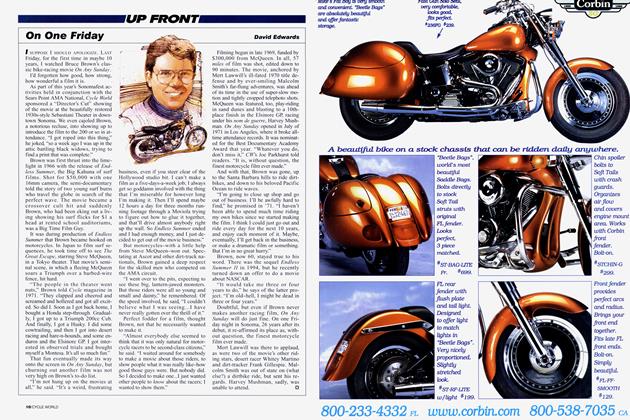

Sport for Two

BEST OFTHE "ORIGINAL" HARLEYS, THIS 1929 JD WITH SIDECAR WAS RESTORED FOR DAILY USE

ALLAN GIRDLER

DOING THE Right Thing can he as easy to do as it is to talk about. As in, it's a dark and stormy night, a lonely road, and the sack in the ditch contains. ..kittens. Obviously abandoned, obvi ously doomed unless the find er takes action, It doesn't require a degree in theology to instantly know that, nor to take that action. Same thing here. harlan and Sharon Bielefeldt follow the swapmeets. Two years ago they noticed some thing they'd never seen, a sporting old sidecar. Yeah, the then-owner said, it's a chair from the 1920s, a racing model, made for I larleyDavidson. Don't know what to do with it, he went on, SO its next attachment will he to a Honda Gold Wing.

If that~s not the moral equiv alent of doomed kittens, this isn't a motorcycle magazine. Better yet, six years beftre that, Sharon and I larlan had stumbled across the perfect match for the sidecar, an old JD I larley. Now, they don't have a permanent home: instead, they've got a parking place in Calif~rnia and a fifth-wheel trailer in which Harlan restores motorcycles, to be ridden. swapped or sold. Sharon is ncr VOLIS about two wheels, so the family car, so to speak, is a BMW with chair.

They wanted the JD and the owner was tired of trying to make big bucks and dropped the price, for cash on the barrelhead. But the low price still was higher than the Bie1ef~ldts had in their barrel at the time. But what goes around comes around-Sharon's cooking is famous on the show circuit and the checks they wrote to other vendors had never bounced-so the JD's then-owner said if the people who know you trust you, SO will I.

The ii) was parked with family, out of the cold and wet, because harlan and Sharon weren't sure what they wanted to do with it. Then came the sidecar and the next steps, the results of which arc shown here.

PHOTOS KIRK WILLIS

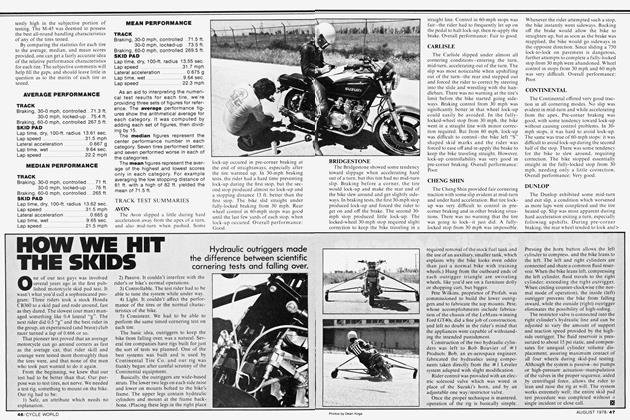

But first, some history. The JD is called the last of the origi nals because back at the beginfling of this century, when Bill Harley and the Davidsons were fooling with prototypes, the conventional engine had its intake valve above the exhaust valve, and the valve chamber, so to speak, was next to the piston. The valves were in a pocket, which is why the configuration became known as Intake Over Exhaust, or IOE, or as a Pocket Valve engine. The first production HarleyDavidson engines were IOE. There were countless changes-for instance, the very early Harleys used atmospher ic pressure to open the intake valve. And the first engines were Singles, joined in 1909 by a V-Twin. The engines got intake cams and gearboxes and chain drives, etc., but from 1903 until 1929 (excepting the eight-valve racers, of course) V-Twin Harleys were IOE.

