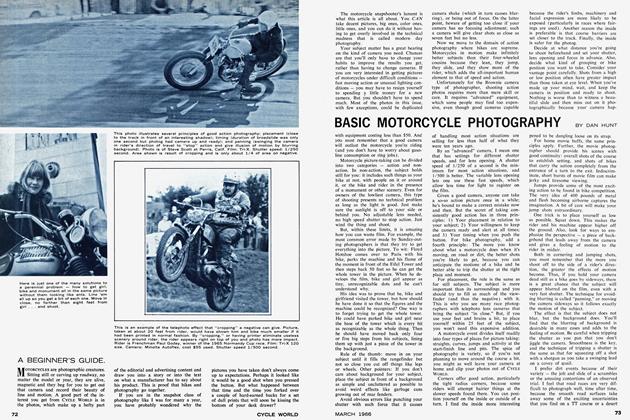

H-D for TT: THE LAWWILL LIGHTWEIGHT

DAN HUNT

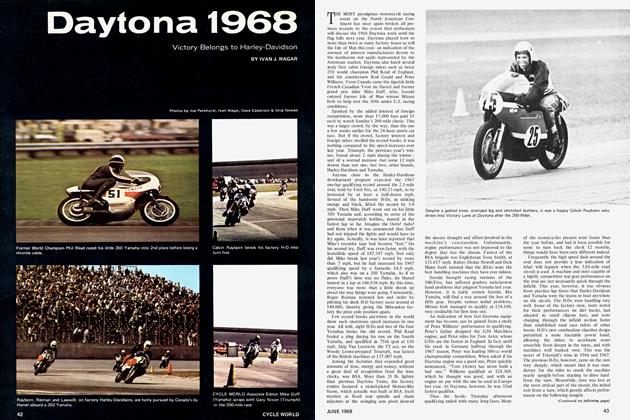

PROFESSIONAL TT racing, the all-American sport of turning a fast motorcycle left and right on an abbreviated ribbon of graded dirt, long has been the bailiwick of the 650-cc Triumph rider. Hence Mert Law-will, AMA National No. 18, has been largely ignored as a threat on the kidney bean circuits. This is because he rides Harley-Davidson. H-Ds have a built-in disadvantage when it comes to TT racing, for they are heavy, a trifle cammy, and tend to spin their wheels once the power band is reached.

But Mert has been making himself hard to ignore. Last year he won a TT national, a feat so unusual for H-D that the factory boys call it a “bonus” ride. This year Mert placed 2nd in the tough TT season opener at Ascot behind Skip Van Leeuwen, a Triumph rider who specializes in the Ascot TT. It was a proud 2nd for Mert, for he had to fight off a host of other home track specialists. As Mert says, “Those Ascot people are scientists, they aren’t there to fool around.”

But Mert is somewhat of a scientist too, which explains why his H-D is starting to romp loudly in Triumph country. It started in 1965 when he designed a new frame for his H-D flathead, which he used rather than the Sportster engine, because he believes the latter is too heavy and overly powerful.

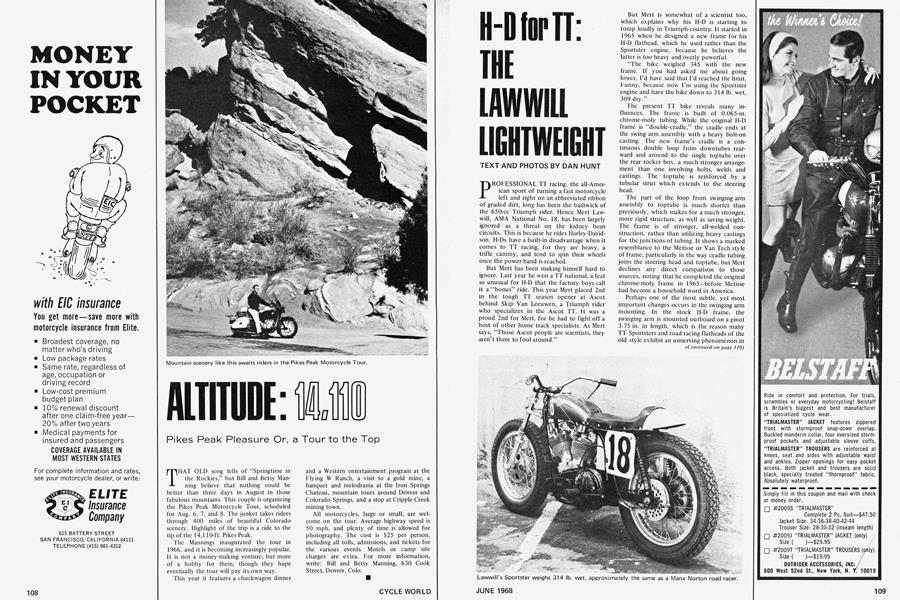

“The bike weighed 345 with the new frame. If you had asked me about going lower, I’d have said that I’d reached the limit. Funny, because now I’m using the Sportster engine and have the bike down to 314 lb. wet, 309 dry.”

The present TT bike reveals many influences. The frame is built of 0.065-in. chrome-moly tubing. While the original H-D frame is “double-cradle,” the cradle ends at the swing arm assembly with a heavy bolt-on casting. The new frame’s cradle is a continuous double loop from downtubes rearward and around to the single toptube over the rear rocker box, a much stronger arrangement than one involving bolts, welds and castings. The toptube is reinforced by a tubular strut which extends to the steering head.

The part of the loop from swinging arm assembly to toptube is much shorter than previously, which makes for a much stronger, more rigid structure, as well as saving weight. The frame is of stronger, all-welded construction, rather than utilizing heavy castings for the junctions of tubing. It shows a marked resemblance to the Metisse or Van Tech style of frame, particularly in the way cradle tubing joins the steering head and toptube, but Mert declines any direct comparison to those sources, noting that he completed the original chrome-moly frame in 1965-before Metisse had become a household word in America.

Perhaps one of the most subtle, yet most important changes occurs in the swinging arm mounting. In the stock H-D frame, the swinging arm is mounted outboard on a pivot 3.75 in. in length, which is the reason many TT Sportsters and road racing flatheads of the old style exhibit an unnerving phenomenon in bumpy turns and jumps. This is known as “Harley Hop” or “Milwaukee Wobble.” The pivot is too short, and leverage from forces acting on the rear wheel find little resistance at the pivot, which results in variable (and unpredictable) tracking.

(Continued on page 110)

The new pivot is much heftier in girth, and is 7 in. long. It is therefore less subject to side twisting forces. It is mounted inboard (“European style,” as Mert would say) on tabs welded into the interior curve of the cradle loops.

The swinging arm is similar to the squaresectioned Dick Mann swinging arms for BSA Victors (Mann no longer makes these, by the way, as he’s gone East with Yankee). Designed by Mert’s sidekick Jim Belland (who also did all the assembly work on the new frame), the new 4130 chrome-moly steel arm is stronger and several pounds lighter than standard.

There are three holes in each shock absorber mounting tab at the end of the arms; these allow the rear end to be set high or low depending on track condition. On a dry, dusty track, the setting would be low to keep weight rearward and increase traction. At Ascot night TTs, the damp clay lets the tires sink in and offers so much traction that the bike may be leaned over until it grounds, unless the high setting is used.

The suspension is comprised of a Ceriani road racing front telescopic fork and standard Girling shock absorber units at the rear. The road racing fork offers about 4.5 in. of travel; the longer motocross variety of Ceriani is unnecessary in professional TT racing by reason of the smooth condition of the tracks. These Cerianis, incidentally, are a standard H-D import.

While the front brake unit appears highly unusual, it is merely a standard Sportster brake with large holes in each side. Rear brake modification is far more drastic, and shows remarkable race season planning. Normally the rear chain sprocket is integral with the brake drum on the left side. Mert has turned the sprocket off the drum and moved it to the right side, while the brake remains on the left. The result is that he may now use the rear wheels from his flat tracker on his TT bike, greatly extending the choice of traction he has. He, like anyone else, has to stick to a budget and doesn’t wish to tie up his transporter space with superfluous wheel and tire combinations.

Lawwill’s treatment of the 883-cc Sportster XLR engine is highly unorthodox and shows a complete change in philosophy about race preparing a Harley for a twisting TT course. Not much has been done with special speed equipment. The only major changes are a Sifton cam (which actually is milder than a factory Sportster cam) and a set of tuliped racing valves which are available from the factory to anyone. Standard pistons provide 10:1 compression.

Mert says, “You can twist this engine on from idling all the way up to peak revs, and it won’t miss a beat.”

The secret to this performance lies with Southern California tuner C. R. Ax tell. Using a flow testing bench, Axtell completely reworked Mert’s cylinder heads. So it’s no surprise that the horsepower rating of Mert’s H-D is in the low 60s, hardly more than a stock sportster. But oh, my oh my, what a power band! It has put an end to excessive wheelspin-the bete noir of TT riders.

Almost as important was the lightening of the engine itself. The powerplant now weighs less than the 750-cc sidevalve he used to win the Castle Rock TT National last year. This takes some cleverness when the weight reducing process starts with greater capacity and the extra weight of the overhead valve engine.

Large areas and chunks of the crankcase have been trimmed for lightness. The outside diameter of the cylinder barrel fins was reduced. The fins are liberally drilled. The rocker boxes have had 0.060 in. removed from their surfaces. Aluminum bolts are used on the engine and other parts of the bike where little stress occurs. The left side footpeg is mounted directly to the side of the case cover, both to avoid grounding and to eliminate the extra weight of brackets curving up from the frame. On the right side, the peg is bracketed on the pivot mounting tab. A Kosman oil tank is used. The result is a low, lithe looking Sportster with less top hamper and an incredibly low curb weight, more than 100 lb. less than the showroom variety and about 30 lb. less than TT Harleys being fielded by several other national numbers. It may be thrown around with abandon, very much like a...well...like a Triumph.

The machine is the product of three years of refinement, so it will not be easily duplicated by Lawwill’s competition. Even as he talked with CYCLE WORLD he came up with an idea to eliminate another three poundssomething so simple that he’d overlooked it.

The friendly San Franciscan, who has the run of sponsor Dudley Perkin’s shop, has similar plans for his flat track racer. His target weight by the end of the season: 260 lb.! ■