STRANGE COMPANY LOOSE ON THE ROAD

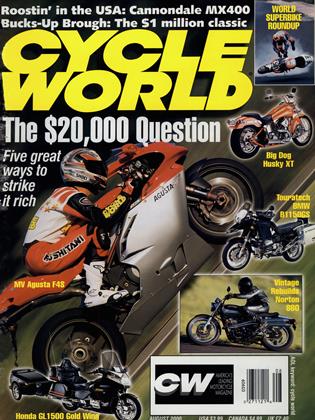

Italian exotica, American muscle, a rebuilt Britbike, a Winged road tool or a round-the-world Beemer? That's the $20,000 Question

PHIL SCHILLING

YOUR WONDERING EYES HAVE GOT IT right. These five motorcycles-Big Dog Husky XT, Norton SS880, MV Agusta F4S, BMW R1150GS and Honda Gold Wing SE-do make for strange company. Strange, but by no means incomprehensible.

The connection begins with the Almighty Dollar. In this group of five, the median price is $20,000 give or take. The Big Dog tops $22,000, the MV F4 slips in at $19,000, and our particular Norton special, built to customer order, pencils out at $20K. While a standard RI 150GS retails for $14,190 and a stock Gold Wing SE costs $18K, the BMW and Honda featured here have been accessorized up: Touratech gear raises the GS to $18,644, and the J&M and Bushtec accessories for the Gold Wing lift its price to a luxuriant $26,000.

In today’s Jackpot Economy, spending large for a motorcycle has become increasingly commonplace.

Indeed, according to one industry source, perhaps one-third of all big street motorcycles sold this year in the United States will roll off the showroom floor-tax, title and license-at 20 grand or more. Heck, the average price for a new streetbike last year was $11,000. That should hardly surprise us in an economy where the cost of a typical new car has reached the mid-20s, and a two-bedroom fixer-upper in California’s Silicon Valley can top a cool half-mil.

For the moment anyway, a boom-time mentality exists, consumer confidence is high, and spending for luxury goods continues widespread and strong. That’s wonderful for motorcycles that are luxury goods.

In good times, things like motorcycles sell in great numbers. So you buy a new bike, but soon enough you keep meeting motorcycles on the road exactly like yours. Instead of special, your motorcycle begins to feel ordinary. You want something more exclusive, apart from the crowd, more extreme.

These enthusiast desires for the next new thing create opportunities for manufacturers to build more radical and costly machines. Small companies can offer edgy bikes and options on which large makers wouldn’t or couldn’t gamble. In the end, market forces produce machines like this gang of five. All are highly individual and exclusive, whether they reached that status by being custom-built, or factory produced in limited quantities, or accessorized to the hilt. In a very real way, these five bikes showcase the motorcycle prosperity of the New Economy. Just do the math.

The chance to put this gilded showroom on the road for three days proved irresistible. The scheme for this prosperity excursion materialized at the highest levels, somewhere between the offices of Editor-in-Chief David Edwards and Managing Editor Matthew Miles. Shortly thereafter, my phone rang. Though young Mr. Miles understood that I wasn’t cutting-edge current on equipment, he did know my longtime attraction to exotic motorcycles and inquired whether I might be interested in joining the Cycle World expedition.

Slap that defibrillator on Rip Van Winkle. Zap! Of course. Yes. Yes!

Because I owned an MV Agusta 750 America about 25 years ago, the new F4 intrigued me. So did David

Edwards’ Norton, built by Kenny Dreer at Vintage Rebuilds up in Oregon. I remember the old days when kickstarting a high-compression Norton Twin was a grim contest between man and machine. In that ritual siege at the lever, I routinely succumbed to cold-steel British determination. What would be Edwards’ trick? Would he just will his Commando into combustion?

Joining Edwards and Miles as official members of the road party were CW’s Assistant Art Director Brad Zerbel and Mark Hoyer, Sports Editor. Zerbel owns both street and dirtbikes, and right now his favorite motorcycle is his KTM 620 R/XC Dual Sport.

Brad’s a serious case.

About Hoyer: Someone with the title “Sports Editor” is an individual to treat with caution. To me, Hoyer’s business card suggested he might go through back protectors like paper towels. Not to worry. It turns out that Mark has led a charmed life. He once owned an old Aston Martin for two years and it didn’t murder him. Currently, he runs a pumpkin-orange Laverda Triple.

