the hawk above, the crud below

phil schilling

BIKE THE GARAGE COMPANY

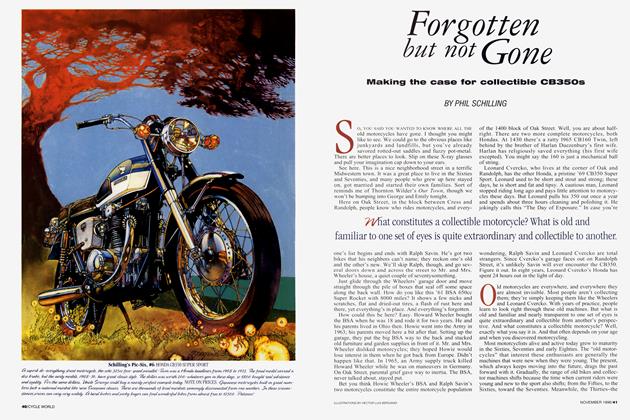

tHOSE ARE THE SIMPLE FACTS. FOLKLORE CONNECTS those facts this way: Honda tossed motorcycling into the suds with slick advertising; the sport emerged fluff-dried into middle-class respectability; and that allowed the company to sell Hondas by the millions. Of course, the full schematic is much more complicated and layered, but happily those complexities offer many paths toward understanding Honda's role in reshaping American motorcycling. One route is

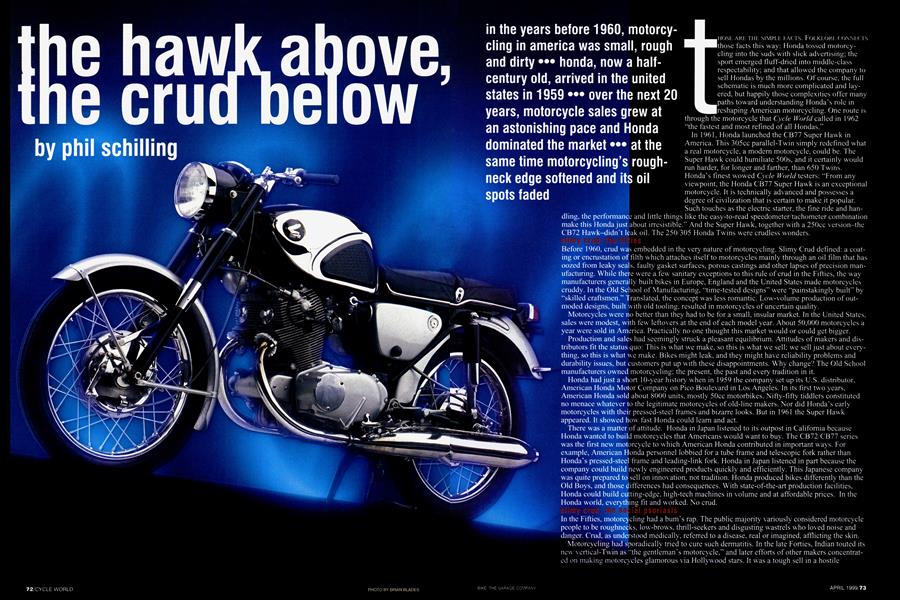

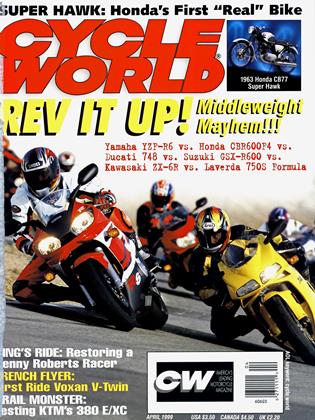

through the motorcycle that Cycle World called in 1962 "the fastest and most refined of all Hondas." In 1961, Honda launched the CB77 Super llawk in America. This 305cc parallel-Twin simply redefined what a real motorcycle, a modern motorcycle, could be. The Super Hawk could humiliate 500s, and it certainly would run harder, for longer and farther, than 650 Twins. Honda's finest wowed Cycle World testers: "From any viewpoint, the Honda CB77 Super Hawk is an exceptional motorcycle. It is technically advanced and possesses a degree of civilization that is certain to make it popular. Such touches as the electric starter, the fine ride and han dling, the performance and little things like the easy-to-read speedorneter'tachometer combination make this Honda just about irresistible." And the Super Hawk. together v~ ith a 250cc version-the CB72 Hawk-didn't leak oil. The 250305 Honda Twins were crudless wonders.

