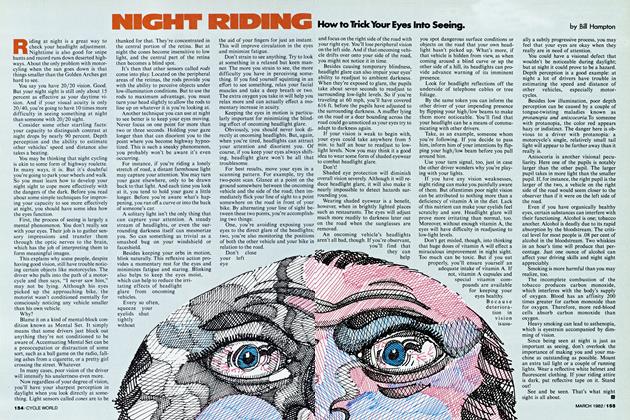

SUMMER SINGLE

TWO MEN AND A DUCATI MARK 3

PHIL SCHILLING

THE MODESTY THAT BECOMES A GENTLEMAN PREVENTS Mr. Finlayson from discussing his own heroic exploits aboard my Ducati Single some 30 years ago. I am not, however, so constrained, and I well remember that time when we were both young and immortal and did not know the meaning of stupid. Our lives were better for that ignorance.

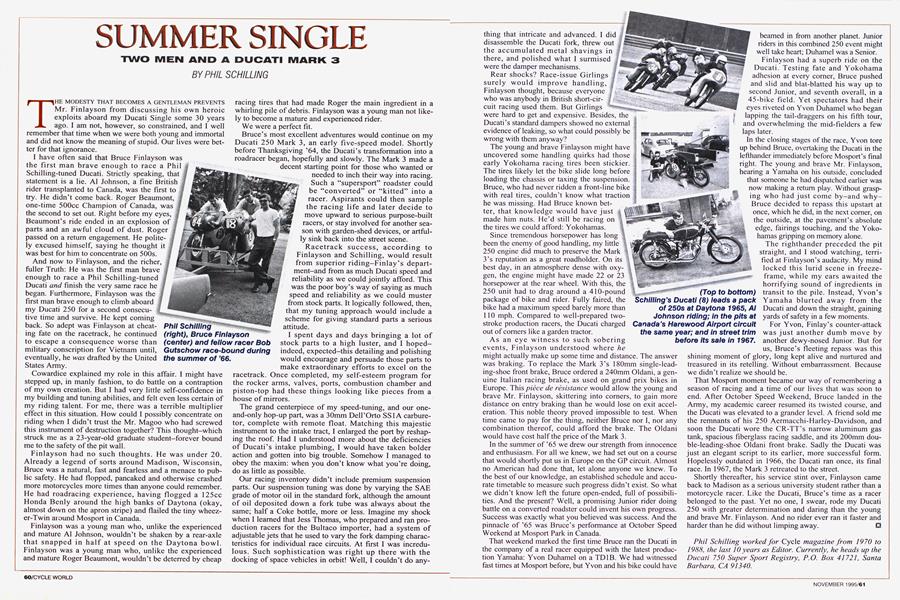

I have often said that Bruce Finlayson was the first man brave enough to race a Phil Schilling-tuned Ducati. Strictly speaking, that statement is a lie. Al Johnson, a fine British j rider transplanted to Canada, was the first to J~ try. He didn't come back. Roger Beaumont, J one-time 500cc Champion of Canada, was the second to set out. Right before my eyes, .j Beaumont's ride ended in an explosion of parts and an awful cloud of dust. Roger passed on a return engagement. He polite ly excused himself, saying he thought it was best for him to concentrate on 500s.

And now to Finlayson, and the richer, fuller Truth: He was the first man brave enough to race a Phil Schilling-tuned

Ducati and finish the very same race he began. Furthermore, Finlayson was the f first man brave enough to climb aboard my Ducati 250 for a second consecutive time and survive. He kept coming back. So adept was Finlayson at cheating fate on the racetrack, he continued to escape a consequence worse than military conscription for Vietnam until, eventually, he was drafted by the United States Army.

Cowardice explained my role in this affair. I might have stepped up, in manly fashion, to do battle on a contraption oí my own creation. But I had very little self-confidence in my building and tuning abilities, and felt even less certain of my riding talent. For me, there was a terrible multiplier effect in this situation. How could I possibly concentrate on riding when I didn’t trust the Mr. Magoo who had screwed this instrument of destruction together? This thought-which struck me as a 23-year-old graduate student-forever bound me to the safety of the pit wall.

Finlayson had no such thoughts. He was under 20. Already a legend of sorts around Madison, Wisconsin, Bruce was a natural, fast and fearless and a menace to public safety. He had flopped, pancaked and otherwise crashed more motorcycles more times than anyone could remember. He had roadracing experience, having flogged a 125cc Honda Benly around the high banks of Daytona (okay, almost down on the apron stripe) and flailed the tiny wheezer-Twin around Mosport in Canada.

Finlayson was a young man who, unlike the experienced and mature AÍ Johnson, wouldn’t be shaken by a rear-axle that snapped in half at speed on the Daytona bowl. Finlayson was a young man who, unlike the experienced and mature Roger Beaumont, wouldn’t be deterred by cheap

racing tires that had made Roger the main ingredient in a whirling pile of debris. Finlayson was a young man not likely to become a mature and experienced rider.

We were a perfect fit.

Bruce’s most excellent adventures would continue on my Ducati 250 Mark 3, an early five-speed model. Shortly before Thanksgiving ’64, the Ducati’s transformation into a roadracer began, hopefully and slowly. The Mark 3 made a decent starting point for those who wanted or needed to inch their way into racing. Such a “supersport” roadster could be “converted” or “kitted” into a racer. Aspirants could then sample the racing life and later decide to move upward to serious purpose-built racers, or stay involved for another season with garden-shed devices, or artfully sink back into the street scene.

Racetrack success, according to Finlayson and Schilling, would result from superior riding-Finlay’s department-and from as much Ducati speed and reliability as we could jointly afford. This was the poor boy’s way of saying as much speed and reliability as we could muster from stock parts. It logically followed, then, that my tuning approach would include a scheme for giving standard parts a serious attitude.

I spent days and days bringing a lot of stock parts to a high luster, and I hopedindeed, expected—this detailing and polishing would encourage and persuade those parts to make extraordinary efforts to excel on the

racetrack. Once completed, my self-esteem program for the rocker arms, valves, ports, combustion chamber and piston-top had these things looking like pieces from a house of mirrors.

The grand centerpiece of my speed-tuning, and our oneand-only hop-up part, was a 30mm Dell’Orto SSI A carburetor, complete with remote float. Matching this majestic instrument to the intake tract, I enlarged the port by reshaping the roof. Had I understood more about the deficiencies of Ducati’s intake plumbing, I would have taken bolder action and gotten into big trouble. Somehow I managed to obey the maxim: when you don’t know what you’re doing, do as little as possible.

Our racing inventory didn’t include premium suspension parts. Our suspension tuning was done by varying the SAE grade of motor oil in the standard fork, although the amount of oil deposited down a fork tube was always about the same; half a Coke bottle, more or less. Imagine my shock when I learned that Jess Thomas, who prepared and ran production racers for the Bultaco importer, had a system of adjustable jets that he used to vary the fork damping characteristics for individual race circuits. At first I was incredulous. Such sophistication was right up there with the docking of space vehicles in orbit! Well, I couldn’t do any-

thing that intricate and advanced. I did disassemble the Ducati fork, threw out the accumulated metal shavings in there, and polished what I surmised were the damper mechanisms.

Rear shocks? Race-issue Girlings surely would improve handling, j Finlayson thought, because everyone who was anybody in British short-circuit racing used them. But Girlings were hard to get and expensive. Besides, the Ducati’s standard dampers showed no external evidence of leaking, so what could possibly be wrong with them anyway?

