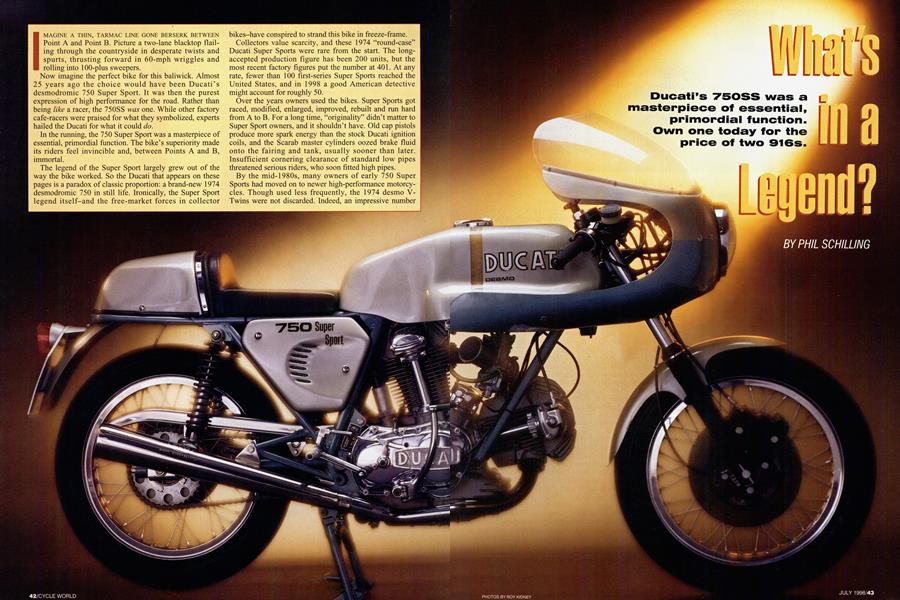

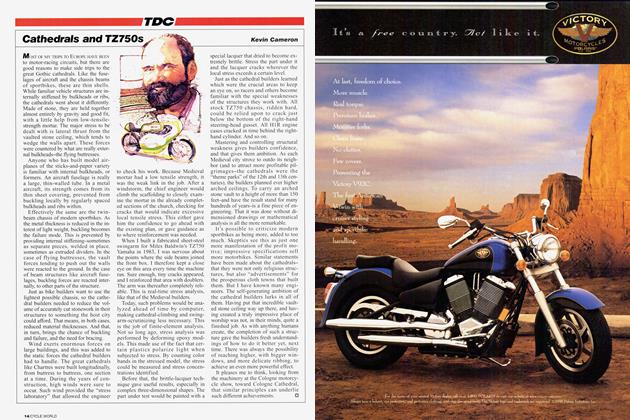

IMAGINE A THIN, TARMAC LINE GONE BERSERK BETWEEN Point A and Point B. Picture a two-lane blacktop flailing through the countryside in desperate twists and spurts, thrusting forward in 60-mph wriggles and rolling into 100-plus sweepers.

Now imagine the perfect bike for this baliwick. Almost 25 years ago the choice would have been Ducati's desmodromic 750 Super Sport. It was then the purest expression of high performance for the road. Rather than being like a racer, the 750SS was one. While other factory cafe-racers were praised for what they symbolized, experts hailed the Ducati for what it could do.

In the running, the 750 Super Sport was a masterpiece of essential, primordial function. The bike's superiority made its riders feel invincible and, between Points A and B, immortal.

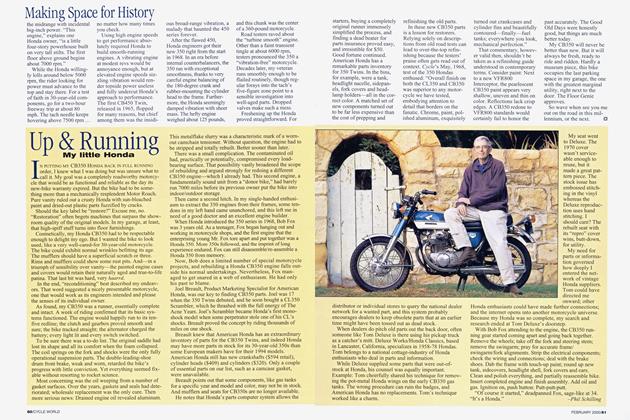

The legend of the Super Sport largely grew out of the way the bike worked. So the Ducati that appears on these pages is a paradox of classic proportion: a brand-new 1974 desmodromic 750 in still life. Ironically, the Super Sport legend itself-and the free-market forces in collector bikes-have conspired to strand this bike in freeze-frame.

Collectors value scarcity, and these 1974 "round-case" Ducati Super Sports were rare from the start. The long accepted production figure has been 200 units, but the most recent factory figures put the number at 401. At any rate, fewer than 100 first-series Super Sports reached the United States, and in 1998 a good American detective might account for roughly 50.

Over the years owners used the bikes. Super Sports got raced, modified, enlarged, improved, rebuilt and run hard from A to B. For a long time, "originality" didn't matter to Super Sport owners, and it shouldn't have. Old cap pistols produce more spark energy than the stock Ducati ignition coils, and the Scarab master cylinders oozed brake fluid onto the fairing and tank, usually sooner than later. Insufficient cornering clearance of standard low pipes threatened serious riders, who soon fitted high pipes.

By the mid-1980s, many owners of early 750 Super Sports had moved on to newer high-performance motorcy des. Though used less frequently, the 1974 desmo V Twins were not discarded. Indeed, an impressive number of Super Sports remained in the hands of first or second owners for 10 years or longer. The bikes, though outdated, remained appealing rides. In such circumstances, interest in "restoration" grows.

What's in a Legend?

Ducati's 750SS was a masterpiece of essential, primordial function. Own one today for the price of two 916s.

PHIL SCHILLING

When legendary motorcy cles are at the leading edge of high performance, those bikes undergo modifications to improve their performance. Get rid of those Italian coils! Long after the motorcycles have fallen off the leading edge, those improvements, seemingly so pivotal at an earlier point, become unim portant. From a longer perspective such improvements appear marginal.

Thus, a new objective emerges: getting the bike back in its original form. "Stock" becomes the watch word because the only universal standard for correctness are the original factory specifica tions. Consequently, the search begins for cap-pistol coils.

Retracing the path back to stock is nearly impossible after 20 years. Many original parts can't be sourced, matching the colors and time-aging of factory paint is just unfea sible, and a hundred other details make the return-trip to stock uncertain. The fit and finish of brandnew Super Sports were secondor third-rate in 1974, and trying to equal Ducati's levels of imperfection challenges painters and platers and fabricators. Over-restoration is so easy because original was so bad.

Today, most 1974 Ducati 750 Super Sports have been restored to some degree. Only a handful of 750 desmos sur vive intact in original, unblemished condition. At least two machines are showroom-new, making them the nearest of all, and the most correct.

Rarity was, and is, important to value. Had Ducati built 5000 examples of the 750 Super Sport, dozens would still be in their crates, and well-preserved examples would be com monplace. Supply would rule: Anyone who casually wanted to own a 750SS could have one.

But Ducati built so few 1974 750 desmos that demand rules today. In this context the bike's legend is crucial to value. The legend actually drives the demand for the bikes, and eventually the legend keeps enlarging the demand for a small fixed number of bikes.

Over time, the 750SS legend has grown beyond just the way the bike works. The functional prowess of an outdated bike cannot frilly explain the power and endurance of its legend. Something more is going on. - -

Special elements in the Ducati story fortify the potency and longevity of the 750 Super Sport legend. Subtract any one of these elements and both the Ducati story and the 750SS legend would be seriously diminished.

Taglioni: It will never be possible to talk about Ferrari without talking about Enzo Ferrari. In the same way, Ingegnere Fabio Taglioni is permanently embedded into the Ducati story. Practically every Ducati motorcycle built from the late 1950s into the mid-1980s bears his engineering stamp.

Taglioni put a face on Ducati. He burst onto the scene as the brilliant young engineer; in the 1970s, he was the wiz ard; and in his later years, he became the grand old master.

Very early, the cult of Tag lioni began. In the late Fifties, with one or two exceptions, Ducati could not afford star riders. Taglioni, the masterful engineer, filled this vacuumjournalists wrote about him and his engineering technolo gy. While many Italian lead ers in business and tech nology displayed neon egos, Taglioni was gracious, gener ous, soft spoken and revered. By the time Ducati's V Twins arrived in the United States in the early 1970s, Taglioni was the company's most widely recognized figure. With the success of the V Twins, American motorcycle journals soon popularized Taglioni by fashioning the "Dr. T" persona.

With Taglioni as the foundation piece, journalists could easily. write about long tradition, consistent engineering and enduring concepts at Ducati. Real individuals, with person alities and human longings, created Ducatis.

Without Taglioni, a parade of short-serving and faceless engineers might have swept through Ducati year after year. Without Taglioni, the great tale of the mighty wizard and his small, faithful coterie would not exist. Taglioni is essential to everything-the bikes, the legend, the whole lot.

Desmodromics: Taglioni `s desmodromic valve-actuation system caught the popular imagination of roadracing enthu siasts in the late 1950s. The system elaborated on a normal double-overhead-camshaft design by adding a third, center camshaft with forked rocker arms to close the valves.

When Taglioni devised his springless system in the mid 195 Os, desmo actuation allowed Ducati ` s single-cylinder two-valve 125cc Grand Prix engines to rev higher by accu rately controlling the valves at high rpm, and so preventing valves from colliding. The central advantage was improved mechanical reliability at very high engine speeds.

Any technological advantage of the desmo system was very short-lived, but desmodromics had been enshrined. In its way, the desmo was a conceptually perfect system for non-engineering enthusiasts to grasp. In a simple diagram anyone would see how this mechanical system worked and how this clever arrangement could-apparently-constitute superior technology.

Had Taglioni and Ducati dropped the desmo layout in 1959, then the system would have become a passing foot note, much like Mercedes-Benz's 1954-55 desmo experi mentation. Taglioni & Company persisted, built some desmo production-racer Singles in the mid-Sixties, and introduced the four-lobe single-overhead-camshaft desmo system on production 250/350/450 Singles in the late 1960s. The intriguing desmo idea, just as powerful as ever, got renewed.

By including desmodromics on the high-performance ver sions of the 1970s bevel-drive Twins, Ducati extended the desmo mystique. Ducati could have made valve-spring Super Sport models, and in fact, the highest performance 250cc production Singles of the 1960s had been valve-spring Mark III and Mach I models. But in 1974 Ducati elected to make high performance and desmodromics synonymous. That, in turn, made the first 750 Super Sports quite special, and inseparably connected to an almost mythical desmo past.

Underdog: For most of its early history, Ducati had been one of racing's most celebrated under dogs. The company, routinely in financial peril, could only manage limited and sporadic racing efforts that produced uneven results.

Against a pretty flat landscape of disappointments, Ducati's occasional successes rose like soaring monuments. By comparison, MV Agusta riders won 38 world championships, and that very regularity and repetitiveness served to grade those achieve ments into a high, featureless plateau of mar velous competence. A few pinnacles, clearly jutting up, can be easily remembered, and that worked to Ducati's benefit.

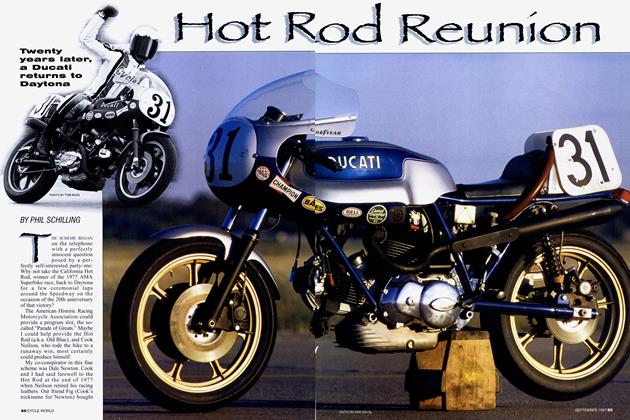

Until the 1990s, 10 fingers could count Ducati's finest moments. The big bevel-Twin desmodromics figured in three: 1) The smashing debut of 750 Desmos at the 1972 Imola "Daytona of Europe," where Paul Smart and Bruno Spaggiari finished 1-2; 2) Cook Neilson's 1977 Superbike win at Daytona with Cycle magazine's California Hot Rod; and 3) Mike Hailwood' s unforgettable victory at the Isle of Man in 1978. Take away those three triumphs and the 750SS legend shrinks in size from a large to a medium.

Maybe you could forget all the history, everything except the bike and the way it works. Certainly you'd have the core of the legend, but you'd miss its texture, depth and richness. For those things, you need the full drama. Remember that nothing succeeds like a great story. In motorcycling, Taglioni's desmodromic 750 Super Sport is proof of that.