There's a further complication in that there were lots of variations on the basic design. The standard Twin was the J, with one camshaft carrying four lobes, and with a displacement of 61 cubic inches. There was the Big Twin, displacing 74 inches and designated JD. Late in the production run, there was an upgrade, still IOE except there were two two-lobe camshafts, one for each cylinder. The two-cams came as the JH, the 61, and the JDH, the 74. The two-cam machines had smaller wheels and larger valves, by the way, while the canny shopper could get the two-cam's extras but with the single cam engine, labeled the JL. (Pause here to note that H-D's nimbleness with letters and proclivity for making lots of models from the same parts began way before the FLHTC or FXRD were dreamed of.)

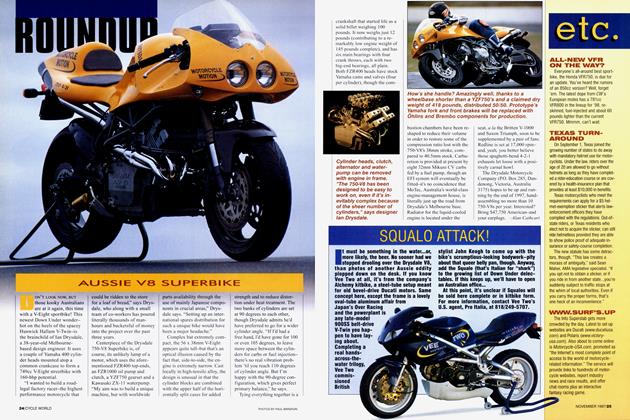

Anyway, the bike here is a JD, the one-cam 74, made in 1929. That was a distinctive year, not only because it was the final model year for the IOE engine. The `29s had dual headlights, done just the once, and used a fourpipe muffler that was made for the 1929 models only, but appeared on some of the 1930 production run, per haps because the unhappy economic events late in 1929 brought motorcycle sales to a virtual halt.

The mechanical details of the 1929 JD were conventional, with Harley's leading-link front suspension, rigidly mounted rear wheel, throttle on the right grip, hand shift for the three speeds forward, foot clutch on the left.

By the time of this 1929 JD, the motorcycle had been pretty much invented. The JD came with generator, lights, full brakes as mentioned and a sprung seat that made up (well, most ly) for the rigid rear end. The motorcy cle by then was viable transportation, which is why a JD can be ridden regu larly some 70 years later.

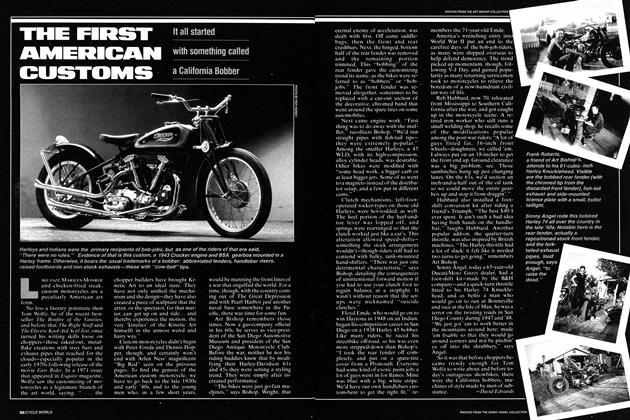

Sidecars are their own story. This example is an exhibit in a smaller-

make that obscure-bit of competition history. Right after WWI, there was a fad for sidecar racing on the flat dirttracks of the day. Harley-Davidson had offered sidecars from the beginning, and took part in racing as well. So it followed that the Goulding company, a Michigan outfit that was building side cars for H-D anyway, provided a nar rower body, streamlined by guess, for competition and sport.

This was a limited market. Most civilian sidecarists wanted the larger body, for wife and often kids, while at the other end of the spectrum a compa ny named Fixi, spelled just that way, no "e" please, came up with a racing rig that was, well, flexible.

Or maybe that's not quite the word. The Fixi frame was a linkage. At the entrance to a turn, the rider pushed and the passenger pulled and the rig leaned into the turn. At the straights, they hauled the thing upright again. This worked-so well, in fact, that on one occasion an Indian with Fixi sidecar finished a 10-mile national race with a time only one second slower than the winning time for the solo class.

Racing Fixis worked on Harleys as well, which meant that the Goulding sidecar, conventional in every way except for the narrow body and tapered tail and lack of any comfort features at all, wasn't a big seller. Only a handful were produced and several years of looking have turned up only one clear photo of the JD/Goulding sport sidecar.

Challenge is the best word here. Harlan and Sharon Bielefeldt had the JD and the sidecar, and they determined to build a rig that could have been on the road in 1929, never mind that this particular JD and this particular chair didn't leave the factory together.

