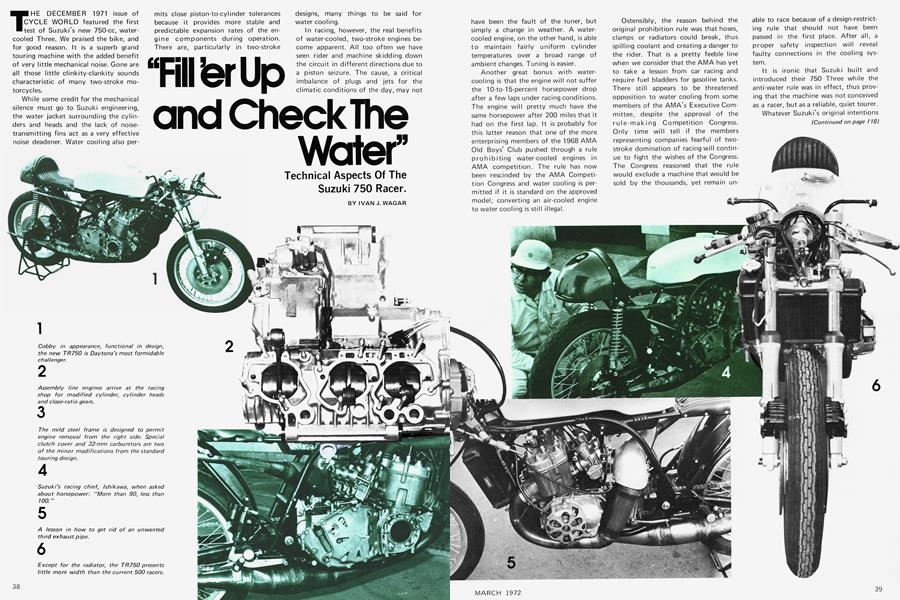

"Fill'er Up and Check The Water"

Technical Aspects Of The Suzuki 750 Racer.

IVAN J.WAGAR

THE DECEMBER 1971 issue of CYCLE WORLD featured the first test of Suzuki's new 750-cc, watercooled Three. We praised the bike, and for good reason. It is a superb grand touring machine with the added benefit of very little mechanical noise. Gone are all those little clinkity-clankity sounds characteristic of many two-stroke motorcycles.

While some credit for the mechanical silence must go to Suzuki engineering, the water jacket surrounding the cylin ders and heads and the lack of noise transmitting fins act as a very effective noise deadener. Water cooling also permits close piston-to-cylinder tolerances because it provides more stable and predictable expansion rates of the en gine components during operation. There are, particularly in two-stroke designs, many things to be said for water cooling.

In racing, however, the real benefits of water-cooled, two-stroke engines be come apparent. All too often we have seen rider and machine skidding down the circuit in different directions due to a piston seizure. The cause, a critical imbalance of plugs and jets for the climatic conditions of the day, may not have been the fault of the tuner, but simply a change in weather. A watercooled engine, on the other hand, is able to maintain fairly uniform cylinder temperatures over a broad range of ambient changes. Tuning is easier.

Another great bonus with watercooling is that the engine will not suffer the 10-to-15-percent horsepower drop after a few laps under racing conditions. The engine will pretty much have the same horsepower after 200 miles that it had on the first lap. It is probably for this latter reason that one of the more enterprising members of the 1968 AMA Old Boys' Club pushed through a rule prohibiting water-cooled engines in AMA competition. The rule has now been rescinded by the AMA Competition Congress and water cooling is permitted if it is standard on the approved model; converting an air-cooled engine to water cooling is still illegal.

Ostensibly, the reason behind the original prohibition rule was that hoses, clamps or radiators could break, thus spilling coolant and creating a danger to the rider. That is a pretty feeble line when we consider that the AMA has yet to take a lesson from car racing and require fuel bladders for gasoline tanks. There still appears to be threatened opposition to water cooling from some members of the AMA's Executive Com mittee, despite the approval of the rule-making Co mpetition Congress. Only time will tell if the members representing companies fearful of two stroke domination of racing will contin ue to fight the wishes of the Congress. The Congress reasoned that the rule would exclude a machine that would be sold by the thousands, yet remain un able to race because of a design-restricting rule that should not have been passed in the first place. After all, a proper safety inspection will reveal faulty connections in the cooling system.

It is ironic that Suzuki built and introduced their 750 Three while the anti-water rule was in effect, thus proving that the machine was not conceived as a racer, but as a reliable, quiet tourer.

