ON THE TRAIL OF MARCO POLO

THERE IS AN ARCHAIC REGULATION AT WEST POINT that says a cadet shall not own a horse, a dog, or a moustache. Had the Powers That Be even suspected that I had a motorcycle that spring of 1932, it. too, would undoubtedly have been outlawed by the book of regulations. I had rented it from a shop in Highland Farms, a red Indian Scout that I practically lived on during the weekends from the time ice left the Hudson River.

Four years of schooling in tactics and logistics had impressed upon me that no individual, much less an army, can do anything near perfect the first try. Success demands practice, doing things over and over again—what the military calls “drv runs.” Thus, as the day drew closer for me to follow in the footsteps of the Venetian, I prepared by becoming completely at home on the vehicle I had chosen for my journey. The Indian was for training; I would buy another motorcycle for the trip when I got to France.

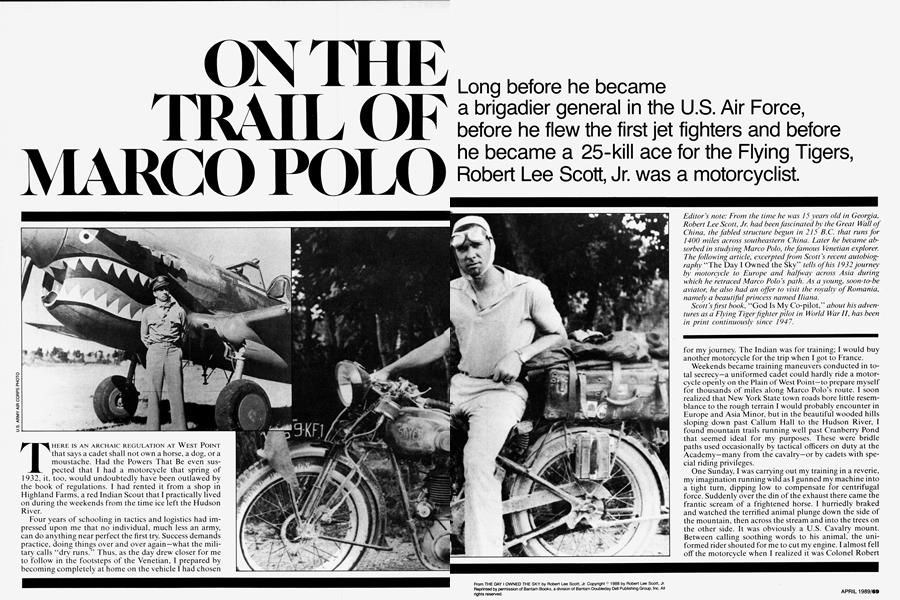

Long before he became a brigadier general in the U.S. Air Force, before he flew the first jet fighters and before he became a 25-kill ace for the Flying Tigers, Robert Lee Scott, Jr. was a motorcyclist.

Editor's note: From the time he was 15 years old in Georgia, Robert Lee Scott, Jr. had been fascinated by the Great Wall of China, the fabled structure begun in 215 B.C. that runs for 1400 miles across southeastern China. Later he became absorbed in studying Marco Polo, the famous Venetian explorer. The following article, excerpted from Scott's recent autobiography “The Day I Owned the Sky” tells of his 1932 journey by motorcycle to Europe and halfway across Asia during which he retraced Marco Polo's path. As a young, soon-to-be aviator, he also had an offer to visit the royalty of Romania, namely a beautiful princess named Iliana.

Scott's first book, “God Is My Co-pilot,” about his adventures as a Flying Tiger fighter pilot in World War II, has been in print continuously since 1947.

Weekends became training maneuvers conducted in total secrecy—a uniformed cadet could hardly ride a motorcycle openly on the Plain of West Point—to prepare myself for thousands of miles along Marco Polo’s route. I soon realized that New York State town roads bore little resemblance to the rough terrain I would probably encounter in Europe and Asia Minor, but in the beautiful wooded hills sloping down past Callum Hall to the Hudson River, I found mountain trails running well past Cranberry Pond that seemed ideal for my purposes. These were bridle paths used occasionally by tactical officers on duty at the Academy—many from the cavalry—or by cadets with special riding privileges.

One Sunday, I was carrying out my training in a reverie, my imagination running wild as I gunned my machine into a tight turn, dipping low to compensate for centrifugal force. Suddenly over the din of the exhaust there came the frantic scream of a frightened horse. I hurriedly braked and watched the terrified animal plunge down the side of the mountain, then across the stream and into the trees on the other side. It was obviously a U.S. Cavalry mount. Between calling soothing words to his animal, the uniformed rider shouted for me to cut my engine. I almost fell off the motorcycle when I realized it was Colonel Robert C. Richardson, the commandant of cadets.

From THE DAY I OWNED THE SKY by Robert Lee Scott, Jr. Copyright © 1988 by Robert Lee Scott, Jr. Reprinted by permission of Bantam Books, a division of Bantam Doubleday Dell Publishing Group, Inc. All rights reserved.

Fumbling to still my raving engine, I leaped from the machine, praying out loud that the “Com” could regain control before both he and his horse were killed. All my plans for a commission as a second lieutenant seemed to hang in the balance, but I dismissed these selfish thoughts and raced down the mountain, determined to reach the Com in time to be of some aid.

Colonel Richardson had everything safely under control long before I caught up with him, drenched to the waist after splashing through the creek. He sat in the saddle, speaking soothingly to the panting animal and rubbing its quivering neck. I stood there at attention, feeling more in a state of shock than the horse. At least, the thought came to me, the Com had not hit me with his riding crop. Finally, having attended to what every cavalryman considers his first duty, he turned his attention to me.

“Don’t you know, Mr. Scott,” he said calmly, “that the bridle paths are off limits to you, much less motorcycles?”

Only then did he dismount and slowly lead the quieted horse back across the stream and uphill to the path where my motorcycle lay. Ï tried to explain my fascination with the journeys of Marco Polo, my training for an attempt to retrace his route on motorcycle. I even discussed with him the enigma that so puzzled me. In all his journeys Marco Polo had never mentioned the Great Wall of China.

The Com listened intently as we walked our mounts down the bridle path. He asked about logistics. Could I make such a journey? Had I considered every angle? I kept waiting for him to revert to being the commandant, to quote some regulation prohibiting my summer plans, but such an announcement never came. When we reached the crossroads near the Cadet Chapel, he remounted to return to the stables. Before he turned away he told me to come see him at some convenient time the following week, saying that he had served as military attaché in Rome before his present duty assignment. Perhaps he might be able to tell me something to help me on my monumental journey.

“Good luck, Mr. Scott,” he concluded. “You represent something of an enigma yourself.”

Under the Norddeutscher Lloyd liner Europa anchored outside Cherbourg harbor, I could not believe I was truly on my way. From the firm of J. Bigard on the Rue de la Paix in Cherbourg, I bought a sparkling new Soyer motocyclette for which I would be in debt to the Bank of Highland Falls, New York, for many years, very proud that my signature as a newly commissioned Army second lieutenant had been all the collateral required. I was well aware that there was little left to cover even Spartan living expenses, and I worried about my written agreement with Monsieur Bigard. If I successfully piloted one single-cylinder Soyer motorcycle across France, over the Alps to Venice, all across Europe into Asia, then to the far end of Turkey where it met Persia and the Soviet Union, then returned all the way to France, and if said motorcycle was still serviceable, he would buy it back at half price and I would have enough francs to pay my passage home.

If some catastrophe befell me or the machine during the roughly 24,000-kilometer—l 5,000-mile—trip, or if he refused to repurchase it after the journey, then I would have to work my way home on a slow freighter. Ordinarily that would be no problem, as I was a rated AB, or able-bodied seaman. This time it would mean that I would be late reporting for flight training at Randolph Field. Texas, so I laboriously translated the complicated agreement into English, with many references to my French dictionary, as Monsieur Bigard watched.

Early afternoon, June 14, 1932, I gave my motorcycle full throttle and was on my way over the Grande Route Nationale toward my long-awaited rendezvous with Marco Polo. The real thing at last, although the Soyer felt the same as the Indian Scout I had straddled during my training. I shrugged my shoulders into my leather jacket, relishing the rush of wind past my lowered goggles. If only the Com could see me now.

Equipment hung everywhere, from a camera over my shoulder to the suitcase on the baggage rack atop the rear mudguard. Below that was a small metal frame holding a gallon can of gasoline on each side of the wheel. On the front mudgard was my international license plate, K4885, and on either side were two small flags: One was always the Stars and Stripes; the other, the flag of the country through which I was passing. The goggles were the most important item because even a fly could damage an eye at one hundred kilometers per hour, and Lord knows I needed mine for my rendezvous with destiny as a fighter pilot!

I sped out of Normandy those five decades ago, pausing in Paris for a short night and a tank of essence. Dawn saw me clearing the Champs Élysées, past the famous junction that was known as l’Etoile, with the Arc de Triomphe, before heading for the Simplon Pass across the Alps into Italy. Then on by Lago Maggiore, Milano, Brescia, and Verona to Mestre, where I left my motorcycle and took a boat to my hotel in Venice. All that night along the Grand Canal I dreamed of Marco Polo; on just such a night in 1271 he had set out for Peking. My departure date along part of the same route was June 27, 1932.

For years I had studied the differing translations of Marco Polo’s Travels. The concensus was that Marco, his father, Niccolo, and his uncle Maffeo had begun their journey to Cathay by sailing from Venice to Acre in Asia Minor, then traveled northeast through Turkey to Mount Ararat. I had already been that route when I was a sailor in the Merchant Marine, so I was taking the liberty of following a land route the Polos might well have used on one of their later journeys. It would not be easy with the roads as they were then and the difficulties of crossing international boundaries. Bad as the dirt roads turned out to be, it was worse haggling with the red tape of all the customs controllers; at every border I had to prove I owned the motorcycle, write down its horsepower and cubic-centimeter displacement, and certify that I did not intend selling it in that country.

The Dalmatian coast of Y ugoslavia was beautiful, especially Ragusa (the ancient name of modern Dubrovnik), the “pearl of the Adriatic,” but under my wheels the dust of centuries had hardened into deep ruts that jarred me. Pulverized by heavy wagon wheels, it billowed up and blotted out the scenery as I raced through. Flies lurked in swarms over horse and cattle droppings, sometimes breaking the skin of exposed parts of my face as I drove into them at high speed.

By far the worst recollection I have—one that sets Yugoslavia apart from the rest of the world for me—is of the twenty-eight punctures I had in one day. Every one was from handmade horseshoe nails lurking in the powdery ruts. By the time I had repaired a dozen flats, I did not even bother to take the wheel off the tire, I merely pulled the part of the tube with the hole in it past the rim, cleaned the cut with gasoline, and applied my dry patch. I guess I became an expert after twenty but I cried when I had number twenty-eight. By the time I roared into Belgrade I was praying there would be fewer horses farther east.

To keep my sanity I began setting goals. Each day I would try to break the record of the mileage I had set the day before. Often I would continue to drive after dark to attain my quota of miles before finding lodging, and some nights I never found a place to stay. By the time I reached the Pindus Mountains the roads were so steep and rough I often had to push the motorcycle along. At least the punctures became fewer and after two days without a flat I no longer felt a prisoner of dust and horseshoe nails. Maybe the people here did not use nails as had the Croats, the Slovaks, and the Slovenes; whatever the reason, I breathed a prayer of thanks as I came into Salonika and found the route north through Bulgaria to Sofia.

Northeast on a good highway across the Danube was Bucharest, where I had an invitation to visit Her Royal Highness, Princess Iliana of Romania, but I saw from the map that Bucharest was north of any route Marco Polo would have taken in 127 l. I decided to save my visit to the court of Queen Marie for the return trip, and set course due east for the great city I always think of as Constantinople, no matter that my maps said Stamboul or Istanbul.

I crossed the Hellespont into Scutari and realized I had reached Asia on my motorcycle. There I wrote two postcards, one to my parents and the other to Colonel Richardson, the commandant of cadets whose horse I had almost scared to death on the bridle path above West Point. I spent just the single night in Constantinople, as I knew I would be back that way. Right then I set out for Ankara. Of course, all signs were in Turkish, and it was harder to tell where I was or where I was headed than it had been in Greece or Bulgaria. Before I knew it I had taken the wrong turn and arrived in Eskisehir. My error in navigation should have been evident long before, but the road was so good that I kept hoping until I knew without a doubt that the sun was in the wrong place. After that I navigated by the sun and stars, forgetting the impossible road signs. If I went many miles out of my way, I consoled myself with the knowledge that I was seeing interesting parts of the country, just as Marco Polo had centuries ago.

One very dark night I saw a sign saying ADANA in the beam of my headlight; recalling that Marco Polo had definitely passed there, I revved my motor and took that fork in the road. For a few miles I even tried to sing a happy song but the small road led nowhere, just seemed to ramble. My headlight began to fail.

Then I collided head-on with a flock of sheep, the worst accident of the entire journey. It happened when I began a turn and the headlight flickered off at the crucial moment.

I did not see the sheep until I was among them at forty miles per hour and there were bleating, leaping woolly bodies all around me. I could not even fall with my machine until the flock moved off in panic, when I tumbled to the ground and had more of them run over me.

Over the bells on the rams I heard a human voice, highpitched and sinister in Turkish. It belonged to a shepherd, who quickly realized I was not a predator and coaxed the sheep away so that I could stand. Fortunately, none of his animals appeared hurt by our encounter.

Studying my map by the erratic lamp, I gave up my plan to visit Adana and carefully returned to the fork where I had gone wrong. This time I took the route to Erzurum, indicated as many miles ahead by the map, and followed it to the first town. Daylight had arrived before I reached Sivas, where I located a mechanic by his sign of crossed tools. I slept all day and most of the night while he rewound the magneto. From then on, for thousands of miles, the headlamp never flickered again.

I reached Erzurum two days later, dead center on the trail of Marco Polo and closing in on Mount Ararat. The region turned out to be a military zone extending north and east to the Soviet border, and signs were now in Russian as well as Turkish. The mountain rose more than 16,000 feet and was snow-covered. At its base, I was at the end of Turkey and as far east as I was going to be able to follow Marco Polo that year—or for a good many years to come, as it turned out.

I had covered a thousand miles of Asia since crossing the Hellespont—all the way across Turkey over practically no roads at all. Moreover, I had made good nearly a third of the 7,700-mile trail of the Venetian. It had been fortythree days since I had thundered out of Cherbourg and my graduation leave would be close to finished by the time I could return. To the northeast lay Georgia—the Russian one—and to the southeast, Persia, the way I had to keep going someday. With one longing look I turned and started my return trip.

A visit to the capital of Romania made for an extra three hundred miles on the motorcycle and was the most interesting part of the trip. Though I failed to see the princess, the invitation she had written in Romanian proved to be most valid—I was treated like a visiting potentate for the hour I remained at the palace. As I look at the photograph of me astride that motorcycle in the summer of 1932, I know I surely looked too arrogant and unpresentable to have been received by royalty; it was probably for the best that the queen and her daughter were away at the summer palace on the Black Sea.

From Bucharest to Budapest the route was long and hard and high. I crossed the Transylvanian Alps, so wild in places I caught myself searching for the castle of Dracula. There were over seven hundred miles of twisting switchbacks among the mountains, though the scenery was worth the detour. The rest of my journey passed without incident—only a few flat tires along the Danube to Germany—but nothing could have fazed me after Yugoslavia and Turkey. Fifty-nine days after purchasing my shiny new motorcycle from Monsieur Bigard, I surrendered it to him caked with dust, dented from sheep, its paint sandblasted away—definitely travel-worn but still running. Without a murmur he lived up to his agreement and bought it back for half what I had paid, and I sighed with relief because I now had enough money to buy a ticket on the Bremen. I could hardly keep a straight face as he gave me the money; inexperienced in the world of commerce as I might be, surely I had taken advantage of this Frenchman.

After purchasing my ticket I returned to the motorcycle shop to pick up my baggage, and perhaps for a fond last look at my trusty Soyer. When I reached the showroom on the Rue de la Paix, such a crowd of people had gathered that I wondered if there had been an accident or fire. Making my way through the mob, I discovered a motorcycle causing the commotion. It took me a long time to recognize it; I never would have except for the familiar international license number K-4885 on the mudguard. What a metamorphosis! Cleaned, divested of accumulated road film, tar, grease, dust, and bugs mashed into it at a hundred Ks per hour; washed and polished to perfection and sporting new tires, it glistened under a large placard. I translated it with the help of my dictionary:

“This thoroughly tested, well broken-in motorcycle presented for special sale, recently piloted across Europe and Asia by an audacious American!”

But the asking price was more than I had paid for it new! Now I understood why Monsieur Bigard had smiled as he gave me just enough francs for my passage to the United States. No longer could I go home thinking I had shown Yankee business acumen at its best. From that day I never was going to think I had outmaneuvered a Frenchman.

The Bremen had me in New York in four days. After a visit to Georgia, I set out for Randolph Field on the road that truly was mine.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Up Front

Up FrontSo Many Curves, So Little Time

April 1989 By David Edwards -

At Large

At LargeSilver Wing For A Silver Eagle

April 1989 By Steven L. Thompson -

Leanings

LeaningsTen Percenters

April 1989 By Peter Egan -

Letters

LettersLetters

April 1989 -

Roundup

RoundupHonda's Spada: the Newest World Standard

April 1989 By David Edwards -

Roundup

RoundupHailwood Ducati For Sale: $19,000

April 1989