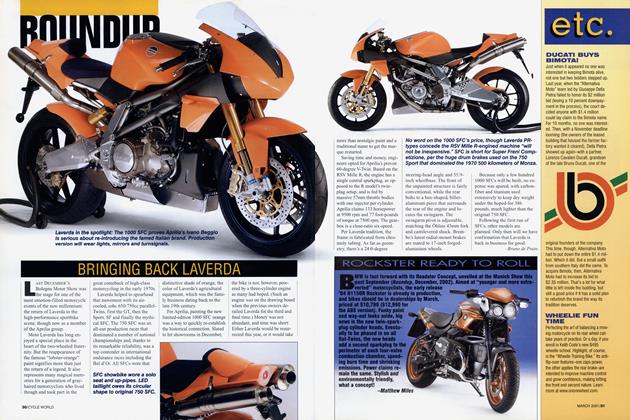

RoundupBringing Back Laverda

March 2003 By Bruno De Prato -

Roundup

RoundupRockster Ready To Roll

March 2003 By Matthew Miles