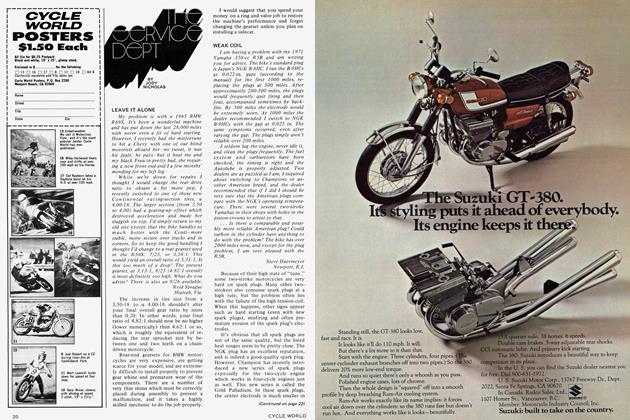

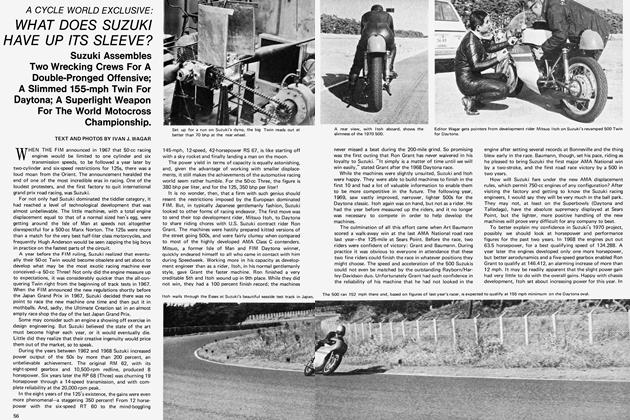

Whatever Suzuki's original intentions for the GT750, it is going to be a heart stopper in Daytona race form. It bears a resemblance to the all-conquering grand prix racers of the early 1960s, the agile and frighteningly fast mounts of Degner and Anderson which won world championships in almost every country in Europe. Even the massive 250-cc Four that was never really mastered has left its legacy to the TR750.

(Continued on page 118)

Continued from page 39

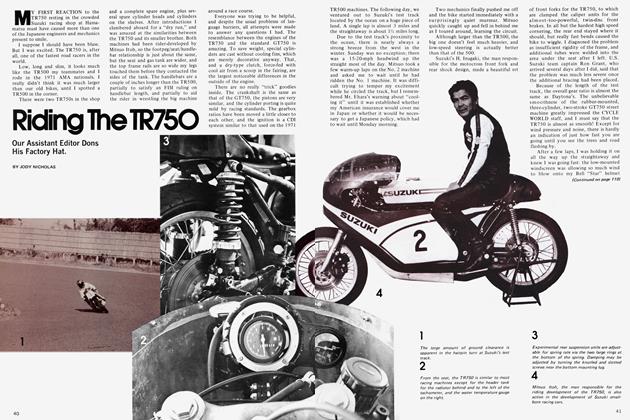

The Suzuki Daytona racer is, in every sense of the word, a hairy beast. Somewhat cobby, with an obvious lack of concern for appearance, the new machine is a monument to the stark, functional racing design. Like the Kawasaki 750 racer reviewed last month, engine changes to the Suzuki have been modest, despite its vicious appearance.

Internal gearbox ratios have been closed up to permit a narrower powerband for greater peak power. Port timing and pipe dimensions are almost identical to the current TR500 racing Twin, which is really not wild compared to the roadster. A new frame is being developed to handle the new horsepower figures and, as in the past, the material is mild steel, as opposed to the 4130 chrome moly so much in vogue lately.

The new racer features a beefed-up dry clutch housed in a cast magnesium, well vented cover. Brakes, front and rear, are discs. At this time, tests indicate that the fronts may be too powerful, so the 18-8 stainless steel donuts may be decreased from the present 200mm to something around 180mm in diameter, thus providing a worthwhile savings in unsprung weight.

Although the TR750 is quite massive in appearance, weight has been kept down to a respectable 380 lb. The width is not much greater than the current 500 racers, despite the need for radiator ducting in the fairing. In an effort to minimize the fairing size, and permit good ground clearance for cornering, the engineers have come up with weird piping for the third pipe. Assistant Editor Jody Nicholas has been taking some ribbing about his knee warmer on the left side of the machine, when really the cartilage problem is in his right knee. It would appear that something has been lost in the translation. Look out Daytona.