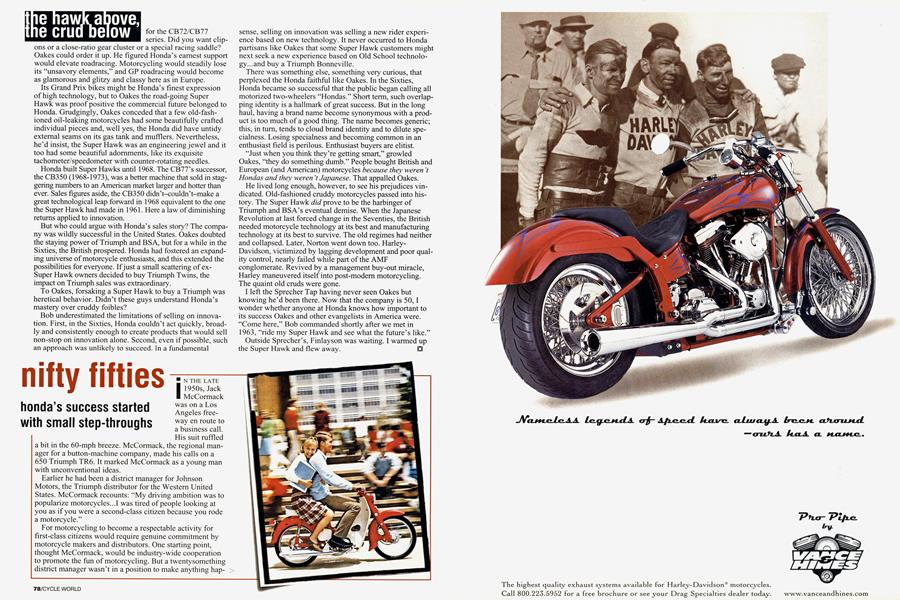

nifty fifties

honda's success started with small step-throughs

iN THE LATE 1950s, Jack McCormack was on a Los Angeles free way en route to a business call. His suit ruffled

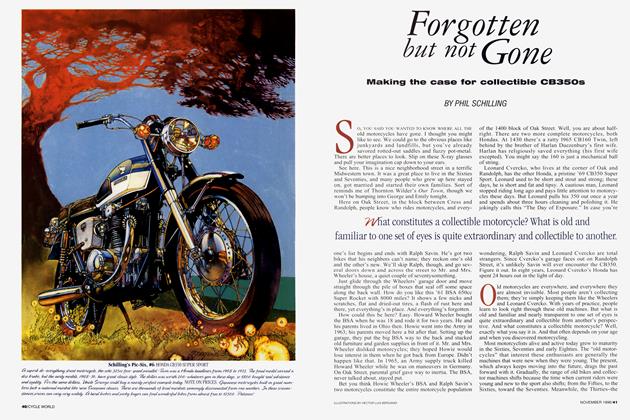

a bit in the 60-mph breeze. McCormack, the regional manager for a button-machine company, made his calls on a 650 Triumph TR6. It marked McCormack as a young man with unconventional ideas. Earlier he had been a district manager for Johnson Motors, the Triumph distributor for the Western United States. McCormack recounts: “My driving ambition was to popularize motorcycles...I was tired of people looking at you as if you were a second-class citizen because you rode a motorcycle.” For motorcycling to become a respectable activity for first-class citizens would require genuine commitment by motorcycle makers and distributors. One starting point, thought McCormack, would be industry-wide cooperation to promote the fun of motorcycling. But a twentysomething district manager wasn’t in a position to make anything happen. "I could never get anybody interested," McCormack says. "They were only interested in protecting their own little empires." McCormack's idea was too big for a small industry. Things would not change-perhaps they could not change. Maybe that was enough to make a guy want to go work for a button-machine company.

But motorcycles were always on McCormack’s mind. In 1959, he came across a fledgling company, little more than a storefront in downtown Los Angeles. At the time, American Honda Motor Corporation had but a handful of employees.

