CYCLE WORLD GETS BUSTED, PART II

Nailed By A Subtle Form Of Speed Trap, Rick Kiser Is Glad He Fought Back

DAN HUNT

IF YOU'VE JOINED us only recently, "Part I" of this continuing drama appeared in the April '70 issue of CYCLE WORLD. It was the true tale of a successful "not guilty" plea entered by myself and Bryon Farnsworth in traffic court.

"Part II" began a few weeks ago when our mailboy, Rick Kiser, stumbled into the office and announced: "I just got a ticket for doing 40 in a 25.”

“Were you?” I asked.

“No, I was doing 35 because I saw the cop turn around and follow me, and I thought 35 mph was the speed limit there.”

“What are you going to do about it?” “Pay it, I guess. Who’s going to believe me?”

TURN-AROUND OFFICER

I believed him, particularly after he told me that the arresting officer had been going the other way and had turned around to follow him —after Rick had just passed over a severe dip in the road that is extremely uncomfortable to negotiate at more than 25 mph.

Nobody would be so stupid as to maintain 40 mph in a residential area with a squad car on his tail. Rick is no angel, but had a tenuous record of tickets. So he was cooling it. And his brother was with him and could testify that he was doing only 35 mph.

“Plead ‘not guilty’,” I said. “At worst you’ll get your fine reduced.”

And perhaps he could be acquitted entirely, for there were other aspects of the situation in his favor.

AN OBSCURED SIGN

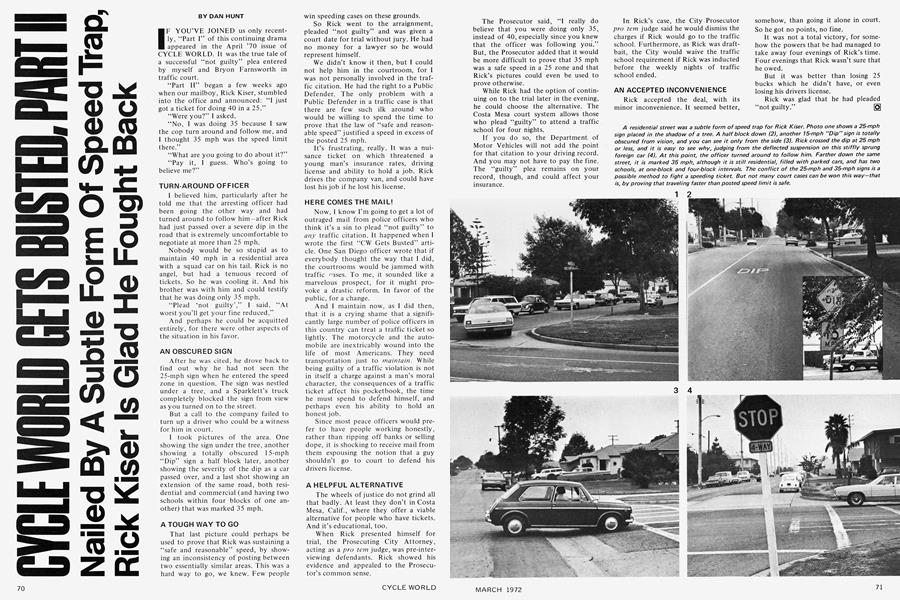

After he was cited, he drove back to find out why he had not seen the 25-mph sign when he entered the speed zone in question. The sign was nestled under a tree, and a Sparklett’s truck completely blocked the sign from view as you turned on to the street.

But a call to the company failed to turn up a driver who could be a witness for him in court.

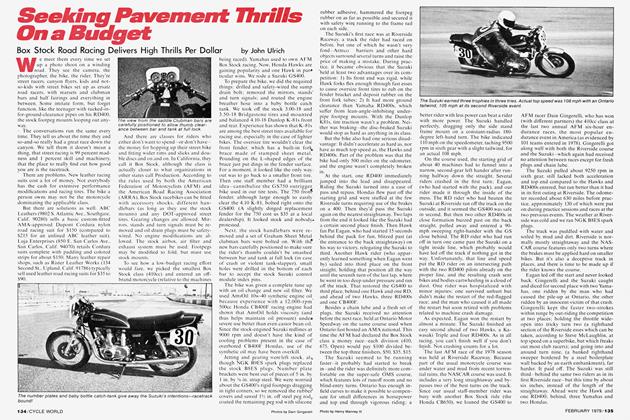

I took pictures of the area. One showing the sign under the tree, another showing a totally obscured 15-mph “Dip” sign a half block later, another showing the severity of the dip as a car passed over, and a last shot showing an extension of the same road, both residential and commercial (and having two schools within four blocks of one another) that was marked 35 mph.