slimy crud, the fifties

Before 1960. crud was embedded in the very nature of motorcycling. Slimy Crud defined: a coat ing or encrustation ot't~lth which attaches itself to motorcycles mainly through an oil film that ha~ oozed from leaky seals. f~ulty gasket surfaces, porous castings and other lapses of precision man utiicturing. While there were a few sanitary exceptions to this rule of crud in the Fifties, the way manufacturers generally built bikes in Europe. England and the United States made motorcycles cruddy. In the 01(1 School of Manufacturing. "time-tested designs" were "painstakingly built" by `~skilled craftsmen." Translated, the concept was less romantic. Low-volume production of out moded designs. built with old tooling, resulted in motorcycles of uncertain quality. Motorcycles were no better than they had to be fbr a small, insular market. In the United States. sales were modest, with few lef~overs at the end of each model year. About 50,00() motorcycles a year were sold in America. Practically no one thought this market would or could get bigger. •~rodt,c~o9 and sales had seemingly struck a pleasant equilibrium. Attitudes of makers and dis

tributors fit the status quo: I his is what we make, so this is what we sell: we sell just about every thing. SO this is what we make. Bikes might leak, and they might have reliability problems and durability issues, bitt customers put up with these disappointments. Why change? The Old School manufacturers owned motorc~ cling: the present. the past and every tradition in it. lionda had just a short 1 0-year history when in I 959 the company set up its L~.S. distributor. American honda Motor Company on Pico Boule~ard in Los Angeles. In its first two years. American Honda sold about 8000 units. mostly 50cc motorbikes. Nifty-fifty tiddlers constituted no menace whatever to the legitimate motorcycles of old-line makers. 4or did I honda's early motorcycles with their pressed-steel frames and bizarre looks. But in 1 96 1 the Super Hawk appeared. It showed how fast I londa could learn and act.

There was a matter of attitude. Honda in Japan listened to its outpost in California because Honda wanted to build motorcycles that Americans would want to buy. The CB72 CB77 series was the first new motorcycle to which American Honda contributed in important ways. For example, American Honda personnel lobbied for a tube frame and telescopic fork rather than I londa's pressed-steel frame and leading-link fork. Honda in Japan listened in part because the companY could build newly engineered prodLicts quickly and efficiently. This Japanese company was quite prepared to sell on innovation, not tradition. Honda produced bikes differently than the Old i3oys, and those diff~rences had consequences. With state-of-the-art production facilities. Ilonda could build cutting-edge. high-tech machines in volume and at affordable prices. In the Honda world, everything fit and worked. No crud.

slimy crud,the social psoriasis

lii the Fillies, motorcycling had a burn's rap. The public majority variously considered motorcycle people to he roughnecks. low-brows, thrill-seekers and disgusting wastrels who loved noise and danger. Crud, as understood medically, referred to a disease, real or imagined, afflicting the skin. \lotorcvcling had sporadically tried to cure such dermatitis. In the late Forties. Indian touted its flC\\ veriicaJ-Twin as "the gentleman's motorcycle." and later efforts of other makers concentrat ed on making motorcycles glamorous via Hollywood stars. It was a tough sell in a hostile environment. Motorcycling kept its spots.

riding a super hawk was an act of rebellion.honda belonged to what was new, edgy, experimental and different about the '60s.riding a motorcycle was a finger-tip in the face of a uthority, a revolt against tightly wrapped straightness.

In the Fifties, Polite America rested on middle and upper classes that feared road rash and weeping scabs. Polite America celebrated authority, conformity, respectability and cleanliness. There was little tolerance for the blues, rockand-roll, beatniks, drugs, people of different colors, free love and dirt. Motorcycling fell outside the polite realm, but it had increasing company in the wilderness of non-conforming groups.

The tightly knotted self-confidence of “what was right and proper” loosened in the Sixties without totally unraveling. Throughout the decade the ties of social and political conformity held firm for many individuals. In most places, however, the cultural revolution of the Sixties recast what most people thought was right and proper. Events throughout the decade-Vietnam was the centerpiece-broke the majority’s confidence and faith in the authority of established institutions. Irreverence for authority became pandemic, and tolerance for differences increased. Experimentation was in, and so was “the new.”