Our route would run from the Sonoma Valley, north of San Francisco, south westward to Point Reyes Station, and then down the coast to Stinson Beach and Mill Valley, across the Golden Gate Bridge, south along the Pacific Ocean, through Half Moon Bay and Santa Cruz, to Monterey. On the second day, we would take a southeast heading along Carmel Valley Road and other narrow blacktops and eventually intersect with Highway 101 running south; we would leave four-lane 101 at Route 154, hit the backroads of the Santa Ynez Valley and finish the day in Santa Barbara. The final leg would follow the ocean shore south, first along 101, and then via Highway 1 from Oxnard, through Malibu, to metropolitan Los Angeles and at last the CW offices in Orange County.

Before reaching Point Reyes Station, the Big Dog established itself as the most brutal, elemental motorcycle of the group. Engine vibration. Jarring suspension. Stretched-out riding position. Wimpy braking. Why, you question yourself, would anyone spend $22K for this Big Dog, a private-label custom Harley, when $16K would buy a functionally superior gen-yoo-wine Harley-Davidson?

The answers are engine and image.

Built on a Harley Evolution foundation, the Big Dog’s 107-cubic-inch S&S V-Twin has a knockout punch not found in Milwaukee. Maximum torque measures 105 foot-pounds, and horsepower nearly touches 100. For straight-ahead performance, the S&S engine goes way, way beyond HarleyDavidson’s new Twin Cam 88 (60-65 bhp; 72 ft.-lbs. at the rear wheel).

The Big Dog makes a perfect bike for ramp-to-ramp freeway charges. Blast up an on-ramp and lay down a socially incorrect wall of thunder; continue through first, second and third gears spewing glory noise; and then retreat down the first available exit ramp. Repeat as needed.

With this thunderous power comes impressive vibration. Mounted solidly in its “hidden-shock” (Softail-style) frame, the monster engine sends vibration rippling/throbbing/coursing through the motorcycle. Though pegs and bars agitate at various speeds, the seat has a mean, constant vibration that sizzles the rider’s butt just below the base of the spine.

Nevertheless, the bike does have a top-gear sweet-spot extending from 45 to about 62 mph. This is the Big Dog speed-window for cruising. Alas, the velocity of CW s excursion generally rose well above that window.

But Brad Zerbel missed a turn-off in San Francisco, got separated from the group, set his own pace, and spent most of the first day riding the Big Dog. While a little frayed by vibration and butt-sore from the seat,

Brad thought the Big Dog a great bike for cruising.

Taken strictly as a visual object, the Big Dog Husky XT is slick, polished, smooth, glossy and finely detailed. Someone who knew nothing about motorcycles might imagine that this sleek object would run with the silence and smoothness of an electric clock. But when motorcyclists describe the demeanor of the Big Dog, they employ a different vocabulary: rough-hewn, woolychested, tough as a foundry mitt.

How can something smooth and glossy also be wooly-chested?

One explanation is “investment.” The Big Dog’s mechanical roughness-the vibration, high-effort controls, heavy ’round-town steering, rocky suspension and exhaust rumble-invests this sleek orangeand-chrome objet with a tough-boy presence.

Suppose the Big Dog worked with the velvety smoothness and precision of Japanese products. Those qualities wouldn’t infuse the Big Dog with that rough-and-tumble substance. Without question, the motorcycle’s character comes from its big-inch American motor. The Big Dog can’t succeed on slick looks alone; it must be extreme in the way it runs. Hardcore, no-rubber, no-balance-shaft guys expect vibration and' roughness-those are essential parts of an experience to which The Look belongs.

Bold and striking, the Big Dog Husky XT is ultra-sleek and very clean. The $500 XT option and the $250 color-matched frame contribute significantly to the streamlined shape. A museum curator could love it. At $22,250 all up, the Husky XT is one fast, noisy way to the fashion edge of the cruiser world.

I had been waiting for some heavenly omen to signal the appropriate time to invite myself aboard Mr. Edwards’ 880 Norton. The omen, dear Anglophiles, began to fall everywhere around me. Rain.

For the moment, I had lost my fear of failure at the kickstart lever. Despite the fact that the 880 has a 10.5:1 compression ratio, I had seen, with my very own eyes, Edwards start that engine in two swipes, with the bike on its wheels and David straddling the saddle. Honesty, though, requires me to report that I yielded to British truculence yet again, and the Editor-inChief graciously stepped in and deftly summoned his Norton to life.

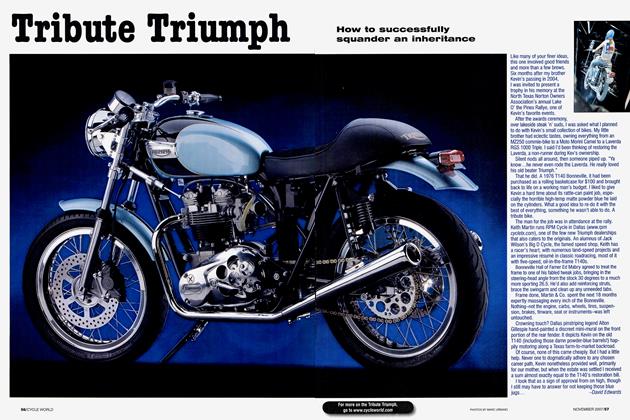

This particular motorcycle is a collaborative effort between Edwards and Dreer, the principal of Vintage Rebuilds. While Dreer is doing smallscale production (50 annually), this bike is a one-off. It reflects Edwards’ sensibilities and tastes and direction.

Money aside, most enthusiasts don’t have the time, patience and clear vision necessary to complete a oneoff-even with an expert like Dreer doing the work. Before commissioning a coachbuilt bike, you must know exactly what you want.

Edwards’ vision included an 880 with a large Interstate tank, modified Fastback seat and a high-pipe S-model exhaust-all Commando parts, but from various years. Though the sidepanels carry the banner “SS880 Sport Scrambler,” Norton never made such a model. Those unfamiliar with Nortons might well think Edwards’ bike is a stunning restoration rather than a revival motorcycle. New components, like the belt primary drive with accompanying ventilated cover and the Honda CBR600 fork internals, integrate harmoniously and seamlessly with traditional parts.

Norton motorcycles used to carry a small script “Made in England” on the frame; Dreer’s bikes bear the words “Re-Made in America.” It’s no joke. Dreer, for example, has recast the left-side crankcase half for durability’s sake. Then there are special 880cc cylinders, heavily reworked heads, JE pistons, rear cush hub, dual front disc brakes-the list goes on and on.

The New Economy prosperity allows Dreer to have a business that produces four dozen motorcycles annually. Most bikes will be Vintage Rebuild’s “standard” Sprint Special models, but within limits Dreer can also build an 880 to customer specifications.

CW has already called the VR880s the finest Nortons ever built. That statement is simply beyond argument. The proof is on the road.

After the Big Dog, the Norton seems so effortless. The engine settles into a top-gear baritone hum; your body relaxes into the sport-standard riding position; above 2500 rpm, engine vibration subsides and then almost vanishes courtesy of the Isolastic rubber-buffer system. The Norton feels agile, sure, predictable, smooth, serene. The pumped-up engine makes about one-third more power than the last Nortons of the mid-Seventies, good for low 12-second quarter-mile times.

There’s a wonderful familiarity about the SS880: riding position, switchgear, controls, weight, balance, feel. And versatility. Here’s an all-day motorcycle, comfortable and longlegged, at home on yawning interstates, tightly knotted one-laners and neon-lit boulevards. Yes, you have to (re)leam traditional shifting, on the right and one-up/three-down. And you’ll need to master the starting drill. But you get to ride for miles, almost anywhere, and make a personal statement about British tradition, American ingenuity and the enduring magic of classic motorcycling.

The year Norton bent into a death curl, Honda introduced the first-series Gold Wing. Today, 25 years of Gold Wing history divides pretty evenly; the first half belongs to the four-cylinder, the second to the Six.

As outfitted for this excursion, our

Gold Wing wound up on the wrong side of S25K. That tag makes the Honda entourage the most expensive hardware of this lot. Lotta stuff, though.

Americans associate certain elements with expensive or luxury goods. Size is one. In America, bigger is better. Weight is another. A heavy door knob beats a light one. Gadgetry is a third element. Americans judge things by the number and sophistication of onboard gadgets. Luxury goods do more tricks.

To many minds, the Gold Wing defines the expensive, luxurious motorcycle: large and spacious, impressively heavy (almost 900 pounds wet), and sophisticated and gadget-laden. It’s so American. The Gold Wing should be built in the USA, and it is.

From his earlier exploits, Mark reported that our Gold Wing had already been a willing accomplice on twisting backroads leading to Sonoma. The Wing, he allowed, was such a stable platform that it could be banked over until he heard grinding noises, whereupon he kept riding it through the comer on the sound itself. His passenger hadn’t had a problem with that technique, and neither did the $5500 Bushtec Quantum trailer packed with gear. Mark reported he could feel the trailer give the bike some steering input (through the hitch) in hard corners, but certainly nothing worrisome. The Gold Wing stayed its course.

I thanked Mr. Sports Editor for his enlightening report, noted his back protector was still intact, and vowed to ride the Gilded Wing Ensemble on the four-lane 101 Highway. There, the assembly found its real home. The Gold Wing moved majestically ahead at 85 mph, and the only sign of the trailer was its image in the rearview mirrors. Some noontime sidewinds drubbed the Gold Wing a bit; if the trailer amplified the buffeting, the effect was minor.

So vast is the Gold Wing that you feel as if you’ve taken the director’s seat in a large control room of a spaceship. Gold Wings do seem unearthly. The six-cylinder runs with incredible smoothness and eerie silence. The Gold Wing’s size, weight, smoothness and its incomparable flat-Six engine make this machine unique. You have other choices in touring bikes, but none are like a Gold Wing.

Without gadgets, the rider would be lost in the size and smoothness and silence of the Gold Wing. Going down a wide highway this bike almost takes care of itself. What’s a rider to do?

The Gold Wing needs gadgets. Space and silence have created a void into which gadgets must rush. Honda obliges with, among other things, a premium AM/FM/tape cassette, stereo surround-sound, headphone jacks for rider and passenger, and an exhaustive array of other bells and whistles and sirens.

Companies like J&M provide even more possibilities to keep rider and passenger engaged and entertained.

For starters, try special Arai helmets fitted with headsets. These connect to the Honda system and can bring in the stereo, intercom, and CB. J&M also sells an Alpine six-disc CD player; the head is right-hand handy while the changer mounts in the top trunk. The passenger can make choices by using a small hand-held remote. J&M can also modify your Valentine One radar unit to mate neatly with the Gold Wing, ditto for the Motorola StarTAC cell phone. With the J&M interfaces, everything plugs in.

After dealer installation, the interior of your helmet will buzz with activity. You could be listening to your favorite CD, hear the radar detector go off, have the phone ring for an incoming call, get your passenger on the intercom, switch to a tape cassette, then change your mind and listen to the radio. On the Gold Wing, you can be fully occupied and pay little attention to riding the motorcycle. Now that’s luxury in America!

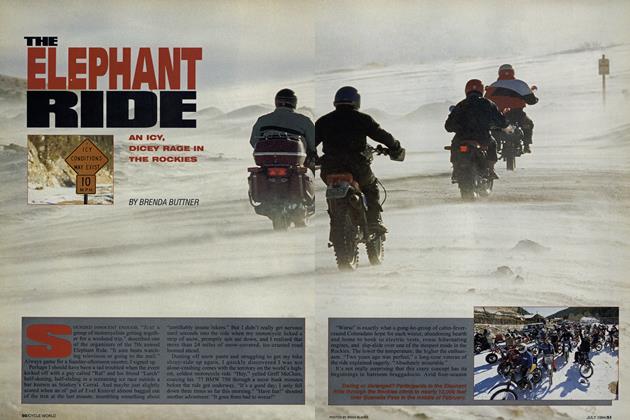

Twenty grand can buy a wildly different way to travel by motorcycle. Adventure-touring is athletic, active, gritty. The motorcycle becomes halfJeep, a vehicle to bear its rider into remote areas to camp, hike, back-pack, explore, sweat and test himself against God and Nature. Teddy Roosevelt would have embraced this kind of motorcycle adventure. Germans really love outdoor self-flagellation; it may stem from too much time spent Alpine yodeling in tight lederhosen.