A TOUGH WAY TO GO

That last picture could perhaps be used to prove that Rick was sustaining a "safe and reasonable" speed, by show ing an inconsistency of posting between two essentially similar areas. This was a hard way to go, we knew. Few people win speeding cases on these grounds.

So Rick went to the arraignment, pleaded “not guilty” and was given a court date for trial without jury. He had no money for a lawyer so he would represent himself.

We didn’t know it then, but I could not help him in the courtroom, for I was not personally involved in the traffic citation. He had the right to a Public Defender. The only problem with a Public Defender in a traffic case is that there are few such ilk around who would be willing to spend the time to prove that the law of “safe and reasonable speed” justified a speed in excess of the posted 25 mph.

It’s frustrating, really. It was a nuisance ticket on which threatened a young man’s insurance rates, driving license and ability to hold a job. Rick drives the company van, and could have lost his job if he lost his license.

HERE COMES THE MAIL!

Now, 1 know I’m going to get a lot of outraged mail from police officers who think it’s a sin to plead “not guilty” to any traffic citation. It happened when I wrote the first “CW Gets Busted” article. One San Diego officer wrote that if everybody thought the way that l did, the courtrooms would be jammed with traffic ^ases. To me, it sounded like a marvelous prospect, for it might provoke a drastic reform. In favor of the public, for a change.

And I maintain now, as I did then, that it is a crying shame that a significantly large number of police officers in this country can treat a traffic ticket so lightly. The motorcycle and the automobile are inextricably wound into the life of most Americans. They need transportation just to maintain. While being guilty of a traffic violation is not in itself a charge against a man’s moral character, the consequences of a traffic ticket affect his pocketbook, the time he must spend to defend himself, and perhaps even his ability to hold an honest job.

Since most peace officers would prefer to have people working honestly, rather than ripping off banks or selling dope, it is shocking to receive mail from them espousing the notion that a guy shouldn’t go to court to defend his drivers license.

A HELPFUL ALTERNATIVE

The wheels of justice do not grind all that badly. At least they don’t in Costa Mesa, Calif., where they offer a viable alternative for people who have tickets. And it’s educational, too.

When Rick presented himself for trial, the Prosecuting City Attorney, acting as a pro tern judge, was pre-interviewing defendants. Rick showed his evidence and appealed to the Prosecutor’s common sense.

The Prosecutor said, “I really do believe that you were doing only 35, instead of 40, especially since you knew that the officer was following you.” But, the Prosecutor added that it would be more difficult to prove that 35 mph was a safe speed in a 25 zone and that Rick’s pictures could even be used to prove otherwise.

While Rick had the option of continuing on to the trial later in the evening, he could choose the alternative. The Costa Mesa court system allows those who plead “guilty” to attend a traffic school for four nights.

If you do so, the Department of Motor Vehicles will not add the point for that citation to your driving record. And you may not have to pay the fine. The “guilty” plea remains on your record, though, and could affect your insurance.

In Rick's case, the City Prosecutor pro tern judge said he would dismiss the charges if Rick would go to the traffic~ schooL Furthermore, as Rick was draft bait, the City would waive the traffic school requirement if Rick was inducted before the weekly nights of traffic school ended.

AN ACCEPTED INCONVENIENCE

Rick accepted the deal, with its minor inconvenience.. It seemed better, somehow, than going it alone in court. So he got no points, no fine.

It was not a total victory, for somehow the powers that be had managed to take away four evenings of Rick’s time. Four evenings that Rick wasn’t sure that he owed.

But it was better than losing 25 bucks which he didn’t have, or even losing his drivers license.

Rick was glad that he had pleaded “not guilty.” GS

View Full Issue

View Full Issue