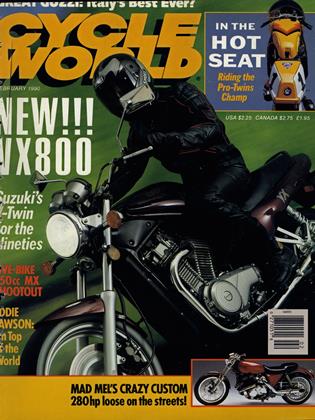

ONE OF A KIND

Riding the Twin that roared

ALAN CATHCART

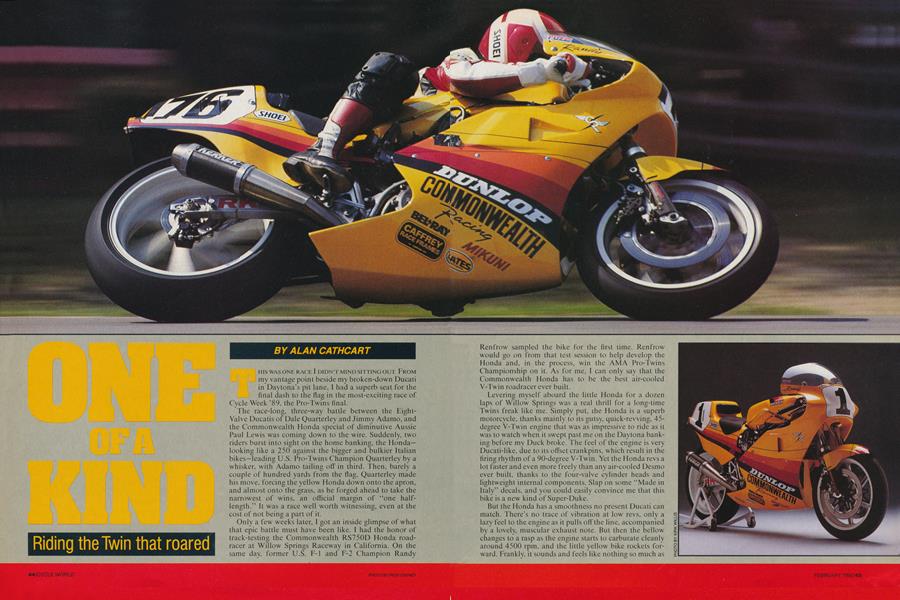

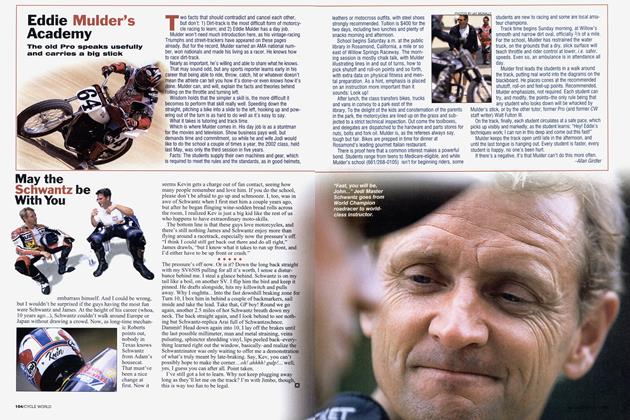

THIS WAS ONE RACE I DIDN'T MIND SITTING OUT. FROM my vantage point beside my broken-down Ducati in Daytona’s pit lane, I had a superb seat for the final dash to the flag in the most-exciting race of Cycle Week ’89, the Pro-Twins final.

The race-long, three-way battle between the Eight-Valve Ducatis of Dale Quarterley and Jimmy Adamo, and the Commonwealth Flonda special of diminutive Aussie Paul Lewis was coming down to the wire. Suddenly, two riders burst into sight on the home banking, the Honda— looking like a 250 against the bigger and bulkier Italian bikes—leading U.S. Pro-Twins Champion Quarterley by a whisker, with Adamo tailing off in third. Then, barely a couple of hundred yards from the flag, Quarterley made his move, forcing the yellow Flonda down onto the apron, and almost onto the grass, as he forged ahead to take the narrowest of wins, an official margin of “one halflength.” It was a race well worth witnessing, even at the cost of not being a part of it.

Only a few weeks later, I got an inside glimpse of what that epic battle must have been like. I had the honor of track-testing the Commonwealth RS750D Honda roadracer at Willow Springs Raceway in California. On the same day, former U.S. F-l and F-2 Champion Randy Renfrow sampled the bike for the first time. Renfrow would go on from that test session to help develop the Honda and, in the process, win the AMA Pro-Twins Championship on it. As for me, I can only say that the Commonwealth Honda has to be the best air-cooled V-Twin roadracer ever built.

