Double Life

A banker by profession, B.R. Nicholls was a Cycle World writer/photographer in the magazine’s formative years. Founding Editor Joe Parkhurst remembers the good times.

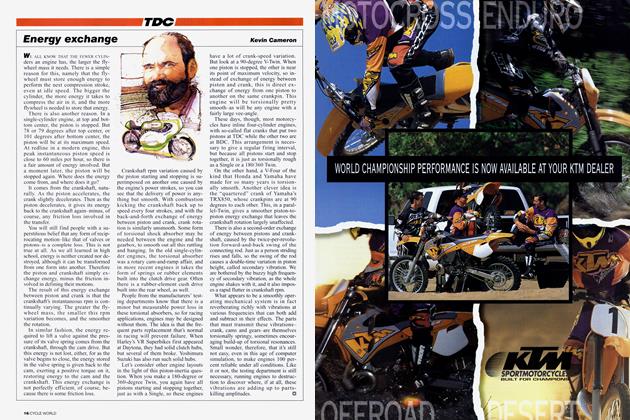

"MORNING," HE WOULD CHEERILY COMmand as we entered the stark white dining room of the Aragon Hotel on the Isle of Man. Most raised their heads from the engrossing task of devour ing a genuine English breakfast to say, "Mornin', Nick" or "Cheers, Nick."

Brian R. Nicholls was “Nick” to all who knew him, even the envious fellow journalists who knew he had a sweetheart deal with an American magazine that lavished money on him. At least that’s how it appeared to his peers, whose pay scale was far below that of Americans in the Sixties when the dollar was worth much more than today.

This endearing scene was only one of many played out during the times I spent with Nick on the Isle of Man during TT Week. Almost from the moment Cycle World began the metamorphosis from dream to reality, I was determined to find someone in England to write a column, cover motorcycle races and provide the best possible photography.

The Motor Cycle was Great Britain’s preeminent magazine at the time, so I telephoned the editor, Harry Louis, for his suggestion on someone who could write and supply photographs. Without hesitation, he replied, “Nick Nicholls.” A letter to Nick elicited an immediate response. Today, Nick remembers the enthusiasm in my letter-and how much I was willing to pay. It worked out to the equivalent of about sixpence (7 U.S. cents) a word, quite a lot in England for the time. After estimating the average number of words in a column, he rushed out and bought a new typewriter.

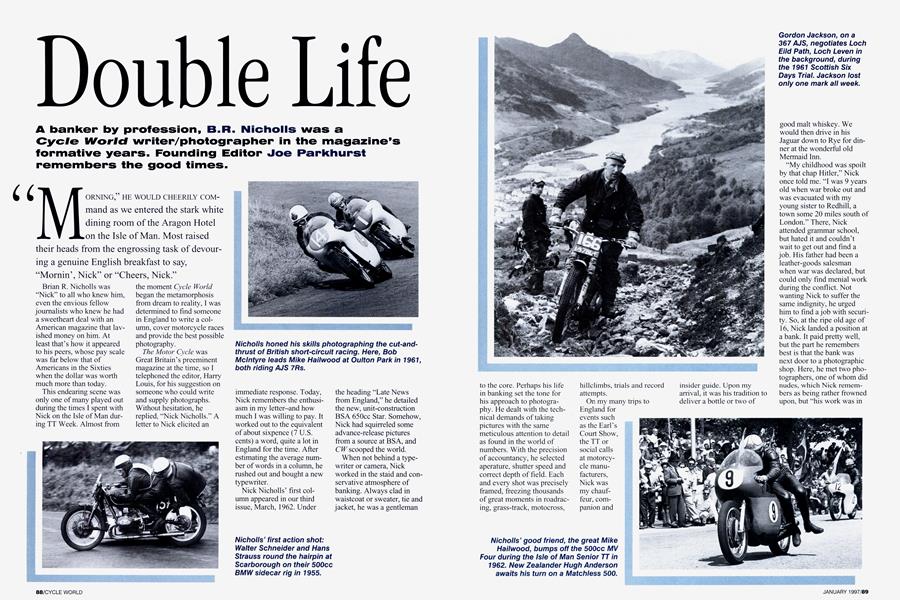

Nick Nicholls’ first column appeared in our third issue, March, 1962. Under the heading “Late News from England,” he detailed the new, unit-construction BSA 650cc Star. Somehow, Nick had squirreled some advance-release pictures from a source at BSA, and CW scooped the world.