In effect a break-line divided the Fifties and Sixties, and Honda found itself sitting on that edge. The maker of funtime motorbikes, Honda could appeal to conforming, respectable sensibilities with its enduring line, “You meet the nicest people on a Honda.” But Honda, the world’s largest motorcycle manufacturer, also belonged to what was new, edgy, experimental and different about the Sixties. Riding a motorcycle could be a finger-flip in the face of authority, a revolt against tightly wrapped straightness by young people who cared little about squeaky-clean social conventions. Thus, Honda motorcycles could be wonderfully ambivalent symbols, incorporating the dissonant values of the Fifties and Sixties. Riding a Super Hawk might be an act of rebellion, but a safe and respectable one.

slimy crud, the nineties

A Super Hawk seemed the perfect ride for the Slimey Crud Motorcycle Gang’s Cafe Racer Run outside Madison, Wisconsin (the Gang added an e to slimy to accentuate slime). Bruce Finlayson, a founder of the SCMG and my friend and co-conspirator since our college days, had a 1965 Super Hawk in his garage. Finlayson bought his first bike, a Honda, in 1962. For the next 25 years he owned only

Hondas, but today the Super Hawk is his sole Honda. October in Wisconsin can deliver crisp, golden days, decorated by blazing panoplies of colors held high in the trees. Almost 40 years ago, such fine motorcycling days drew me to the University of Wisconsin, Madison, where my head was-for a while-in graduate school before it joined the rest of me, and Finlayson, out on the road. The Slimey Cruds of the Nineties are a casual band of middle-aged motorcycle pals, maybe a dozen or so (including CWs own Peter Egan), who arrange these runs twice a year, the first one in May and the second in October. The autumn ’98 event marked the 10th such run, and “facilitate” better describes the SCMG’s role than “organize.” The event now proceeds almost entirely on word of mouth and memory. Though they worry about hero riders and hospital runs, the Cruds welcome all comers and machinery. Bring yourself whoever you are, ride whatever you wish, wear what you want, and come and go as you will. The run is

almost a spontaneous happening, a Sixties thing.

Cheerfully irreverent, the Slimey Crud Motorcycle Gang celebrates the cruddy tradition of motorcycling.

Hardly biker ruffians of the Fifties, the Cruds themselves seem like leftovers from the Madison’s Sixties counterculture. Most Cruds are longtime university townspeople who are comfortable, secure and self-assured. They do their own thing and don’t worry about respectability. Some Cruds might just spit in your eye if you called them “the nicest people.”

The day unfolds.

Assemble at Jake’s Bar &

Grill, in Pine Bluff, just outside Madison, beginning about 9 in the morning.

Congregate with 500-600 other motorcyclists. Check out the eclectic array of machinery that overflows from Jake’s parking lot and spreads out in four directions along Pine Bluffs main crossroads.

Older motorcycles, especially those cranky veterans from the oozc-and-cncrustation era, draw the most attention.

In the crowd at Jake’s there are very few old Hondas from the Sixties or Seventies because most everyone considers such bikes unremarkable motorcycles.

“There’s a reason for that view,” observes Finlayson. “It’s the banality of perfection.”

Pick up a map to the Sprecher Tap in Leland, Wisconsin, 60 to 80 miles away depending on your route and whim. Every possible combination threading from Jake’s to Sprecher’s is on the map, each has its moments of luscious, gorgeous, rolling countrysides. Figure on leaving Jake’s a little before noon,

between jake’s and sprecher’s

The Super Hawk comes to life reluctantly on full choke and promptly dies. The electric starter, a necessity for a highcompression (10:1) engine with generous Sixties-style carburetion (two “huge” 26mm units), spools up the 305 again. The Twin, still cold to the touch, settles down to a fast idle. Motorcycle riders half the age of the Super Hawk would, with little or no prompting, find the bike instantly familiar. Turnkey ignition switch. Electric starter button. Neutral light. Standard shift pattern. Clutch and brake levers in orthodox format.

bob oakes was to honda as st. paul was to christianity. he had a dazzling revelation that turned him into an apostle for honda.

