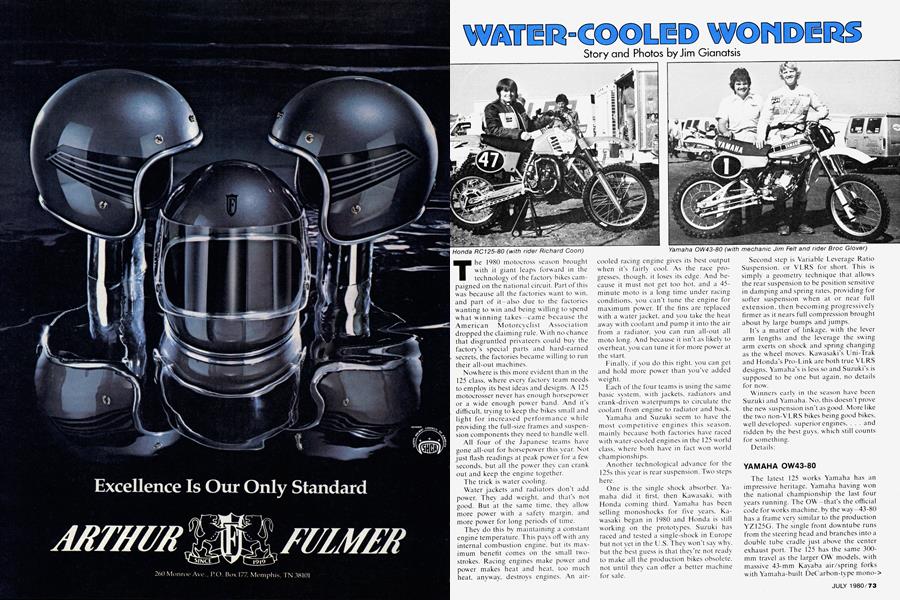

WATER-COOLED WONDERS

Jim Gianatsis

The 1980 motocross season brought with it giant leaps forward in the technology of the factory bikes campaigned on the national circuit. Part of this was because all the factories want to win. and part of it—also due to the factories wanting to win and being willing to spend what winning takes—came because the American Motorcyclist Association dropped the claiming rule. With no chance that disgruntled privateers could buy the factory's special parts and hard-earned secrets, the factories became willing to run their all-out machines.

Nowhere is this more evident than in the 125 class, where every factory team needs to employ its best ideas and designs. A 125 motocrosser never has enough horsepower or a wide enough power band. And it's difficult, trying to keep the bikes small and light for increased performance while providing the full-size frames and suspension components they need to handle well.

All four of the Japanese teams have gone all-out for horsepower this year. Not just flash readings at peak power for a few seconds, but all the power they can crank out and keep the engine together.

The trick is water cooling.

Water jackets and radiators don't add power. They add weight, and that s not good. But at the same time, they allow more power with a safety margin, and more power for long periods of time.

They do this by maintaining a constant engine temperature. This pays oft with any internal combustion engine, but its maximum benefit comes on the small twostrokes. Racing engines make power and power makes heat and heat, too much heat, anyway, destroys engines. An air-

cooled racing engine gives its best output when it’s fairly cool. As the race progresses, though, it loses its edge. And because it must not get too hot. and a 45minute moto is a long time under racing conditions, you can't tune the engine for maximum power. If the fins are replaced w ith a water jacket, and you take the heat away with coolant and pump it into the air from a radiator, you can run all-out all moto long. And because it isn’t as likely to overheat, you can tune it for more power at the start.

Finally, if you do this right, you can get and hold more power than you’ve added weight.

Each of the four teams is using the same basic system, with jackets, radiators and crank-driven w'aterpumps to circulate the coolant from engine to radiator and back.

Yamaha and Suzuki seem to have the most competitive engines this season, mainly because both factories have raced with water-cooled engines in the 125 world class, where both have in fact won world championships.

Another technological advance for the 125s this year is rear suspension. Two steps here.

One is the single shock absorber. Yamaha did it first, then Kawasaki, with Honda coming third. Yamaha has been selling monoshocks for five years. Kawasaki began in 1980 and Honda is still working on the prototypes. Suzuki has raced and tested a single-shock in Europe but not yet in the U.S. They won't say why, but the best guess is that they’re not ready to make all the production bikes obsolete, not until they can offer a better machine for sale.

Second step is Variable Leverage Ratio Suspension, or VLRS for short. This is simply a geometry technique that allows the rear suspension to be position sensitive in damping and spring rates, providing for softer suspension when at or near full extension, then becoming progressively firmer as it nears full compression brought about by large bumps and jumps.

It’s a matter of linkage, with the lever arm lengths and the leverage the swing arm exerts on shock and spring changing as the wheel moves. Kawasaki's Uni-Trak and Honda’s Pro-Link are both true VLRS designs, Yamaha’s is less so and Suzuki's is supposed to be one but again, no details for now.