Levering myself aboard the little Honda for a dozen laps of Willow Springs was a real thrill for a long-time Twins freak like me. Simply put, ihe Honda is a superb motorcycle, thanks mainly to its gutsy, quick-revving, 45degree V-Twin engine that was as impressive to ride as it was to watch when it swept past me on the Daytona banking before my Duck broke. The feel of the engine is very Ducati-like, due to its offset crankpins, which result in the firing rhythm of a 90-degree V-Twin. Yet the Honda revs a lot faster and even more freely than any air-cooled Desmo ever built, thanks to the four-valve cylinder heads and lightweight internal components. Slap on some “Made in Italy" decals, and you could easily convince me that this bike is a new kind of Super-Duke.

But the Honda has a smoothness no present Ducati can match. There’s no trace of vibration at low revs, only a lazy feel to the engine as it pulls off the line, accompanied by a lovely, muscular exhaust note. But then the bellow changes to a rasp as the engine starts to carbúrate cleanly around 4500 rpm. and the little yellow bike rockets forward. Frankly, it sounds and feels like nothing so much as half a V-Four Honda RVF750R works endurance racer, with the same ultra-flat torque curve. It hardly seems to matter which gear you approach a corner in. so long as you're operating in the 4500-to-9500-rpm range. This mile-wide powerband is especially handy if you need to hold a gear between turns to save a couple of unnecessary gear changes.

Fifth gear is very close to fourth, about 700 revs taller, and bottom gear is too low for racetrack use once on the move, though it. no doubt, accounts for the Honda’s lightning starts at races last year. The one-up, four-down gearchange is precise and butter-smooth; ditto the lightaction clutch. One can't fault the transmission in any way, though that’s what you would expect from the one-off assembly made specifically for this bike by HRC.

I did find some minor faults with the bike's handling, though. While the frame feels very stiff and handles the grip provided by the Dunlop radiais well, I don't honestly think it's right for the bike, at least not with someone of my greater size and less-aggressive riding technique aboard. For me, the front wheel pushed quite noticeably in turns, making high-speed sweepers difficult because I had to keep hauling the bike back into line while trying hard to stay on the gas. I'd say the reason for this is a combination of a relatively long. 57.5-inch wheelbase, a conservative-by two-stroke GP standards, at least-steering head angle of 24.5 degrees and less-than-ideal weight distribution.

The bike's owner, Martin Adams, and tuner. Ray Plumb were well aware of the slight handling problems of the machine, so it wasn’t surprising that not long after I rode it, they performed a host of changes. First, they installed a one-inch-shorter swingarm from a 1984 RS500 so the bike would steer more quickly. Then the RS500 fork was replaced with a works front end from Bubba Shobert’s Superbike. The internal damping of the new fork remains the same as that on the RS assembly, but the fork tubes themselves are a bit longer. Also, the front brakes from the Superbike, featuring 1 Omm-larger disc rotors, were fitted. The brakes on bike when I rode it were fantastic. Built to stop an RS500 GP Triple weighing around 80 pounds less than the RS750, they are undoubtedly the best brakes I have ever sampled on any Twin. No wonder Fewis was able to outbrake the Ducatis so consistently off the banking at Daytona. And Renfrow had even better binders for his championship chase.

He also had a better engine. Plumb constantly tinkered with the engine, which grew from 857cc at the beginning of the season to 897cc by the end, eventually producing almost 105 horsepower. In addition, the transmission gear ratios were revised so that third, fourth and fifth are now closer. The bike also lost 16 pounds over the season.

Renfrow, who rode the bike throughout its development, approved of the updates, and later said. “With those alterations, the bike changed direction more easily, even with the power increases. It was benign, very easy to ride. The total package kept getting better as the season went on. Plumb and Adams never stopped improving it."

After my ride on the RS, I can see how first Lewis and then Renfrow made Dale Quarterly's life so difficult in the Pro-Twins class. But more than anything else, I am regretfully reminded that back home in Europe, such machines as the Commonwealth RS simply have no place in racing. Until the FIM sees fit to bring the class to Europe, America remains the mecca for Twins racing in the world. GP-level racing Twins remain our forbidden fruit. And the RS, for now, is the sweetest of that fruit. Œ

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Columns

ColumnsUp Front

February 1990 By David Edwards -

Columns

ColumnsAt Large

February 1990 By Steven L. Thompson -

Columns

ColumnsLeanings

February 1990 By Peter Egan -

Letters

LettersLetters

February 1990 -

Roundup

RoundupForza Italia! Milan Show Highlights

February 1990 By Alan Cathcart -

Roundup

Roundup1990 Ducatis, Husqvarnas: Don't Call 'em Cagivas Anymore

February 1990