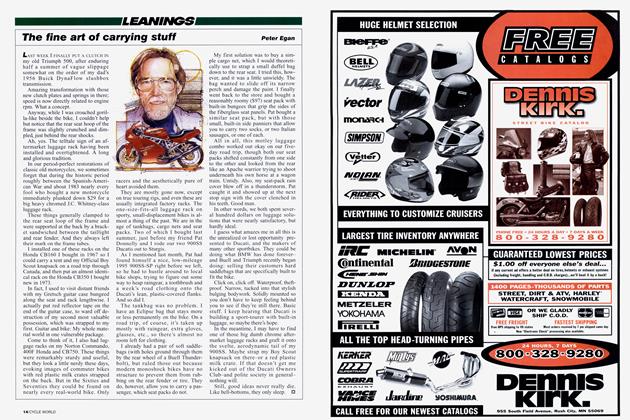

When not behind a typewriter or camera, Nick worked in the staid and conservative atmosphere of banking. Always clad in waistcoat or sweater, tie and jacket, he was a gentleman to the core. Perhaps his life in banking set the tone for his approach to photography. He dealt with the technical demands of taking pictures with the same meticulous attention to detail as found in the world of numbers. With the precision of accountancy, he selected aperature, shutter speed and correct depth of field. Each and every shot was precisely framed, freezing thousands of great moments in roadracing, grass-track, motocross, hillclimbs, trials and record attempts.

On my many trips to England for events such as the Earl’s Court Show, the TT or social calls at motorcycle manufacturers, Nick was my chauffeur, companion and insider guide. Upon my arrival, it was his tradition to deliver a bottle or two of good malt whiskey. We would then drive in his Jaguar down to Rye for dinner at the wonderful old Mermaid Inn.

“My childhood was spoilt by that chap Hitler,” Nick once told me. “I was 9 years old when war broke out and was evacuated with my young sister to Redhill, a town some 20 miles south of London.” There, Nick attended grammar school, but hated it and couldn’t wait to get out and find a job. His father had been a leather-goods salesman when war was declared, but could only find menial work during the conflict. Not wanting Nick to suffer the same indignity, he urged him to find a job with security. So, at the ripe old age of 16, Nick landed a position at a bank. It paid pretty well, but the part he remembers best is that the bank was next door to a photographic shop. Here, he met two photographers, one of whom did nudes, which Nick remembers as being rather frowned upon, but “his work was in the best of taste.” Nick blew his first wages on a 35mm Certo Dollina camera.

As required, he entered National Service joining the Royal Signal Corps in hopes of becoming a dispatch rider. Instead, the army tried to train him as a teleprinter mechanic. “For someone whose knowledge of electricity stops after changing the batteries in a torch (flashlight), it was a disaster,” he recalls with amusement. As things turned out, it was actually a blessing, because after two failing weeks, he was made a teleprinter operator, which led to his learning to type, a skill that would prove useful later in life.

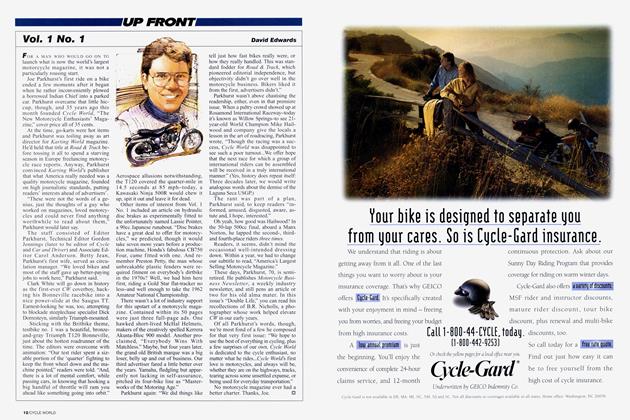

Following his stint in the service, he returned to banking and photography. The Dollina got junked, and he switched to a large-format Agfa folding camera, which he used to shoot his first motorcycle action photo-Walter Schneider on his BMW sidecar in the hairpin at the Scarborough circuit. Today, Nick says most of his early work was “rubbish,” but by this time he was truly bitten. Soon, every penny of his savings went for a used Leica M3 with an f2 Summieren lens that cost £60, then a small fortune. Nick began shooting his colleagues at the bank competing in soccer. Adding an Elmar 90mm f4 lens, he vowed not to buy any further equipment unless the camera could pay for itself.