The young and brave Finlayson might have uncovered some handling quirks had those early Yokohama racing tires been stickier.

The tires likely let the bike slide long before loading the chassis or taxing the suspension.

Bruce, who had never ridden a front-line bike with real tires, couldn’t know what traction he was missing. Had Bruce known better, that knowledge would have just made him nuts. He’d still be racing on the tires we could afford: Yokohamas.

Since tremendous horsepower has long been the enemy of good handling, my little 250 engine did much to preserve the Mark 3’s reputation as a great roadholder. On its best day, in an atmosphere dense with oxygen, the engine might have made 22 or 23 horsepower at the rear wheel. With this, the 250 unit had to drag around a 410-pound package of bike and rider. Fully faired, the bike had a maximum speed barely more than 110 mph. Compared to well-prepared twostroke production racers, the Ducati charged out of corners like a garden tractor.

As an eye witness to such sobering events, Finlayson understood where he might actually make up some time and distance. The answer was braking. To replace the Mark 3’s 180mm single-leading-shoc front brake, Bruce ordered a 240mm Oldani, a genuine Italian racing brake, as used on grand prix bikes in Europe. This pièce de résistance would allow the young and brave Mr. Finlayson, skittering into corners, to gain more distance on entry braking than he would lose on exit acceleration. This noble theory proved impossible to test. When time came to pay for the thing, neither Bruce nor I, nor any combination thereof, could afford the brake. The Oldani would have cost half the price of the Mark 3.

In the summer of ’65 we drew our strength from innocence and enthusiasm. For all we knew, we had set out on a course that would shortly put us in Europe on the GP circuit. Almost no American had done that, let alone anyone we knew. To the best of our knowledge, an established schedule and accurate timetable to measure such progress didn’t exist. So what we didn’t know left the future open-ended, full of possibilities. And the present? Well, a promising Junior rider doing battle on a converted roadster could invent his own progress. Success was exactly what you believed was success. And the pinnacle of ’65 was Bruce’s performance at October Speed Weekend at Mosport Park in Canada.

That weekend marked the first time Bruce ran the Ducati in the company of a real racer equipped with the latest production Yamaha: Yvon Duhamel on a TD1B. We had witnessed fast times at Mosport before, but Yvon and his bike could have

beamed in from another planet. Junior riders in this combined 250 event might well take heart; Duhamel was a Senior.

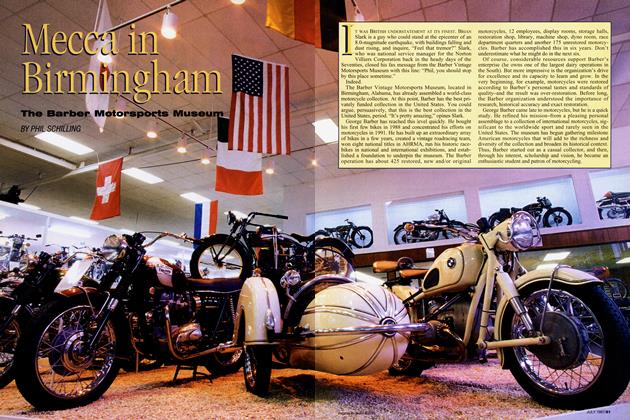

Finlayson had a superb ride on the Ducati. Testing fate and Yokohama adhesion at every corner, Bruce pushed and slid and blat-blatted his way up to second Junior, and seventh overall, in a 45-bike field. Yet spectators had their eyes riveted on Y von Duhamel who began lapping the tail-draggers on his fifth tour, and overwhelming the mid-fielders a few laps later.

In the closing stages of the race, Y von tore behind Bruce, overtaking the Ducati in the lefthander immediately before Mosport’s final right. The young and brave Mr. Finlayson, hearing a Yamaha on his outside, concluded that someone he had dispatched earlier was now making a return play. Without grasping who had just come by-and whyBruce decided to repass this upstart at once, which he did, in the next comer, on the outside, at the pavement’s absolute edge, fairings touching, and the Yokohamas gripping on memory alone.

The righthander preceded the pit straight, and I stood watching, terrified at Finlayson’s audacity. My mind locked this lurid scene in freezeframe, while my ears awaited the horrifying sound of ingredients in transit to the pile. Instead, Yvon’s Yamaha blurted away from the Ducati and down the straight, gaining yards of safety in a few moments.

For Yvon, Finlay’s counter-attack was just another dumb move by another dewy-nosed Junior. But for us, Bruce’s fleeting repass was this

shining moment of glory, long kept alive and nurtured and treasured in its retelling. Without embarrassment. Because we didn’t realize we should be.

That Mosport moment became our way of remembering a season of racing and a time of our lives that was soon to end. After October Speed Weekend, Bruce landed in the Army, my academic career resumed its twisted course, and the Ducati was elevated to a grander level. A friend sold me the remnants of his 250 Aermacchi-Harley-Davidson, and soon the Ducati wore the CR-TT’s narrow aluminum gas tank, spacious fiberglass racing saddle, and its 200mm double-leading-shoe Oldani front brake. Sadly the Ducati was just an elegant script to its earlier, more successful form. Hopelessly outdated in 1966, the Ducati ran once, its final race. In 1967, the Mark 3 retreated to the street.

Shortly thereafter, his service stint over, Finlayson came back to Madison as a serious university student rather than a motorcycle racer. Like the Ducati, Bruce’s time as a racer belonged to the past. Yet no one, I swear, rode my Ducati 250 with greater determination and daring than the young and brave Mr. Finlayson. And no rider ever ran it faster and harder than he did without limping away. □

Phil Schilling worked for Cycle magazine from 1970 to 1988, the last 10 years as Editor. Currently, he heads up the Ducati 750 Super Sport Registry, P.O. Box 41721, Santa Barbara, CA 91340.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Up Front

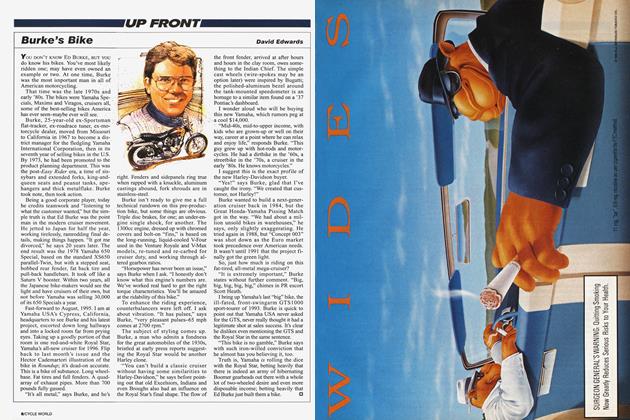

Up FrontBurke's Bike

November 1995 By David Edwards -

Leanings

LeaningsCafe Racing

November 1995 By Peter Egan -

TDC

TDCExtremes

November 1995 By Kevin Cameron -

Letters

LettersLetters

November 1995 -

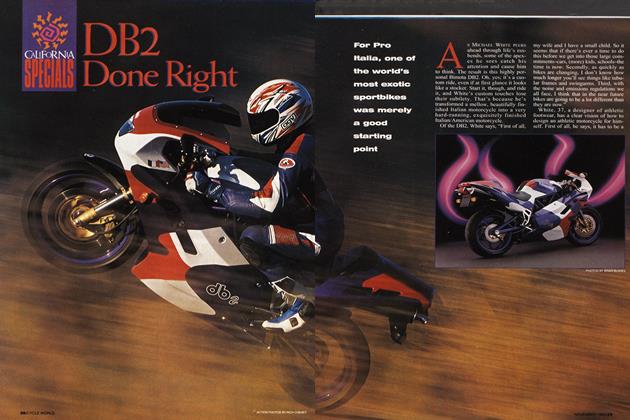

Special Section

Special SectionCalifornia Specials

November 1995 By Jon F. Thompson -

California Specials

California SpecialsDb2 Done Right

November 1995 By Jon F. Thompson