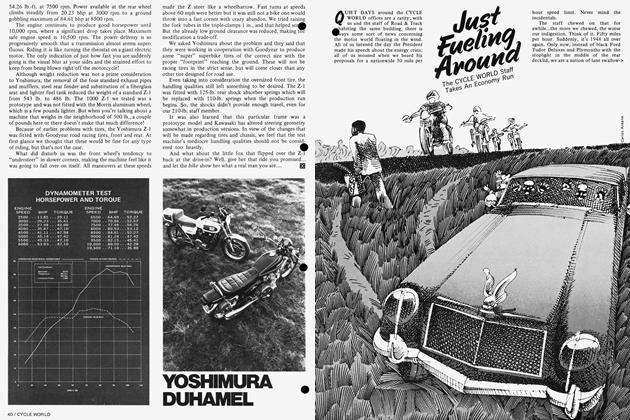

The Strut of Speed

Forget what the history books say, Ducati was born in 1957 with Dr. T and his

PHIL SCHILLING

IF HE KNEW THEN WHAT HE KNOWS NOW... HE still would have done it.

Seven years and thousands of dollars ago, Alan Chalk began a journey that veered into an obsession. Innocently shopping for a restoration project, Chalk saw an old single-cylinder Ducati that had been hacked and modified into a dirtbike. It didn’t run, and had no immediate prospects for life.

The seller, a knowledgeable Ducati enthusiast, knew what this bike had been 35 years before. Its distinctive frame and rare Dell’Orto carburetor identified the bike as a 1957 Ducati 175 Sport.

Chalk recounts, “I initially had no idea of what I was looking at.” But he is a quick study. Shortly after parking the rolling basketcase in his garage, Chalk came to realize just how extraordinary the bike was: the first production-series overheadcamshaft Ducati built.

Before the arrival of Ingegnere Fabio Taglioni in 1954, Ducati’s two-wheeled products largely consisted of practical motorbikes and miniature motorcycles. Taglioni’s very first single-overhead-cam motorcycles debuted in 1955. Called Marianna Gran Sports, these were 100 and 125cc sportsracing motorcycles produced in tiny batches. Somewhat experimental, Marianna Gran Sports were all about getting ready to get ready. In contrast, the 175-Taglioni’s first complete commercial product-qualified as a serious, assembly-line motorcycle with a rationalized design intended tor mass production.

To Chalk, an engineer himself, this history mattered. The 175 was the genesis bike for nearly 30 years of Ducatis. The bevel-drive 175 Single begat the 200, 250, 350 and 450 Singles, and the beveldrive 750, 900 and 1000 Ducati V-Twins bore the genetic code found in the 175.

The 175 Sport has a special importance as first.

A first product-one without real commercial antecedents-has a total newness and novelty that later derivatives by definition lack. Though technically less refined than its successors, the 175 marks the spot where product history began. The bike embodies the earliest, purest and simplest expressions of a set of engineering ideas by a brilliant and singular individual whose design career spanned decades.

Heart of the 175 Sport was a die-cast aluminum-alloy 62.0 x 57.8mm Single. A towershaft and two sets of bevel gears drove the single-overhead camshaft that opened intake and exhaust valves (one each) via rocker arms. Giant hairpin springs closed the valves-Taglioni’s trademark desmodromics would have to wait ’til 1969. The 175 breathed in through the open bell-horn of a 22.5mm Dell’Orto carburetor, and a four-ring piston provided an 8.0:1 compression ratio. The pressed-together crankshaft, riding in ball bearings, carried a one-piece connecting rod with a bushed smallend and a roller-bearing big-end. Helical-cut gears handled the primary drive; the transmission had four speeds, standard practice for the period. A gearset in the right-side timing chest ran the low-pressure oil pump and ignition points.

A single front downtube and a long, curved backbone grasped the engine front and back, the frame using the engine cases as a stressed member. Suspension was made up of a straightforward telescopic fork and basic shocks. The drum brakes were huge (180mm front/160mm rear) and the tires narrow (2.50/2.75 x 18).

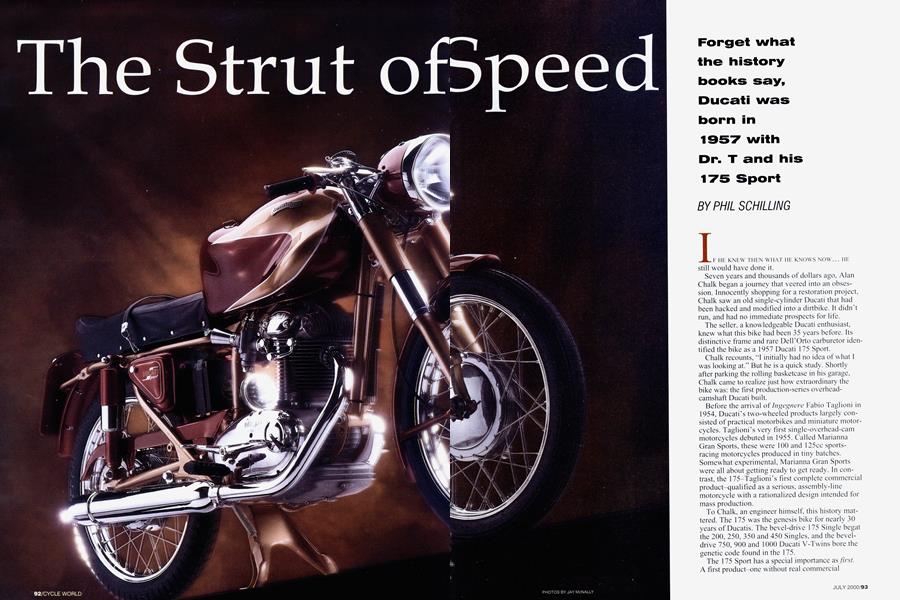

Two things gave the Sport an unmistakable identity. First, the striking engine looked like what it was, a stylized race-bred all-alloy engine for the street. Second, the flamboyant and convoluted "jellymold" gas tank was a sway-backed sculpted-steel biomorphic won der. It had arm recesses that allowed a crouched rider to fold in out of the airstream while gripping the stubby clip-on bars. Four eyelets on the tank secured a chin-pad for boy racers, or a utility bag for the faint-hearted.

The 175’s hard, tiny saddle had everything to do with racy appearance and nothing whatsoever with comfort. And for sheer visual shock, the Italians went over the top on color. Gloriously garish in metallic bronze and red-maroon, the Sport glowed like a neon peacock.

The bike had the stmt of speed, but without the swagger of intimidating power. The 10-cubic-inch engine delivered 14 Italian horsepower at 8000 rpm. Two-up and wide-open, the 175 could bellow out a swift 60 mph. With a solo rider more or less upright in the saddle and the engine at full-chat, the speedometer needle might rise to some figure equivalent to an actual 70 mph, an honorable velocity for a 175 roadster in 1957.

To approach the factory’s top-speed claim of 84 mph, though, the rider had to follow the directions given in some owner’s manuals-that is, remove the muffler and assume “the lowered race-type position.” Speeds nearing 80 mph required a small rider to be applied to the tank like a decal. Speeds beyond 80 demanded an imagination as bold as the bike’s color scheme.

When Ducati introduced this glamorous 175 at the Milan Show in December, 1956, Alan Chalk was 7 years old. Decades later, looking at his mangy dirtbike, Chalk faced a daunting restoration task. The only authentic, usable parts amounted to the frame and carburetor. He had never seen a complete-and-original 175 Ducati Sport, and no one he knew had either.

To complicate matters, production of the first 175cc overhead-cam models had been modest, so the survival rate after four decades promised to be something close to zero. In addition, Ducati only had an official American importer after 1957; consequently, any ’57 models would have arrived as random émigrés. Chalk understood the implications of all of this. He would have the pleasure of building his bike the old-fashioned way, piece by piece by piece.

Such a prospect would have most individuals pulling a strategic U-tum. The person who sold Chalk the bike had quickly decided the road to completion would be too long and uncertain. Others would have surely concurred, thinking. . .the project isn’t worth the anguish.. .and maybe this old 175 Single lacks great historical significance anyway.. .and what’s for dinner?

Chalk plunged on. “I guess I’m a sick man,” he jokes.

“I’m drawn to difficult tasks, I have a certain kind of compulsiveness to force my way through a hard task. Sometimes, it doesn’t pay off. Other times, it does. And in the case of this 175, it really paid off.”

Had Chalk started his project in the early 1980s, his mission would have been tougher still. But some thing happened, beginning in the mid-Eighties, that ..facilitated his quest. From that point, the number of Ducati histories and reference works steadily increased. Then the company’s renaissance in the Nineties spurred this rediscovery of Ducati’s past and the factory’s celebration of that history. This activity unearthed information, both text and photos, that had been lost or discarded or unpublished for years. While authors and publishers provided the best possible intelligence they could-and the new and rediscovered material was vital-much information lacked the specificity Chalk needed. He required detailed information about a single model built for a short period of time.

The key to that specific information was an illustrated parts catalog for the early 175 Sport. The book showed what parts should be used to assemble an authentic bike. The factory may not have built every 175 according to the book’s specifications, but inarguably many units matched up with the official document. Building a bike by the book simply obviates issues concerning a restoration’s “correctness.”

One example demonstrates how important the parts catalog was in resolving contradictions. Factory illustrations (and heavily doctored “photos”) of the 1957 Sport clearly show a smoothly curved exhaust pipe rather than the familiar and common pipe with two distinct bends. Was the curved pipe a prototype item? Or a first-run production example? Who knows? The catalog, however, establishes the double-bend pipe as a correct specification. The book’s line drawings show two different exhaust pipes, and both have distinct double bends. One pipe fits a single-muffler exhaust, the other complements a dual-muffler setup.

Chalk needed to create a critical mass of parts from which a bike could arise. He called every person who might direct his search or supply parts. His telephone expenses climbed to $2000 and expenses beyond. In short order he entered the scattered network of Ducati Single True Believers. Although some were secretive, most admired Chalk’s pluck for attempting the near impossible.

Here and there Chalk found caches of vital parts. A few individuals, he discovered, had once started assembling parts for their own 175 projects, which eventually languished for one reason or another. Once Chalk convinced these enthusiasts that he could and would complete a 175 Sport, they enlisted in his cause.

“They might not have been able to do it themselves,” observes Chalk, “but they wanted to see a 175 done, and they were willing to help make that happen.” Early on, Jonathan White supplied the vital parts book. Later. Daniel Lynn would complete the 175 engine by turning over parts he’d squirreled away over the years for himself. As time passed, the list of benefactors lengthened.

Routine frustrations still belonged exclusively to Chalk.

He vowed to wait until he had 95 percent of the parts in hand before starting the actual restoration work. Because he gathered while learning and learned while gathering, in the end Chalk misjudged his progress. “When I finally began working, I soon discovered that I was at 75 percent,” he says. To his surprise and dismay, he lacked, among other things, a good cylinder head. Until he found one months later, Chalk was flat stuck.

He persevered: “The engine was the most difficult thing to do. Money couldn’t buy a 175 cylinder head; I traded a jellymold tank for the head. With rare pieces, trading parts rather than paying money is the way business is done.”

Money is just money; often it has little value. Chalk points out, “If someone has a cylinder head or I have a special tank, getting money doesn’t work because that money just might not buy the next part you need.” In the kingdom of collector bikes, parts are the coin of the realm.

Today's information age makes compiling basic information easier. The Internet has become an excellent source for factory and distributor literature: Chalk located another early parts catalog in cyberspace. Now there’s a global network of Ducati enthusiasts and collectors. “To really make things work for you,” says Chalk, “you need to read and write Italian or Spanish or German or Japanese or whatever.”

In the end, he stresses, regardless of how you meet or know people, personal relationships are fundamental to serious undertakings. “It takes a lot of people contributing to do a difficult project,” Chalk says.

Chalk displays the 175 Sport in his living room. It’s fresh, ready to start, but he hasn’t run the bike because it contains parts that, at this point, are irreplaceable. For a runner,

Chalk recently completed a 1959 Ducati 200 Sport that also uses the basic jellymold tank. Though outwardly similar to the 175, the 200 is common by comparison.

The jellymold tank defined the Ducati 175 and 200 sports models. Unique and peculiar, the jellymold mimicked some early Ducati racing tanks. The raised rump contained a recessed well where a plastic gas cap spun on a threaded neck. The complex shape said expensive and special. Too bulbous to be truly beautiful, the tanks were nevertheless striking, unforgettable-and unequivocally Ducati.

Therein lies an important lesson in appearances. Had the 175 Sport been outfitted with an ordinary flat-paneled tank, high touring bars and a solo seat with a package rack behind, the motorcycle’s technical place as the original would be undiminished. But the shape of speed would have been gone. And with that perhaps the 175’s place in Alan Chalk’s living room.

Appearances count. Romance counts. Sometimes, life needs more than truth alone. It needs a little stmt.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Up Front

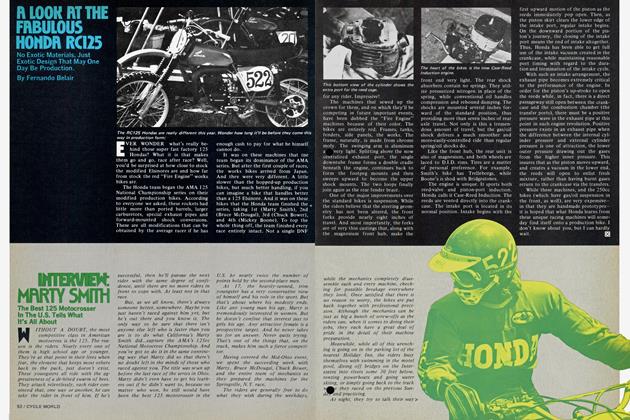

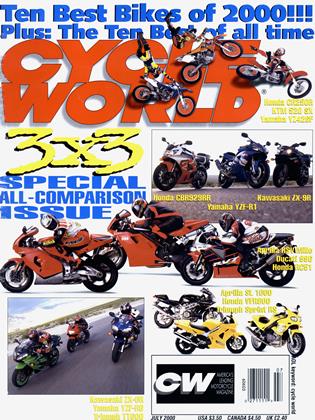

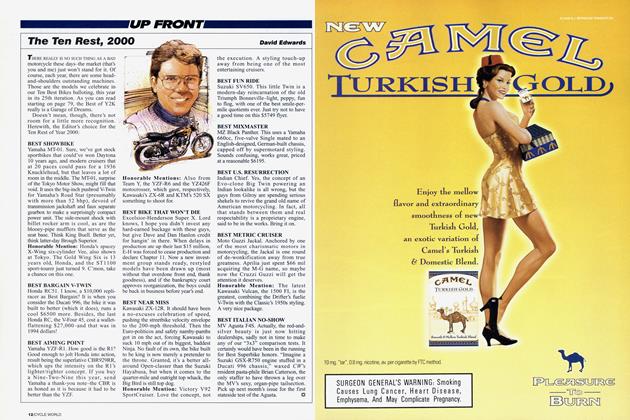

Up FrontThe Ten Rest, 2000

July 2000 By David Edwards -

Leanings

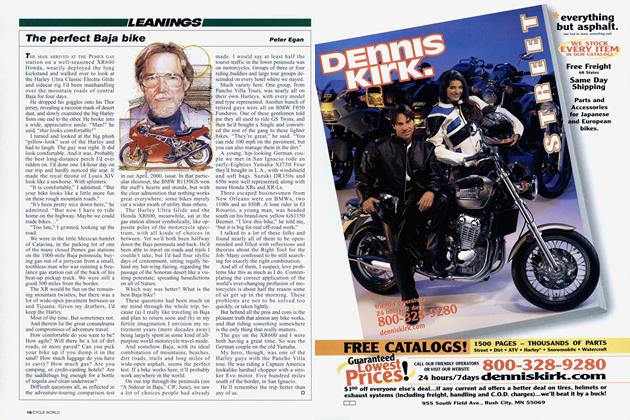

LeaningsThe Perfect Baja Bike

July 2000 By Peter Egan -

TDC

TDCCounting Cracks

July 2000 By Kevin Cameron -

Departments

DepartmentsHotshots

July 2000 -

Roundup

RoundupFriedel Münch Strikes Again

July 2000 By Kevin Cameron -

Roundup

RoundupAprilia Buys Moto Guzzi

July 2000 By Bruno De Prato