In 1956, Nick shot an AJS 7R in action at Brands Hatch. The photo was good enough that Associated Motor Cycles (manufacturers of AJS) used it in an advertisement. That success brought interest from Cyril Quantrill, editor of Motor Cycle News, who asked Nick to cover all kinds of events for the paper. Hard work, because this meant that he had to process his own film to get prints on a train Sunday nights in order to make the Mondaymorning deadline for the weekly newspaper.

Finding that he could buy a new Nikon FE for what it cost to service the Leica, he quickly changed. The Nikon had a built-in exposure meter. Nick remembers “getting pictures not possible with the old ‘steam-driven’ Leica, where exposure had to be calculated with a hand-held Weston Master meter.” His reputation continued to grow.

Although the TT on the Isle Of Man was only one of many events Nick covered for Cycle World, it was here where his skill with logistics played well with photography. The TT in the early years was run over four days, beginning on Saturday with the Production Bike race. Monday saw the Sidecar and Lightweight 250 Internationals run. On Wednesday the 125 International ran first, followed by the Junior International. On Friday the 50cc International ran first, then the race everyone anxiously awaited, the Senior International.

Nick earned the sobriquet “Sergeant Major Nicholls” for the assiduous schedules he laid down in order to assure the week of TT racing would be covered from at least a dozen different vantage points around the 37mile course. If you were invited to ride with Nick around the island, his ironclad rules dictated that you appear at his car on time, be ready to jump out and run on command, and don’t lag or hold him up.

A typical day would call for shooting the start-finish line on Glencrutchery Road; then it was down to Quarter Bridge and a walk to Bradden Bridge; then over alternate roads to come in behind Union Mills, a very fast right-hand sweeper Nick loved to shoot. I liked it for the neat little pub.

Today, Nick’s archive of more than 20,000 images is especially valuable because when he began shooting there were no more than a half-dozen photographers covering the hotbed of British roadracing. But in the 1970s, he says, “Suddenly, the world and his wife had a camera. I suppose it was once Barry Sheene hit the heights that racing and the attendant photographers took off.”

Nick, now 65, spends time in the garden of his London home, and getting his negatives inventoried on a computer, a task he says will never be completed. He attends a few vintage events, and still shoots. In his life he owned only three bikes, finding the need for four wheels critical when carrying cameras. First came a secondhand 125cc BSA Bantam, which, he recalls, “would not

pull the skin off of a rice pudding.” He then bought a new 250 BSA Cl l-“Deluxe, with plunger rear suspension and four-speed box.” This was traded in on a “proper bike,” a new 350 AJS which he rates as his favorite vehicle, along with the Jag. Successful professional photographers have a signature work, one they are known by. An example is Volker Rauch’s capture of Mike Hailwood on the heeled-over Honda Six. Nick’s signature work is an unforgettable shot of Giacomo Agostini on the MV Agusta at Bray Hill during the 1970 TT. I was there, standing behind, thinking the shot would be impossible to catch. We’d heard about Ago’s antics on Bray Hill, and Nick wanted the shot. Elbows high, legs planted, camera in place, stooped forward, he looked like some kind of bird. Ago came and went so quickly I thought there was no way Nick got him. But he did. Ago made history that day, and Nick shared in the making.

About his own photography, Nick modestly says, “I suppose what we all seek to achieve in a photograph is to convey the atmosphere and action of the moment, something more than a mere record shot, which 99 percent seem to be.”

In the early Seventies, with Cycle World by that time a part of giant CBS Publishing, Nick balked at signing a release form created by the lawyers in New York. So B.R. Nicholls simply stopped working for Cycle World. He had never signed a formal working agreement, and I had never asked him to. We were good friends, so I understood his feelings, no matter how sad I was at losing his talent and precious store of work. It is wonderful for me to be a part of his fondly remembered past, the more than 10 years of devoted professionalism, the jolly good times.

Cheers, Nick.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue