Mecca in Birmingham

The Barber Motorsports Museum

PHIL SCHILLING

IT WAS BRITISH UNDERSTATEMENT AT ITS FINEST. BRIAN Slark is a guy who could stand at the epicenter of an 8.0-magnitude earthquake, with buildings falling and dust rising, and inquire, “Feel that tremor?” Slark, who was national service manager for the Norton Villiers Corporation back in the heady days of the Seventies, closed his fax message from the Barber Vintage Motorsports Museum with this line: “Phil, you should stop by this place sometime.”

Indeed.

The Barber Vintage Motorsports Museum, located in Birmingham, Alabama, has already assembled a world-class motorcycle collection. At this point, Barber has the best privately funded collection in the United States. You could argue, persuasively, that this is the best collection in the United States, period. “It’s pretty amazing,” opines Slark.

George Barber has reached this level quickly. He bought his first few bikes in 1988 and concentrated his efforts on motorcycles in 1991. He has built up an extraordinary array of bikes in a few years, created a vintage roadracing team, won eight national titles in AHRMA, run his historic racebikes in national and international exhibitions, and established a foundation to underpin the museum. The Barber operation has about 425 restored, new and/or original

motorcycles, 12 employees, display rooms, storage halls, restoration shop, library, machine shop, dyno room, race department quarters and another 175 unrestored motorcycles. Barber has accomplished this in six years. Don’t underestimate what he might do in the next six.

Of course, considerable resources support Barber’s enterprise (he owns one of the largest dairy operations in the South). But more impressive is the organization’s drive for excellence and its capacity to learn and grow. In the very beginning, for example, motorcycles were restored according to Barber’s personal tastes and standards of quality-and the result was over-restoration. Before long, the Barber organization understood the importance of research, historical accuracy and exact restoration.

George Barber came late to motorcycles, but he is a quick study. He refined his mission-from a pleasing personal assemblage to a collection of international motorcycles, significant to the worldwide sport and rarely seen in the United States. The museum has begun gathering milestone American motorcycles that will add to the richness and diversity of the collection and broaden its historical context. Thus, Barber started out as a casual collector, and then, through his interest, scholarship and vision, he became an enthusiastic student and patron of motorcycling.

Given the size and complexity of its collection, the Barber organization needs a number of specialists. Slark, restorerconsultant, has a molecular knowledge of British motorcycles, and his mastery in other areas is substantial. In the Fifties and Sixties, he worked in the AMC competition shop and as a road tester; later in the Sixties, Slark was BSA’s western service instructor for the Rocket 3; after his years with Norton Villiers, he ran his own marketing businesses. On the side, Slark has served as the Norton International Owners Association’s technical editor for 20 years, and he’s a trustee of AHRMA and its director of safety and tech. To

have Slark’s kind of cumulative knowledge, an individual almost has to grow up in an industry as an eyewitness to history.

Still, memory needs to be backstopped by erudition and research. The more you know, the more you

know how much more there is to know. So caution and humility come with expertise. Jeff Ray, Barber’s executive director, says, “You can’t know everything and carry it in your head. After we complete a bike, we always ask ourselves what we can do better, and how we can do that. Every year we get better at restoration. The first 90 percent of a restoration is easy, the next 5 is much more difficult, and the last 5 makes a museum-quality bike.”

As a buyer and negotiator, Ray concentrates on the very best bikes that turn up through research, discovery or solicitation. Barber recently bought a set of early American board-track racers that the previous owner perfected for 40 years. The bikes required nothing, and no one in the future is likely to know more about these bikes than the preceding owner. Ray points out that it’s less expensive to buy a totally correct restored bike or a perfect original example rather than restoring the bike on site.

Barber’s restoration and race-shop facilities are nevertheless busy places. Major collections often become galleries of mechanical statues that don’t run, and wouldn’t be run if they could. The Barber operation believes that motorcycles should be live objects, and therefore Barber runs some very special, exotic and rare machines in race events and exhibitions. To be sure, things like threeand four-cylinder works MV Agustas

are “priceless,” but in a fundamental way they can be pointless as mausoleum occupants. Barber believes people should see and hear them. To experience these live machines builds excitement and interest in historic motorcycles in ways statuary simply can’t.

Suppose a fancy MV racer breaks a connecting rod, allowing the untethered piston to mangle its combustion chamber. “You do what MV would have done,” says Slark, “you fix it.” Ray and Slark know that few individuals or organizations have both the commitment and resources to fix things like works MVs. The point isn’t how much trouble this is or how much it costs. The point is to keep running history running and to share that accomplishment with all who will come to see and listen.

Sometimes, as in the case of Paton (a tiny Italian marque that built roadracing bikes), the fix-it approach means doing the final development on an unfinished engineering project. The Barber Patons are faster and more reliable now than any Patons before. While most projects are less formidable than the Paton, the can-do spirit carries over. Jeff Ray: “You might need a special exhaust pipe and there aren’t any. Everyone uses the closest available replacement. You have to tell yourself that someone made this part in the first place. Find out how or figure it out and do what was done originally.”

In order to operate successfully, the Barber organization needs a far-flung network of contacts. Today, Barber’s vintage team only competes in selected events in the U.S. The present focus is on international events where, in addition to fielding its normal racebikes, the team exhibits and demonstrates its great historic racers. Last year, Barber sent an MV Four, a Paton and Mike Hailwood’s 1979 NCR Ducati to England’s post-TT Mallory Park event. Such international participation builds goodwill, credibility and ready access inside a worldwide collector community. This process has positive results beyond phone calls going through directly and getting attention. Since the Barber name is on everyone’s short list of real players, news of significant bikes for sale travels quickly to Birmingham.

The AJS Porcupine that appeared at the Rick Cole Auction at the Petersen Museum last March had been offered privately long before going on the block. Few people probably knew more than Slark and Ray about the bike, its origins and components. That’s precisely the value of accumulated experience, international access and credibility. The Barber organization determined what the bike was worth to the museum. Not enough for the seller. Unsold, the AJS went to auction, where the buyer (the Honda Museum, Japan) couldn’t complete the deal. Subsequent negotiations brought the AJS to Birmingham.

Most of the genuinely rare and exotic motorcycles in the world are already in the hands of knowledgeable collectors. When something quite special comes up-such as the Porcupine or a brand-new Britten-Ray has to ponder the options. Do you buy the Britten (one of the last two) and pass on several other bikes you’ve been considering? “It’s a matter of opportunity and supply,” says Ray. “Maybe you'll be able to buy those other bikes later, or very similar bikes. But you may only have one real opportunity to buy a new Britten. Do you want it, and how much do you want it?” Barber bought the Britten.

The beneficiaries of Barber’s enthusiasm and largess are American motorcyclists. Someone who cared only about American machines could spend a good day at the museum. Enthusiasts with more international interests should budget two or three days. In any event, one hour will dispel any provincial ideas about Birmingham being way out of the way. Far from a sideroad detour, the Barber Museum is the central plaza on motorcycling’s historic superhighway.

The Barber Vintage Motorsports Museum is open Wednesday-Friday, 9 a.m. to 3 p.m. (except holidays). For more information, contact Barber Vintage Motorsports, 512 28th St., Birmingham, AL 35233; 205/252-8079.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Up Front

Up FrontMade In Minnesota

July 1997 By David Edwards -

Leanings

LeaningsSwords of Damocles

July 1997 By Peter Egan -

TDC

TDCOut of the Weeds

July 1997 By Kevin Cameron -

Letters

LettersLetters

July 1997 -

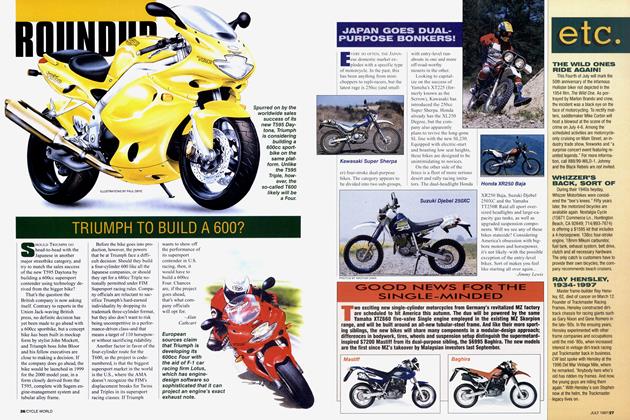

Roundup

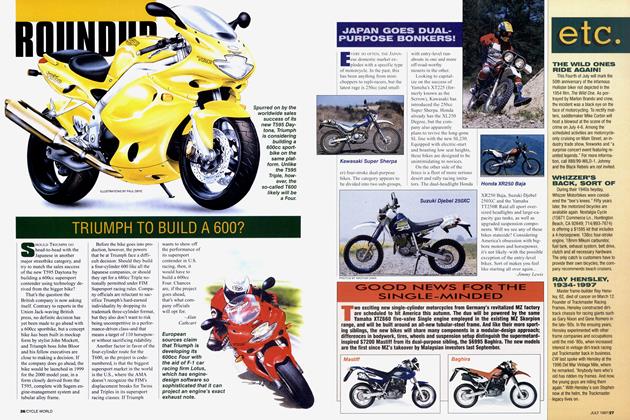

RoundupTriumph To Build A 600?

July 1997 By Alan Cathcart -

Roundup

RoundupJapan Goes Dual-Purpose Bonkers!

July 1997 By Jimmy Lewis