Editor-on-Chief

UP FRONT

David Edwards

AROUND HERE, IT'S CALLED "PULLING A Peter Egan." Seems every six months or so our Editor-at-Large, who also writes for Road & Track magazine, reshuffles his garage to incorporate yet another interesting blue-chip car or motorcycle. This usually involves the selling off of a vehicle or two, and perhaps the assistance of the local loan officer. As you may have read in recent Leanings columns, Peter's latest acquisition is a sweet 1951 Vincent Black Shadow, financed by the sale of his Harley Road King and restored Porsche 356.

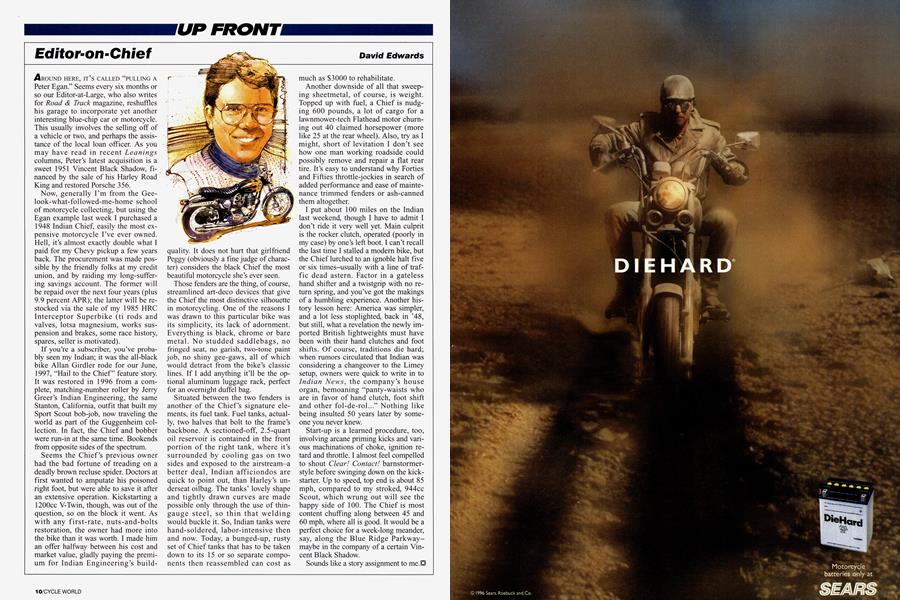

Now, generally I'm from the Geelook-what-followed-me-home school of motorcycle collecting, but using the Egan example last week I purchased a 1948 Indian Chief, easily the most ex pensive motorcycle I've ever owned. Hell, it's almost exactly double what I paid for my Chevy pickup a few years back. The procurement was made pos sible by the friendly folks at my credit union, and by raiding my long-suffer ing savings account. The former will be repaid over the next four years (plus 9.9 percent APR); the latter will be re stocked via the sale of my 1985 HRC Interceptor Superbike (ti rods and valves, lotsa magnesium, works sus pension and brakes, some race history, spares, seller is motivated).

If you're a subscriber, you've proba bly seen my Indian; it was the all-black bike Allan Girdler rode for our June, 1997, "Hail to the Chief" feature story. It was restored in 1996 from a com plete, matching-number roller by Jerry Greer's Indian Engineering, the same Stanton, California, outfit that built my Sport Scout bob-job, now traveling the world as part of the Guggenheim col lection. In fact, the Chief and bobber were run-in at the same time. Bookends from opposite sides of the spectrum.

Seems the Chief's previous owner had the bad fortune of treading on a deadly brown recluse spider. Doctors at first wanted to amputate his poisoned right foot, but were able to save it after an extensive operation. Kickstarting a 1200cc V-Twin, though, was out of the question, so on the block it went. As with any first-rate, nuts-and-bolts restoration, the owner had more into the bike than it was worth. I made him an offer halfway between his cost and market value, gladly paying the premi um for Indian Engineering's buildquality. It does not hurt that girlfriend Peggy (obviously a fine judge of charac ter) considers the black Chief the most beautiful motorcycle she's ever seen.

Those fenders are the thing, of course, streamlined art-deco devices that give the Chief the most distinctive silhouette in motorcycling. One of the reasons I was drawn to this particular bike was its simplicity, its lack of adornment. Everything is black, chrome or bare metal. No studded saddlebags, no fringed seat, no garish, two-tone paint job, no shiny gee-gaws, all of which would detract from the bike's classic lines. If I add anything it'll be the op tional aluminum luggage rack, perfect for an overnight duffel bag.

Situated between the two fenders is another of the Chief's signature ele ments, its fuel tank. Fuel tanks, actual ly, two halves that bolt to the frame's backbone. A sectioned-off, 2.5-quart oil reservoir is contained in the front portion of the right tank, where it's surrounded by cooling gas on two sides and exposed to the airstream-a better deal, Indian afficiondos are quick to point out, than Harley's un derseat oilbag. The tanks' lovely shape and tightly drawn curves are made possible only through the use of thingauge steel, so thin that welding would buckle it. So, Indian tanks were hand-soldered, labor-intensive then and now. Today, a bunged-up, rusty set of Chief tanks that has to be taken down to its 15 or so separate compo nents then reassembled can cost as much as $3000 to rehabilitate.

Another downside of all that sweep ing sheetmetal, of course, is weight. Topped up with fuel, a Chief is nudg ing 600 pounds, a lot of cargo for a lawnmower-tech Flathead motor churn ing out 40 claimed horsepower (more like 25 at the rear wheel). Also, try as I might, short of levitation I don't see how one man working roadside could possibly remove and repair a flat rear tire. It's easy to understand why Forties and Fifties throttle-jockies in search of added performance and ease of mainte nance trimmed fenders or ash-canned them altogether.

I put about 100 miles on the Indian last weekend, though I have to admit I don't ride it very well yet. Main culprit is the rocker clutch, operated (poorly in my case) by one's left boot. I can't recall the last time I stalled a modern bike, but the Chief lurched to an ignoble halt five or six times-usually with a line of traf fic dead astern. Factor in a gateless hand shifter and a twistgrip with no re turn spring, and you've got the makings of a humbling experience. Another his tory lesson here: America was simpler, and a lot less stoplighted, back in `48, but still, what a revelation the newly im ported British lightweights must have been with their hand clutches and foot shifts. Of course, traditions die hard; when rumors circulated that Indian was considering a changeover to the Limey setup, owners were quick to write in to Indian News, the company's house organ, bemoaning "panty-waists who are in favor of hand clutch, foot shift and other fol-de-rol..." Nothing like being insulted 50 years later by some one you never knew.

Start-up is a learned procedure, too, involving arcane priming kicks and vari ous machinations of choke, ignition re tard and throttle. I almost feel compelled to shout Clear! Contact! barnstormerstyle before swinging down on the kickstarter. Up to speed, top end is about 85 mph, compared to my stroked, 944cc Scout, which wrung out will see the happy side of 100. The Chief is most content chuffing along between 45 and 60 mph, where all is good. It would be a perfect choice for a week-long meander, say, along the Blue Ridge Parkwaymaybe in the company of a certain Vin cent Black Shadow. Sounds like a story assignment to me.~