Winners early in the season have been Suzuki and Yamaha. No. this doesn’t prove the new suspension isn't as good. More like the two non-VLRS bikes being good bikes, well developed, superior engines, . . . and ridden by the best guvs, which still counts for something.

Details:

YAMAHA OW43-80

The latest 125 works Yamaha has an impressive heritage. Yamaha having won the national championship the last four years running. The OW —that's the official code for works machine, by the way—43-80 has a frame very similar to the production YZ125G. The single front downtube runs from the steering head and branches into a double tube cradle just above the center exhaust port. The 125 has the same 300mm travel as the larger OW models, with massive 43-mm Kayaba air/spring forks with Yamaha-built DeCarbon-type mono-> shock plus reservoir, operating off’ a wellbraced aluminum swing arm. Front brake is a double leading shoe design of incredible stopping power. Because of the heavier suspension components the weight is increased slightly this year, to 182 lb. against 176 for the 1979 OW 125. (Yamaha takes pride in not making its bikes light bv resorting to titanium fittings the way the other teams do.)

The OW43's engine is extremely small and compact. A 36-mm Mikuni carburetor feeds a chrome-bore aluminum cylinder through reed valve induction. Transmission has six speeds, housed in sand-cast magnesium cases. The pump is driven off the left side of the crank and moves coolant through the cases, up through barrel and head to an aluminum radiator mounted on the triple clamps. The routing here is unique: Coolant goes through passages in the clamps, steering head and frame, to the engine and back, without hoses. No loose clamps, no risk of crash damage.

SUZUKI RA125-80

Suzuki’s reigning world champion RA (that's works bike, while RN is prototype and RM is production) is as refined as Yamaha's 125s. Yearly changes to the RA’s engine and chassis are less noticeable than on other bikes but then, it doesn't make sense to change a good thing. Like the Yamaha, the Suzuki gets big-bike suspension this year, including 43-mm Kayaba air/oil/spring forks built to Suzuki's specifications. and either Kayaba or Ohlins DeCarbon reservoir shocks, to provide 300 mm of wheel travel. Suzuki likes to play with titanium so you can bet this bike weighs right at the AMA's 176-lb. legal minimum.

The water-cooled RA uses case reed valves and a 36-mm Mikuni carb. The cylinder probably uses a steel sleeve. The pump is driven from the right side of the magnesium engine cases, to the front downtube-mounted radiator a short distance away.

KAWASAKI KX125 SR-80

This is the first season for the all-new' KX works bike. In an attempt to make a machine that handles better than the others, Kawasaki has resorted to nothing less than a full-size motorcycle. The wheelbase is nearly 60 inches, wheel travel is 300 mm at both ends, and there are 43-mm Kayaba forks and a Kayaba-built DeCarbon reservoir coil-over shock worked by the UniTrak rear suspension. Weight is more than the others, with Kawasaki claiming I9l lb. dry, 209 lb. ready to race. The KX250 works bike also weighs 209 lb., so they almost have to be using the same basic machine with different engines. That means the water-cooled 125 engine weighs as much as the air-cooled 250.

Interesting. Kawasaki’s system is more or less a bolt-on kit. as coolant from the pump on the righthand side of the cases is circulated by hoses, outside the engine to the cylinder and head, then to the framemounted radiator. A 36-mm Mikuni (again) operates through a reed valve on the cylinder. The cylinder bore is plated with Kawasaki's Electro-Fusion. The six speed transmission is housed in production-based aluminum main cases with magnesium covers for clutch and ignition.

HONDA RC125-80

This is also the first year for Honda's water-cooled RC with Pro-Link single shock. The overall design is similar to Kawasaki’s, but the Honda seems more carefully thought out and offers some significant advantages. The Honda shock is upside-down, compared with the Kawasaki. and it fits directly between swing arm and frame, w hile the Kawasaki uses a rocker arm. The Honda design weighs less and is simpler. The shock itself, made by Showa or Kayaba. can be tuned for damping. spring pre-load and wheel travel with the shock in place, while the Kawasaki needs to come out for tuning. Honda forks are 39-mm Showas. and w heel travel—also again—is 300 mm.

Honda's water cooling is different. There are two pumps, one to move coolant from radiator to engine, the other from engine to radiator. And there are two radiators. each mounted outboard of the stanchion tube in front of the fuel tank, with shrouds to duct air away from the radiator’s back.

The engine is mostly magnesium, with a six-speed gearbox, the obligatory 36-mm Mikuni. reed valve induction and a chrome bore in an aluminum cylinder.

The RC125 abounds with technical innovation and is the most interesting of the works machines. That doesn’t mean it’s the best of the bunch, because it lacks the development time that’s helped the Yamahas and Suzukis. Nor does Honda have the development riders on the American team that are needed to sort the bikes out.

And that’s w hy the older designs, for the time being at least, are out front. E9