To harness a HONDA

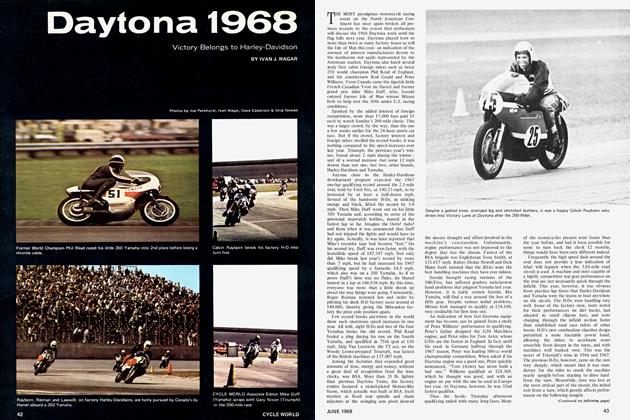

JAPANESE motorcycle manufacturers long have been famous for engines that deliver phenomenal horsepower. However, these same manufacturers are equally notorious for their seeming inability to design and construct racing motorcycle chassis with the capability to harness all that power.

Among the rumor and speculation that accompany the one, two, Honda, Suzuki withdrawal from grand prix motorcycle racing is a bit of hard news welcome to enthusiasts worldwide. Mike Hailwood this season is aboard a special machine unique among current grand prix motorcycles.

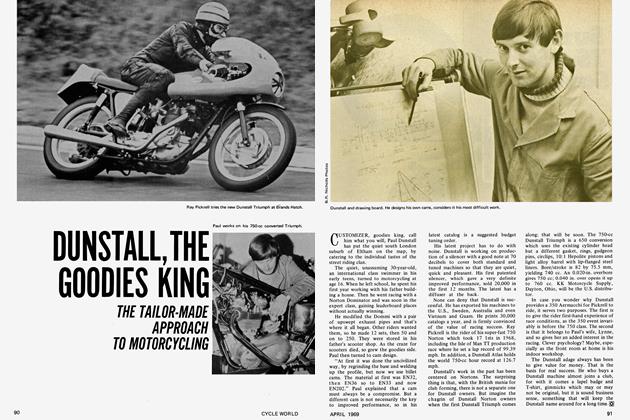

Perhaps Hailwood sensed, or had access to privileged information, that Honda’s growing disinterest in racing would result in eventual withdrawal. Whatever the reason, 14 months ago, Hailwood approached Ken Sprayson of Reynolds Tube Co., Ltd., of Birmingham, England, and invited the world renowned motorcycle frame constructor to assist in development of a grand prix special.

Unfortunately, time was lacking and Reynolds was unable to manufacture such a one-off frame. Hailwood was forced to make alternate arrangements for a special frame. This was built in Italy. Powered by a 500 Honda Four engine, this chassis was tested in numerous non-championship international race meetings, and in practice before the 1967 West German GP at Hockenheim. Hailwood’s development project never was officially recognized by Honda, but it now appears that the Japanese firm has agreed-or perhaps has not disagreed-with the Hailwood/Sprayson alliance when it was reaffirmed in September 1967.

Design and re-design of the frame required six months. Actual construction was completed in approximately two weeks.

Reporting on the project, Sprayson says that the size and shape of the Honda powerplant caused him to push aside all previous designs, and to plan a wholly new frame to accommodate the bulky Honda engine.