With its RI 150GS, BMW provides a centerpiece for motorized outdoor life. OT testers discovered (October, 1999) that this boomer GS is a very capable sport-touring machine and legitimate streetbike with wide-band usability. And so long as the going doesn’t get too soft or rugged off-road, the stock 580-pound Twin makes a competent explorer. But understand this: The hiking part of your outdoor adventure should begin at the end of the fireroad.

Your dealer’s cash register will ring a new R1150 GS into your garage for $14,190. But the resourceful German firm Touratech {Touring Æallye Racing Technology) and its North American distributor Ride West Inc. can outfit an 1150 well beyond $20,000, though our feature bike checked in at $18,644.

Here are the highlights of that $4400 accessory tab. The monster Polyamid tank holds 41 liters or 10.8 gallons of fuel, up from the stock 5.5-gallon capacity. The giant fuel cell gives a range of about 400 miles. (By contrast, the Gold Wing’s low-fuel lamp lights within 150 miles.) A Touratech endurostyle saddle replaces the stock item.

The VP-45 Tank Combo includes 25liter center bag, map holder and two 10-liter sidebags. Touratech’s standard pannier system employs two cases, the left measuring 35 liters and the right 41 liters. Finally, two key items are head/cylinder guards and a heavy-duty steering stop that protects the expensive Telelever from damage in the event (surety?) of a tip-over.

So equipped, the RI 150GS looks like something out of a war movie.

Rather than pretty, the stuff is meant to be effective and serviceable. The lockable aluminum panniers are rectangular boxes for maximum space utilization; the lift-off tops aid easy, tight packing. When hit, aluminum may deform but it won’t shatter or fracture, so the panniers can be repaired in the field.

I felt drawn to the BMW. Perhaps the stark, almost military look of extreme function appealed to me. Maybe the heated handgrips won me over. It wasn’t the enduro-style Touratech seat; its flat shape and materials made riding uncomfortable after 150 miles. Still, the all-around versatility of the RI 150GS remained compelling.

I’ve crashed motorcycles at various speeds, and there’s no velocity I can honestly recommend. But rarely do I tip over at zero/nothin’//7<2¿/¿z. In the case of the GS, some basic figures signaled trouble. The height of the saddle exceeded the length of my inseam.

A 600-pound motorcycle, listing 2 degrees off vertical, simply overwhelmed my 160-pound frame. Flop! For an instant, I feared becoming the next big star in a crush video. Then it occurred to me. I had just had my first real adventure in adventure-touring.

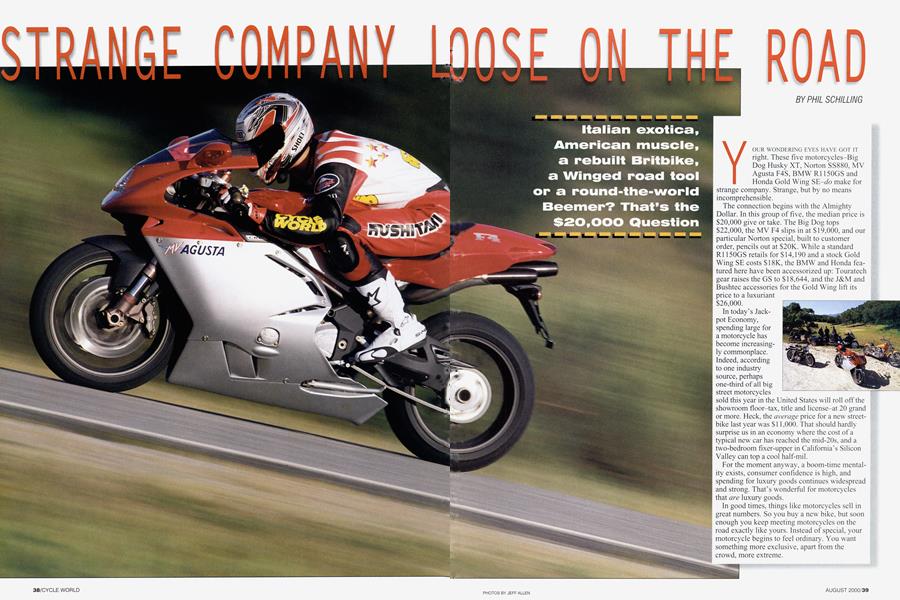

Everyone who tried the MV Agusta 750 F4 Strada found himself strungout in the land of enchantment. The thing’s a drug. The MV defines what a luxury good is in today’s Jackpot Economy: famous label, singular design, high technology, limited availability, exquisite craftsmanship, premium components, stunning details, dazzling beauty. Nineteen thousand dollars? Your eyes can see it. Your heart agrees. Buy on sight.