Consider this: The Super Hawk, almost 40, lies nearly halfway back to the beginning of useful motorcycles. Yet the CB77 seems contemporary and common-and utterly lacking that quaintness of age its years might suggest. Should that surprise us? No. Modern motorcycles arrived with the Super Hawk. Leaving Jake's reveals why the Super Hawk was a revelation in the early Sixties. The CB77 packaged 500-class performance into 305 cubic centimeters. That meant getting to 60 mph in a tick over 7 seconds and breaking 100 mph on top. To get this performance from 19 cubic inches in 1961, Honda had to com press most of the Super Hawk's power into a band 3000 rpm wide and butt it up against a 9200-rpm redline. Riders called the CB77 cammy and rev-crazy. They were right. Below 6000 rpm, the Super Hawk pulls along with the smooth countenance and quiet civility of a Fifties Plymouth. At about 35 mph, the Honda murmurs forward at 4000 rpm in third gear. Snapping the throttles open at this point merely signals the engine to begin gathering speed deliberately. At six grand, the engine crosses out of its Twilight Zone. Cam timing gets in sync with the intake and exhaust tract plumbing. At 7000 rpm, the engine is fierce and willing. From the intake horns and mufflers comes a hard, hollow, pounding beat that, moments later, rises into a warbling wail. At nine k, the engine hits its peak power; at nine-two, the tach needle touches the redline, the stock

valve springs surrender and the valves float and clatter. No harm, no sweat. In 1961 other hot street engines might turn 7000 or 7500 rpm, but not with the regularity and impunity of the 9000-rpm Super Hawk. At even modest engine speeds (by Honda standards), most other motorcycles vibrated wickedly, a sure deterrent to using upper-end power. By contrast, the free-revving Super Hawk, with its crankpins set 180 degrees apart, was impressively smooth. But it took time for riders who had lived in a 5000-rpm world to adjust to Honda’s dizzy engine speeds and to trust in Honda reliability. After a while the dizzy did become the ordinary. That’s why, years later, spinning the 305 between 6000 to 9000 rpm all the way to the Sprecher Tap felt completely normal. With comer speeds above 40 mph, the CB77 always has a gear to fit the road and the rev range. Understand that a gear really means one gear. On an open country road, the Super Hawk has 3000 rpm and three gears (second, third, fourth) to work with. Try to be smooth, remember that valve float in third equals 80-plus, and keep entry speeds up. The doubleleading-shoe front drum is remarkably effective hauling down the 350-pound bike. Still, you don’t want to misread a comer, scrape off too much speed and call on the Super Hawk for an instant power burst. The CB77 accelerates rather than blasts. In the hands of expert rider/owner Finlayson, this Super Hawk runs very swiftly on these twisting country roads of southern Wisconsin. The pair can stay with first-rate riders on far more modem and faster motorcycles. And what does this mean? Despite its age, the Super Hawk hits the same Sanity Ceiling for Public Roads observed by fast, experienced riders on contemporary machines. Finlayson’s friends at the Sprecher Tap could vouch for that.

the apostle oakes

Images of Bob Oakes flickered through my mind that afternoon. At Sprecher’s my eyes absently scanned the long bar, half expecting to see Junior Sprecher serving up a Budweiser to Oakes, as though my faded recollections from other times at other taverns would somehow conjure up Oakes from an empty barstool. It couldn’t. Oakes died years ago. In the early Sixties, Bob was the Honda manager of BergPearson’s Sporting Goods in Madison. Oakes possessed a fire-plug stature, piercing dark eyes, short black hair cropped into a flat-top and a chiseled jaw cut square. Bob was charming and mean, passionate and opinionated, helpful and cantankerous, generous and irascible. You either loved him or hated him, first alternately and then simultaneously. Oakes was to Honda as St. Paul was to Christianity. Already a seasoned enthusiast, Bob had this dazzling motorcycling revelation which transformed him into a zealous apostle of Honda. Oakes had seen the light that was Honda’s special contribution: motorcycle technology at its best combined with manufacturing technology at its best. That special gift made Honda’s 50cc four-strokes inexpensive and tough. About $250 bought long-lasting, hasslefree amusement, and Oakes gloried in the amount of mischief and abuse the 50s could withstand. Furthermore, 50cc Hondas had an inviting innocence; they attracted “the right people” who were “the nicest people.” For him, though, that really wasn’t enough. Lots of nice