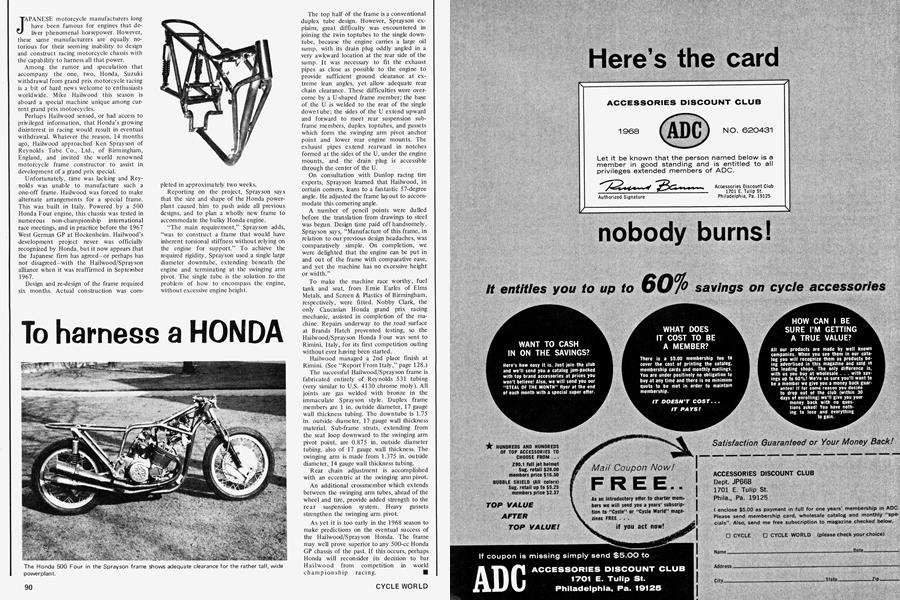

“The main requirement,” Sprayson adds, “was to construct a frame that would have inherent torsional stiffness without relying on the engine for support.” To achieve the required rigidity, Sprayson used a single large diameter downtube, extending beneath the engine and terminating at the swinging arm pivot. The single tube is the solution to the problem of how to encompass the engine, without excessive engine height.

The top half of the frame is a conventional duplex tube design. However, Sprayson explains, great difficulty was encountered in joining the twin toptubes to the single downtube, because the engine carries a large oil sump, with its drain plug oddly angled in a very awkward location at the rear side of the sump. It was necessary to fit the exhaust pipes as close as possible to the engine to provide sufficient ground clearance at extreme lean angles, yet allow adequate rear chain clearance. These difficulties were overcome by a U-shaped frame member; the base of the U is welded to the rear of the single downtube; the sides of the U extend upward and forward to meet rear suspension subframe members, duplex toptubes, and gussets which form the swinging arm pivot anchor point and lower rear engine mounts. The exhaust pipes extend rearward in notches formed at the sides of the U, under the engine mounts, and the drain plug is accessible through the center of the U.

On consultation with Dunlop racing tire experts, Sprayson learned that Hailwood, in certain comers, leans to a fantastic 57-degree angle. He adjusted the frame layout to accommodate this cornering angle.

A number of pencil points were dulled before the translation from drawings to steel was begun. Design time paid off handsomely. Sprayson says, “Manufacture of this frame, in relation to our previous design headaches, was comparatively simple. On completion, we were delighted that the engine can be put in and out of the frame with comparative ease, and yet the machine has no excessive height or width.”

To make the machine race worthy, fuel tank and seat, from Ernie Earles of Elms Metals, and Screen & Plastics of Birmingham, respectively, were fitted. Nobby Clark, the only Caucasian Honda grand prix racing mechanic, assisted in completion of the machine. Repairs underway to the road surface at Brands Hatch prevented testing, so the Hailwood/Sprayson Honda Four was sent to Rimini, Italy, for its first competition outing without ever having been started.

Hailwood managed a 2nd place finish at Rimini. (See “Report From Italy,” page 128.)

The successful Hailwood/Sprayson frame is fabricated entirely of Reynolds 531 tubing (very similar to U.S. 4130 chrome moly). All joints are gas welded with bronze in the immaculakte Sprayson style. Duplex frame members are 1 in. outside diameter, 17 gauge wall thickness tubing. The downtube is 1.75 in. outside diameter, 17 gauge wall thickness material. Sub-frame struts, extending from the seat loop downward to the swinging arm pivot point, are 0.875 in. outside diameter tubing, also of 17 gauge wall thickness. The swinging arm is made from 1.375 in. outside diameter, 14 gauge wall thickness tubing.

Rear chain adjustment is accomplished with an eccentric at the swinging arm pivot.

An additional crossmember which extends between the swinging arm tubes, ahead of the wheel and tire, provide added strength to the rear suspension system. Heavy gussets strengthen the swinging arm pivot.

As yet it is too early in the 1968 season to make predictions on the eventual success of the Hailwood/Sprayson Honda. The frame may well prove superior to any 500-cc Honda GP chassis of the past. If this occurs, perhaps Honda will reconsider its decision to bar Hailwood from competition in world championship racing.