Both components have obscure his tories. The bike was raced at some point. As acquired, it had been stripped offenders, lights and mufflers. Frame and lower end were 1929, but the cylinders were 1923 and 1924, racing parts. The JD was popular when new and is popular as a collector's item, so tracking down the major components wasn't too difficult.

Culture played a part, too. That fourpipe muffler was designed and offered because H-D thought customers want ed quiet machines. They didn't. Hundreds, perhaps even thousands, of buyers went for single or twin pipes, and the four-pipe assemblies were pushed into the back of the garage, meaning they now can be found at swap meets, which is why the assem bly on this JD looks so unused and so authentic. It's both.

For an example of restorer skill, look closely at the decal on the toolbox hung onto the JD's fork. Also new and original. Seems Harlan and Sharon have a habit, while on the road, of visiting each HarleyDavidson dealership they're near. The one picture of the Goulding sidecar and the JD, for example, turned up in Yucca Valley, California. And when the Bielefeldts dropped in on Skip Fordyce's store in Riverside, California, and asked if perhaps there were some really old items that had been left on the shelf or in the box, the Fordyce folks rooted around and there this decal was, the sort of luck that comes only from working at it.

Authenticity isn't everything. Some items couldn't be found. Harlan made that step for the sidecar's passenger from scratch; there are surviving examples of the larger Goulding sidecars, so knowing what to make wasn't tough. The seat was made from scratch also, with that old photo being used for the dimensions. Perhaps the most obvious and least authentic part on the rig is that nifty brake light, the one that says STOP. It was originally made for a Kissel, a sporting car built in Wisconsin during the 1920s. Licensing requires a brake light, and the era's right; Harlan figured an enthusiast in 1929 could have done it, so he did it now.

The paint is another of those obscure chapters. When the vintage motorcycle movement was new, emphasis was on stock, as seen in mass production. And stock in the 1 920s usually meant olive green for Harleys, red for Indians. Then research showed that in 1926, maybe even before that, H-D had a range of optional colors, some of which were really spectacular. By 1928, the range had expanded from a small number of colors and combinations to just about any shade on the market. The optional paint was a bargain even allowing for inflation. Some years, the full-color treatment went for an extra $30 or so, and in 1929, according to the latest research, the buyer could get two tones plus hand striping, all for $7.

The catch was, none of this was in the sales literature. The buyers or prospec tive buyers weren't told about the optional paints, they had to ask. Seems like a heck of a way to run a sales cam paign, but that's how they did it.

What matters here and now is that restorers have some new and eye catching choices that convention previ ously prevented. Kind of like when the surfers went motocrossing and by example persuaded the roadrace and flat-track crowds that wearing lime green or fire-engine red was no reflec tion on the rider's testosterone level.

In this example, the secret factory charts do show the color combination used for the JD and chair, but the own ers thought the factory's blue was too dark, so painter Roger Bowman, of Temecula, California, applied a lighter shade on grounds that the buyer could have made such a choice in 1929.

Some other choices were dictated by modern use, as in the diode to regulate voltage and the hidden plug for a trickle charger.

B ecause JDs had a long and recorded service record when in production, were in service for years after that and are popular for restoration now, the actual rebuild wasn't tough. Harlan has a workshop at his California parking place and the dinette has been removed from the family trailer to make way for a traveling toolroom, so the rebuild was less bother than you'd expect under constantly moving circum stances.

Daily use isn't the same as a daily commute. Instead, when the owners enter the rig in a show, they stipulate that they must be allowed to take their exhibit off display any time they please, so they can ride around the show, or the swap meet, or into town. How does it work?

Good enough to belie the rig's age. There's one semi-quirk. Notice that the sidecar wheel is nearly exactly oppo site the cycle's rear wheel. That's a marked contrast to modern practice, which puts the outboard wheel closer to the middle of the outfit's wheelbase. Racing rules limited how far back the side wheel could be put. Why? Because it's the equivalent of a solo machine's steering head rake, where the steeper the angle, the quick er the steering and the less stable in a straight line. The farther back the out board wheel, the easier and quicker the rig steers, and the more likely it is to tip over. Harlan says it's no problem for him-in fact, he kind of enjoys the agility. He knows what he's doing, of course, which should be the motto for all sidecar operators, anyway.

In any event, the trusty old engine starts easily and the rig will keep up with small town and show traffic, ditto the brakes. This is about as user-friendly as a restoration of this type machine is likely to be.

Ever notice that a rescued cat is often more affectionate than one born to privilege? Same thing here.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue