Master Blast ERS

World's Ultimate Sportbike Shootout

DON CANET

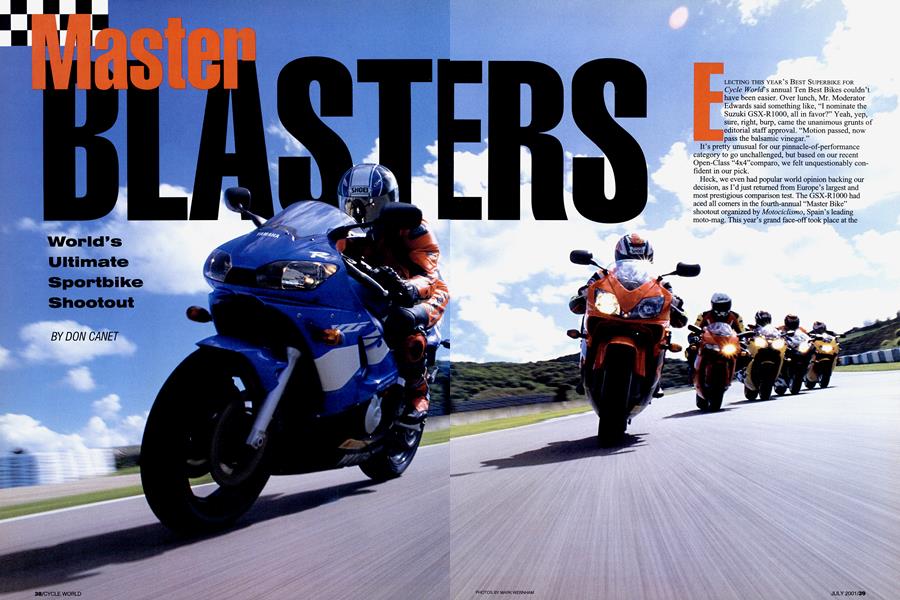

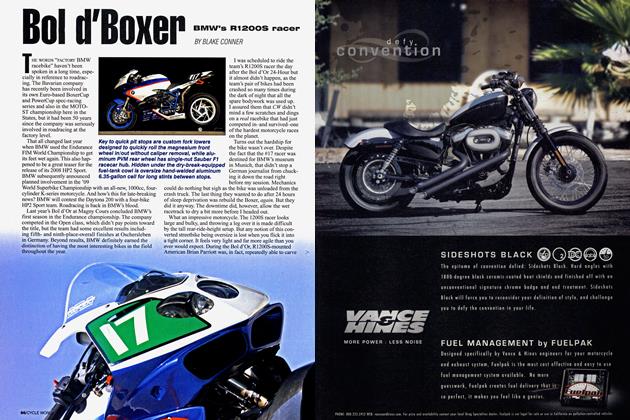

ELECTING THIS YEAR’S BEST SUPERBIKE FOR Cycle World's annual Ten Best Bikes couldn’t have been easier. Over lunch, Mr. Moderator Edwards said something like, “I nominate the Suzuki GSX-R1000, all in favor?” Yeah, yep, sure, right, burp, came the unanimous grunts of editorial staff approval. “Motion passed, now pass the balsamic vinegar.” It’s pretty unusual for our pinnacle-of-performance category to go unchallenged, but based on our recent Open-Class “4x4”comparo, we felt unquestionably confident in our pick. Heck, we even had popular world opinion backing our decision, as I’d just returned from Europe’s largest and most prestigious comparison test. The GSX-R1000 had aced all comers in the fourth-annual “Master Bike” shootout organized by Motociclismo, Spain’s leading moto-mag. This year’s grand face-off took place at the Circuito de Jerez, a GP track located in Spain’s southern-most region, chosen for its reliable weather and world-class facilities. CW was one of eight international magazines on hand in a joint quest to determine the year’s Ultimate Sportbike.

This three-day feast on 17 tasty bikes at a fantastic track located in the land of sherry promised to be a sportbiker’s buffet of epic proportions. Machines were split into three main categories, with the winner of each group advancing to a final round to determine the overall victor: The “Master Bike!”

Largest of the groups was “Supersport,” consisting of the Ducati 748 R, Honda CBR600F4 Sport (our F4i), Kawasaki ZX-6R, Suzuki GSX-R600, Triumph TT600 and Yamaha YZF-R6. Next came “Superbike,” which comprised the Aprilia RSV Mille R, Ducati 996 S, Honda VTR1000 SP-1 (our RC51), MV Agusta F4 750 S and Suzuki GSX-R750. “Open Class” contestants were the Honda CBR900RR Fireblade (our 929), Kawasaki ZX-9R, Suzuki GSX-R1000 and Yamaha YZF-R1. For good measure, Ducati’s new limited-production-and all but unbuyable-996 R and a Hondapowered Japanese special called the TSR AC91M made up a special “Reference” category not eligible for the final.

It all sounded like way too much fun to qualify as a business stay, so upon landing in Madrid I marked the “pleasure” box on the Spanish customs card. A short hop on to Jerez and I met up with Mark Wemham, our photographer who flew in from England. It was late in the day as we pulled into the paddock to find the pit garage alive with activity. Ironically, the Pirelli truck had gotten a flat en route to the circuit. Pirelli men in red coveralls were busy busting beads while several others busted butt to get all the bikes rolling on fresh Supercorsa radiais in preparation for the following morning’s activities.

Along pit row, nine participating motorcycle brands occupied as many garage stalls filled with bikes, spares and toolboxes. Uniform-clad support crew dressed in corporate colors tended to the machines, lending the scene the look and feel of a professional race meeting.

A noisy garage down the way housed Motociclismo's dyno-hauled in from the home office in Madrid-where each bike was run to insure no cheaters entered the contest.

While no suspects were flagged, I noticed some inconsistencies with our own dyno results obtained in recent comparison tests. In Spain, the Honda F4 and Kawasaki ZX-6R both made more power than the Suzuki GSX-R600 or Yamaha YZF-R6. The GSX-R750 barely edged out the Honda VTR1000 and Ducati 996 S, while coming up slightly shy of Aprilia’s RSV Mille R. Hmmm. Well, at least the GSXR1000 stomped everyone’s rear-wheel output, laying down a withering 139 bhp, 11 more than its closest rival, Yamaha’s Rl.

Another garage had been converted into a makeshift studio, serving as base ops for a film crew documenting the entire event for the Master Bike IV video soon to be on sale in Europe. Photographers milled about the paddock making

use of the last traces of the setting sun. And Wemham? I found him loitering in the “Italian District,” where Aprilia, Ducati and MV Agusta had set up camp in neighboring stalls, He blurted out something poetic about a deepseated passion for Italian wine, women and machinery.. .then we headed for the trackside hotel’s bar. With 97 people enlisted, our group pretty much overran the Hotel La Cueva Park for the next four nights. Exchange of introductions quickly resulted in far too many faces and names to ever hope to pronounce or remember. Of the eight other pilots with whom I would be sharing the riding chores, some names I recognized, although not necessarily from the masthead of any magazine. Jürgen Fuchs was a ringer sent by Germany’s Motorrad. A veteran GP racer, Fuchs had chalked up fourth in the 1996 world championships riding an HB Honda NSR250 followed by a season in the prestigious 500cc class. Motorcyclist Japan had its own hired gun in Kei Nashimoto, a top-10 finisher in the past two Suzuka 8Hours. Multi-time Norwegian Supersport Champion Jerker Axelsson served as the surrogate wrist for Sweden’s Bike.

At least I wasn’t the only card-carrying journalist being fed to the wolves. Moto Journal (France), Moto Sprint (Italy) and Motociclismo (Portugal) each sent an on-staff editor to do the riding and writing. Our Spanish hosts had a pair of riders, one editorial-type plus dedicated test pilot Fernando Cristóbal, a seasoned racer and “Master Bike” master holding fast time in all previous editions of the test.

Motociclismo Editorial Director Augusto Moreno de Carlos presented a schedule detailing the plan of attack. We

were to ride each bike once, putting in two familiarization laps followed by four timed laps, then move on to the next bike in turn. Riders were issued a binder of survey sheets to be filled out after each session. Augusto’s final words encouraged a fast-yet-controlled pace. To keep the focus on the bike and not the individual rider’s time, lap timesrecorded by the official timekeepers who run the clocks during the Spanish GP-would remain secret until all 17 bikes had made the rounds. Then, only the four quickest riders would move on to the championship shootout. It wasn’t so much as said, but we all knew this was a race to be one of the Final Four.

Lap times weighed heavily on a bike’s overall ranking. Within each category, 45 points were awarded to the bike that set fast time among its peers. Each of the remaining bikes was allocated a lesser score based on the difference between its best time and the quickest for the category. A bike was also given five points when a rider set a personal best time (within the category) on it. If all nine riders went quickest on the same machine, then 45 points could be awarded. The survey sheets gave a 0-10 rating for such things as power delivery, throttle response, shifting action, stability in comers, nimbleness, suspension, grip, cornering clearance, brake performance, etc. Scores from all nine surveys were averaged together to determine the results for each bike.

I’ve never witnessed a magazine test anywhere near this scale. The logistics were mind-boggling and spent resources immense. The bikes burned through nearly 200 tires and 350 gallons of fuel, while the support personnel consumed nearly as many gallons of coffee.

A team of Spanish photographers shot upward of 18,000 frames of 35mm film during the event. This emphasis on images was quite evident, as the entire first day was an endless photo shoot from sun-up to sundown. Action Team, Motociclismo's promotional-events staff, had adorned the entire circuit and paddock with banners and erected a large inflatable pillar on pit road-it looked like a beer company promotional prop-all bearing the magazine’s logo. The fanfare reached new heights as flags of each participating nation were flown above their respective riders as we posed for yet another composition. Enthusiastic bands of Motociclismo readers were seated in the main-straight grandstand.

After a rain delay the following morning, bikes of the Supersport and Reference categories were placed single-file on pit lane for the start of the timed sessions. I was pleased to be assigned the user-friendly CBR600 for my first ride, as I would need to regain familiarity with the circuit, having only ridden there twice in the past. Back on pit road following two warm-up laps, we were released at 10-second intervals. As anticipated, the CBR felt solid and sure as I built speed with each passing lap. Then, out of nowhere, Cristóbal came strafing past on the brakes, his ZX-6R pulling a good bit of distance as we completed the final lap. Jeez! With the “Master

Bike” hotshoe starting 10 seconds behind me every session, I had good incentive to get with the PACQ, pronto!

The rotation also had me riding each bike immediately after Cristóbal. Eley, save a little tire for me, compadre! Of a shorter and stockier build, the Spanish rider effectively maximized cornering clearance with an exaggerated hangoff riding style. With so few laps to familiarize myself with each bike, I made a point to see what hard parts previous riders had touched down before heading onto the track. On some bikes, I found myself grounding items the Spanish ace hadn’t, even though-as I later leamed-his lap times were consistently 2 seconds per lap quicker. I was particularly surprised by the “Supersporf’-winning YZF-R6, which I found limited by an exhaust can that touched down solidly several times per lap and brakes that faded at the end of the track’s hardest braking zones. Fuchs and Cristóbal each found 3 seconds per lap that had eluded me. My personal best time in the category came on the Ducati 748 R, thanks to loads of cornering clearance, excellent stability and great feedback through the suspension.

Riding the Reference-class 996 R and TSR offered an eye-widening perspective of how docile a middleweight’s power delivery really is. The big-bore Ducati was trying to wheelie and headshake out of the same comers in which the Supersports had felt perfectly planted. The R’s rear tire was pretty scorched, too, making for some exciting moments during the limited number of laps. I focused on smooth throttle and brake inputs, as the controls were very sensitive compared to what I had ridden up to that point. The TSR, a CBR900-powered special out of Japan, offered a nice, stable chassis, strong brakes and broad spread of power, but lacked cornering clearance, evidenced by scrape marks halfway up its bulbous fairing.

There was plenty to get done on the last day, with the Superbike and Open Class categories’ elimination rounds to work through before moving on to the final. But first.. .more photos and video had to be shot. Bike-to-bike, car-to-bike, wheelie shots and rider interviews for the camera used up all the morning hours. As we began the timed sessions, the growing anticipation among the teams was painfully evident. A member of the Yamaha camp frequently strolled out to the pit wall with hands buried deep in pants pockets working a pair of concealed stopwatches. Elsewhere, an accusation that Aprilia was supplying its own “cheatercompound” tires-the Mille R uses Supercorsas as OEM fitment-thus gaining an unfair advantage, was quelled with confirmation that all bikes enjoyed equal footing. Turns out the Mille is an outstanding track bike, no deceit needed. When the lap times were tallied, the RSV narrowly beat out the GSX-R750 to take “Superbike” honors, joining the Yamaha R-6 in the run-off.

My most memorable ride of the afternoon came on the MV Agusta. The electric-smooth engine and close-ratio gearbox made beautiful music while the unflappable, rocksteady chassis allowed absurd banking angles through the comers. The brakes even proved flawless, MV having solved the chronic sponge syndrome we experienced with our testbike last year. Ah, a blissful experience that helps me love my work. But then my luck began to shift-quite literally...

Completing my first timed lap aboard the GSX-R750, my boot paws at the air when I try to shift up from second. The lever’s tang has gone missing, snapped off when I leaned deep through the final left-hander leading onto the pit straight. For me, the session is lost as repairs are made. I move on to the next bike, a CBR900RR, so as to not upset the rotation schedule.

I gave the Fireblade high marks for engine and handling, but a mediocre score for cornering clearance, having slewed sideways on the left engine cover a couple of times during the session, not to mention the pounding the exhaust canister took. The new Pirelli radiais really offer some impressive grip!

Paybacks are a bitch, they say, and the GSX-R1000 got me good for the abuse I’d laid on its little sister. Heading onto the track for the warm-up lap, I catch neutral on the upshift to second. Winggg! Winggg! The engine free-revs as two more attempts fail to engage the gear. I look down to see the linkage rod is bent, so I click back down to first and exit the track onto a service road leading back to the pits. Glancing down at the damaged shifter rather than where I was headed, I look up to see I’m on a collision course with a cornerworker platform positioned in the road. A reflex jink to the right saves my butt, but not my boot from being pinched between the bike and the steel structure.

Even though I don’t fall off, I’m finished, my left fibula splintered from the impact. I’m transported to the airport, booked on the next flight to Madrid to have surgery on my leg, missing out on the final hours of the test. Moments before boarding the Iberia jet, news comes that the GSXR1000, shift rod replaced, has broken the backs of its “Open Class”competition, and then gone on to just edge out the Aprilia RSV in the “Master Bike” final. Hey, the big Gixxer is good, no bones about it.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Up Front

Up FrontThe Ten Rest 2001

July 2001 By David Edwards -

Leanings

LeaningsThe World's Most Famous Bike?

July 2001 By Peter Egan -

TDC

TDCUp On the Roof

July 2001 By Kevin Cameron -

Departments

DepartmentsHotshots

July 2001 -

Roundup

RoundupExcelsior-Henderson Gone Forever?

July 2001 By Terry Fiedler, Tony Kennedy -

Roundup

RoundupSuzuki's Retro Big-Bangers

July 2001 By Matthew Miles