You could spend half the money and buy more performance. Do you care? A Suzuki GSX-R750 ($9399) spins out 124 horsepower on the dyno, up 15 on the MV’s 109 maximum. Both the Honda RC51 and CBR929RR list for $ 1 OK. Do you care? Should you? Performance without equal or rival isn ’t one of the hallmarks of luxury goods in this millennium. Try checking the reliability and accuracy of your classic Rolex against a drugstore Casio wristwatch.

On the road, the F4 Strada delivers a level of performance far beyond the ability of most riders to exploit. Those who could confidently probe that envelope came away impressed. The suspension was supple, soaking up sharpedged pavement breaks through the big sweepers on Carmel Valley Road. To Hoyer, the MV felt very planted, on its nose like a racebike, more supple than a Ducati 996 and perhaps easier steering. Coming through a series of comers, a good rider could probably dial into the power more easily on a 996-given the power characteristics of a 13,000-rpm inline-Four and its wonderfully frantic sounds, an MV rider wouldn’t roll into the throttle with impunity.

“It just feels business,” concluded the Sports Editor: no quirks like Ducati clutches; a complete, usable bike; a real tool.

Mr. Managing Editor Miles got off the MV prepared to write a check, almost. “If it just had a killer exhaust note, this bike would have everything,” he proclaimed. From the saddle, the rider hears the roaring/growling/ swirling intake noise, rising with the engine speed. It’s delicious. But the exhaust noise passes out the back, lost to the rider’s ears.

With ergonomics similar to the Ducati 996, the MV has the same aggressive riding position, requiring the same level of commitment to body torture. And those limits could be more severe than the Big Dog’s. Initially, the most impressive thing about the MV, Matt observed, is the way it looks. It takes your eyes prisoner, and then your soul. A GSX-R750, special though it may be, looks like something we’ve seen before. It resembles earlier models and follows the Japanese sportbike mold. As a familiar variation on a common theme, the GSX-R750 lacks the visual impact of the MV.

MV penman Massimo Tamburini has managed to create a distinctive new look, and being “new” with “eyeappeal” is the cornerstone of fashion. The F4 is many things, including a designer motorcycle. Its fairing might not be as aerodynamic as a GSXR750’s, but the MV bodywork captures your undivided attention.

The F4 is an objet d''art that works. Its place should be in the garage rather than the living room or gallery. The beauty of the shapes and the quality of the pieces would make a full afternoon of cleaning, detailing and polishing a pleasure. You could quarrel with the faux-carbon-fiber-imprinting used on the Strada’s plastic front fender and paneling, but again and again you’d be struck by the richness of the hardware. Hours after your afternoon polishing session ended, you’d find some excuse to return to the garage, check on something, and see it again.

The MV makes an apt symbol for boom-time extravagance. The F4 is extreme, exciting, expensive and exclusive. But there are other symbols, equally powerful and equally valid. At $20,000 or any other number, one man’s icon can be another man’s folly. A Big Dog owner might laugh at the enchantment that grips an MV owner.

A Gold Wing rider could ridicule the Big Dog and MV, both short-hop flashbikes. And so on.

Yet I think there’s a lesson from the road, learned in our strange company. We should greet differences with genuine curiosity and celebrate the stupendous variety in motorcycling. Because the most important thing about prosperity is choice. Forget that, and we’ll be the poorer for it.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Up Front

Up FrontNed's Sled

August 2000 By David Edwards -

Leanings

LeaningsCharacter Infusion

August 2000 By Peter Egan -

TDC

TDCTwo Crankshafts?

August 2000 By Kevin Cameron -

Departments

DepartmentsHotshots

August 2000 -

Roundup

RoundupEurope Gets Naked!

August 2000 By Matthew Miles -

Roundup

RoundupIndian's Sporting Scout

August 2000 By Wendy F. Black