people were also dabblers whose next motorbike might be a canoe or shotgun. Oakes-the true believerwanted to recruit or create motorcycle enthusiasts who understood the technological superiority of Honda’s real motorcycles and grasped the importance of Honda’s ascendancy in Grand Prix racing. Oakes embraced roadracing and campaigned 50, 125 and 250cc machines. In his view, Honda had perfected direct genetic transfer from its GP racers on the Isle of Man to the bikes on his showroom floor. That was heady stuff. And contagious. Teenager Bruce Finlayson walked into Oakes’ domain and probably uttered a few magic words, like “Mike Hailwood” or “Jim Redman.” Finlayson recalls that Oakes seized the moment. “He unloaded this CB92R (a 125cc Twin) off the trailer and bumped it off. I heard those megaphones howl and watched the tach dance above 10 grand. I bought a Cl 10 (a 50cc sporty-styled motorcycle) and rode it around like a roadracer.” That autumn, Oakes put him on the CB92R at Mosport, Canada. Honda was serious about promoting racing. The company had scores of high-performance and roadracing accessories > for the CB72/CB77 series. Did you want clipons or a close-ratio gear cluster or a special racing saddle? Oakes could order it up. He figured Honda’s earnest support would elevate roadracing. Motorcycling would steadily lose its “unsavory elements,” and GP roadracing would become as glamorous and glitzy and classy here as in Europe. Its Grand Prix bikes might be Honda’s finest expression of high technology, but to Oakes the road-going Super Hawk was proof positive the commercial future belonged to Honda. Grudgingly, Oakes conceded that a few old-fashioned oil-leaking motorcycles had some beautifully crafted individual pieces and, well yes, the Honda did have untidy external seams on its gas tank and mufflers. Nevertheless, he’d insist, the Super Hawk was an engineering jewel and it too had some beautiful adornments, like its exquisite tachometer/speedometer with counter-rotating needles. Honda built Super Hawks until 1968. The CB77’s successor, the CB350 (1968-1973), was a better machine that sold in staggering numbers to an American market larger and hotter than ever. Sales figures aside, the CB350 didn’t-couldn’t-make a great technological leap forward in 1968 equivalent to the one the Super Hawk had made in 1961. Here a law of diminishing returns applied to innovation. But who could argue with Honda’s sales story? The company was wildly successful in the United States. Oakes doubted the staying power of Triumph and BSA, but for a while in the Sixties, the British prospered. Honda had fostered an expanding universe of motorcycle enthusiasts, and this extended the possibilities for everyone. If just a small scattering of exSuper Hawk owners decided to buy Triumph Twins, the impact on Triumph sales was extraordinary. To Oakes, forsaking a Super Hawk to buy a Triumph was heretical behavior. Didn’t these guys understand Honda’s mastery over cruddy foibles? Bob underestimated the limitations of selling on innovation. First, in the Sixties, Honda couldn’t act quickly, broadly and consistently enough to create products that would sell non-stop on innovation alone. Second, even if possible, such an approach was unlikely to succeed. In a fundamental

sense, selling on innovation was selling a new rider experience based on new technology. It never occurred to Honda partisans like Oakes that some Super Hawk customers might next seek a new experience based on Old School technology...and buy a Triumph Bonneville. There was something else, something very curious, that perplexed the Honda faithful like Oakes. In the Sixties, Honda became so successful that the public began calling all motorized two-wheelers “Hondas.” Short term, such overlapping identity is a hallmark of great success. But in the long haul, having a brand name become synonymous with a product is too much of a good thing. The name becomes generic; this, in turn, tends to cloud brand identity and to dilute specialness. Losing specialness and becoming common in an enthusiast field is perilous. Enthusiast buyers are elitist. “Just when you think they’re getting smart,” growled Oakes, “they do something dumb.” People bought British and European (and American) motorcycles because they weren ’t Hondas and they weren ’t Japanese. That appalled Oakes. He lived long enough, however, to see his prejudices vindicated. Old-fashioned cruddy motorcycles passed into history. The Super Hawk did prove to be the harbinger of Triumph and BSA’s eventual demise. When the Japanese Revolution at last forced change in the Seventies, the British needed motorcycle technology at its best and manufacturing technology at its best to survive. The old regimes had neither and collapsed. Later, Norton went down too. HarleyDavidson, victimized by lagging development and poor quality control, nearly failed while part of the AMF conglomerate. Revived by a management buy-out miracle, Harley maneuvered itself into post-modern motorcycling. The quaint old cruds were gone. I left the Sprecher Tap having never seen Oakes but knowing he’d been there. Now that the company is 50,1 wonder whether anyone at Honda knows how important to its success Oakes and other evangelists in America were. “Come here,” Bob commanded shortly after we met in 1963, “ride my Super Hawk and see what the future’s like.” Outside Sprecher’s, Finlayson was waiting. I warmed up the Super Hawk and flew away. □