“I spent a lot of time looking at what they were trying to do, investigating their parts availability and seeing if they were in a position to support a U.S. operation,” McCormack remembers. “I finally talked to Mr. Kiyoshi Kawashima (later to succeed Soichiro Honda) about joining Honda and establishing their sales operation. Very early in 1960 I went to work for Honda as national sales manager.”

The machines impressed McCormack. “I was used to British equipment,” he recalls. “If you took an engine out of a Triumph frame, when you put it back in, you had to use drifts to line up the holes.”

Although the first Honda motorcycles had the basics-excellent engineering and wonderful quality-the firm’s “big” motorcycles (ranging from 150cc to 305cc) had pressed-steel frames, leading-link forks and alien looks. Honda would need different, full-scale motorcycles to appeal to American enthusiasts. Cue the Super Hawk.

Meantime, Honda had little four-stroke 50s to sell. These were the Cl00 Super Cub step-throughs, already successful as peoplemovers in the Asian market. The Japanese wanted to sell 50s in the United States as sensible, scooter-type transporters, too, but that concerned McCormack. “We couldn’t sell the step-through as a prime-mover here,” he says. “We had to sell it as something that was fun; a 50 wasn’t something that Americans would buy because they had to.”

What to do? “I can’t say I saw it immediately-that the 50s had immense sales possibilities,” McCormack remembers. “But it

suddenly occurred to me that there was an opportunity here to talk to the general public if I could get the ad budget.”

In setting up sales operations, McCormack and key Japanese executives decided to break American Honda franchises into two types: One would be full-line, 50cc and up; the second would be the “Fifty Franchise.” This was key, explains McCormack, “so we could get the 50s away from the black leather jacket image of motorcycling. In some places, we actually sold Honda 50s through barbershops and men’s stores. We did everything we could to keep from calling the Honda 50 a motorcycle. We called it a two-wheeled compact, a family fun vehicle-anything but a motorcycle.

We stayed away from talking about performance or about anything other than fun.”

McCormack projected total Honda sales of 15,000 units in 1961 (70 percent 50s), and asked for a $150,000 advertising budget. To appreciate the size of his ambitions, understand that the whole U.S. motorcycle industry sold about 50,000 units annually, and that McCormack’s advertising request was probably more than half the entire industry’s ad budget for the year.

McCormack got the money and spent it. “Our approach in 1961 was to take three ads out in Life magazine in the summer

months, in the western regional editions, and advertise Honda 50s as family fun vehicles,” he says. The ads cost $40,000 a pop. McCormack got greater mileage out of that money by using “pre-prints” of the ads for a direct-mail campaign to motorcycle and automobile dealers across the country. This displayed Honda’s audacious vision for the future, and helped build the dealer organization.

A couple of points should be underscored here. Honda’s first foray into general-interest magazines came almost a year before the much larger and more elaborate “You meet the nicest people on a Honda” campaign of 1962. The thrust into mass-circulation magazines with advertisements emphasizing clean-cut, middle-class fun originated with American Honda Motor Corporation, not an advertising agency. And this approach owed a great deal to McCormack’s earlier, unfulfilled ideas for the motorcycle industry while he was at Triumph.

The results were spectacular. In 1959, American Honda sold about 2500 units. In 1961, Honda moved 17,000 units-2000 beyond McCormack’s projection. In 1963, McCormack’s last year with Honda, sales had skyrocketed to roughly 90,000 units while the entire motorcycle market had reached about 150,000 units. Honda controlled 60-odd percent of a market that had expanded threefold in four years.

By 1963, McCormack was general manager of American Honda and widely regarded as the Magic Man of Motorcycling. Shortly thereafter, he would leave Honda and next organize U.S. Suzuki, putting that company on the American motorcycle map. In due course, other ventures ensued.

But McCormack will always be linked to Honda and its stunning first success in America. No one can say how motorcycling might have grown-or whether it would have burgeoned at all-without Honda, its Nifty Fifties or Jack McCormack. But we know what did happen, and how large the ideas of that young man, dressed in business suit and riding a 650 Triumph, eventually proved to be.

Big, very big. -Phil Schilling