TOGETHER AGAIN FOR THE FIRST TIME

A HARLEY-DAVIDSON XR750 FOR THE STREET. NOT AUTHENTIC, NOT QUITE PRACTICAL, BUT THE ONLY WAY TO GET ONE IF YOU WANT ONE.

ALLAN GIRDLER

Several years ago a collector came to Daytona with, he said, the Triumph on which Gary Nixon won the 200 in 1967. Nixon was at the track so I walked over and asked if he’d like to see his partner in victory.

Nixon grinned his patented Nixon grin and declined, adding that by his count the latest arrival brought the total of winning 1967 Triumphs to three, each and every one authentic.

I laughed and walked away, thinking I’d learned something.

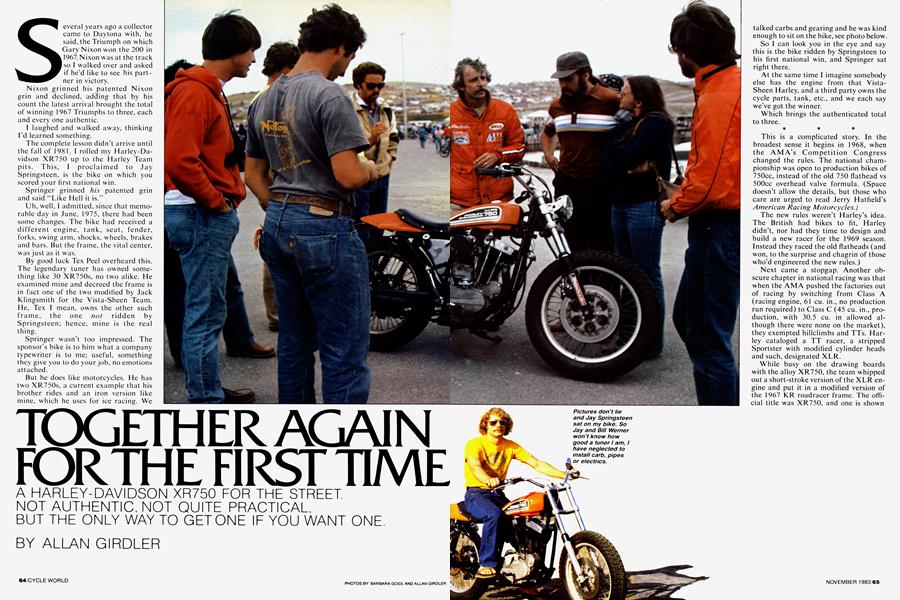

The complete lesson didn’t arrive until the fall of 1981. I rolled my Harley-Davidson XR750 up to the Harley Team pits. This, I proclaimed to Jay Springsteen, is the bike on which you scored your first national win.

Springer grinned his patented grin and said “Like Hell it is.”

Uh, well, I admitted, since that memorable day in June, 1975, there had been some changes. The bike had received a different engine, tank, seat, fender, forks, swing arm, shocks, wheels, brakes and bars. But the frame, the vital center, was just as it was.

By good luck Tex Peel overheard this. The legendary tuner has owned something like 30 XR750s, no two alike. He examined mine and decreed the frame is in fact one of the two modified by Jack Klingsmith for the Vista-Sheen Team. He, Tex I mean, owns the other such frame, the one not ridden by Springsteen; hence, mine is the real thing.

Springer wasn't too impressed. The sponsor’s bike is to him what a company typewriter is to me; useful, something they give you to do your job, no emotions attached.

But he does like motorcycles. He has two XR750s, a current example that his brother rides and an iron version like mine, which he uses for ice racing. We talked carbs and gearing and he was kind enough to sit on the bike, see photo below.

WplI~~'. So I can look you in the eye and say this is the bike ridden by Springsteen to his first national win, and Springer sat right there.

At the same time I imagine somebody else has the engine from that Vista Sheen Harley, and a third party owns the cycle parts, tank, etc., and we each say we've got the winner.

Which brings the authenticated total to three.

This is a complicated story. In the broadest sense it begins in 1968, when the AMA's Competition Congress changed the rules. The national cham pionship was open to production bikes of 750cc, instead of the old 750 fiathead vs 500cc overhead valve formula. (Space doesn't allow the details, but those who care are urged to read Jerry Hatfield's American Racing Motorcycles.)

The new rules weren't Harley's idea. The British had bikes to fit, Harley didn't, nor had they time to design and build a new racer for the 1969 season. Instead they raced the old flatheads (and won, to the surprise and chagrin of those who'd engineered the new rules.)

Next came a stopgap. Another ob scure chapter in national racing was that when the AMA pushed the factories out of racing by switching from Class A (racing engine, 61 cu. in., no production run required) to Class C (45 cu. in., pro duction, with 30.5 cu. in allowed al though there were none on the market), they exempted hillclimbs and TTs. Har ley cataloged a TT racer, a stripped Sportster with modified cylinder heads and such, designated XLR.

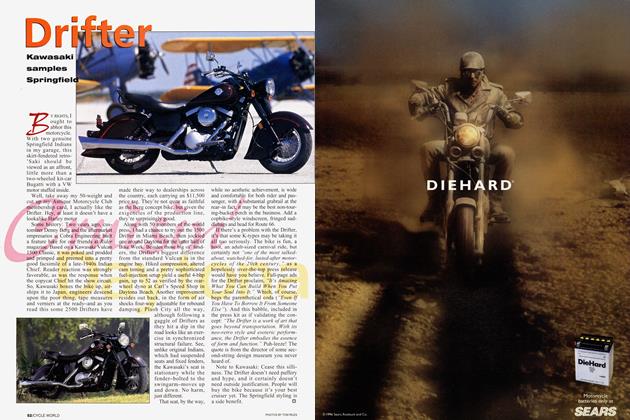

While busy on the drawing boards with the alloy XR750, the team whipped out a short-stroke version of the XLR en gine and put it in a modified version of the 1967 KR roadracer frame. The offi cial title was XR750, and one is shown press release appears at the bottom of this page, next to a newer photo of my bike: What I have done is replicate, as closely as possible, that 1970 racer.

Many of that first XR’s features were useful to me, as will be detailed, but as a racing machine it wasn’t very good.

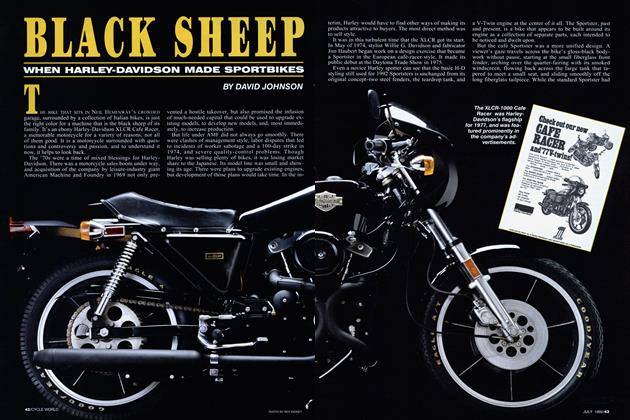

Okay, it was awful. The iron XR was slower than the flathead KR, while it generated more heat than power. The factory built the required 200 examples, then went out and got smoked. The best team rider was 6th in national standings in 1970, the highlight of 1971 was one road race win. None too soon it was 1972, the alloy XR750 appeared and has been winning ever since.

Enough background. The personal story began back with the first XR750. I fell in love the first time I saw an XR, never mind if it was fast. The perfect motorcycle, by my standards. I wished I could have one except that I always figured they weren’t for sale in stores, as they say. You’d have to be on a list, or have influential friends or something like that.

Then one day I noticed an ad, in Buzz Walneck’s Classic-Fied newspaper. It was for an XR frame and cycle parts, minus engine.

Now. Contemporary social criticism heaps abuse on the industrial practice of not obsoleting everything twice each year. Harley is scorned for not making three new engines every model year, unlike some brands I could mention.

Obsolescence may be good for the new bike buyer. But in my case I knew that the Sportster was derived from the K model, the XLR was based on the Sportster, the first XR750 was a destroked XLR, the alloy XR was built from the iron XR; they are all related. And lots of parts from one will fit the others.

Hmm. If I had that frame and suspension I could get an older Sportster engine and title and I could have me one nifty bike. Except that the price was more money than I had at the time.

I mentioned this to Walneck and he said shucks, didn’t I know asking prices are just that?

Oh. In that case, next time you see part of an XR for sale, let me know.

So it happened that late in 1980 Walneck called. He knew where to get an XR frame. Not just a frame, but the *ex-Vista-Sheen frame, as ridden by etc. I’ll take it, I said, before he even named a price.

Further, Walneck had a line on a genuine iron XR engine. Not complete, more like the cases and barrels, but to hear him tell it all I’d have to do was bolt on various little items like ignition and carb and I’d be ready to go.

Not quite, but meanwhile another look at how racing motorcycles change and multiply.

Also on this page is a shot of Springsteen, winning Louisville in June, 1975. Even to the layman, this bike is clearly different from the iron version. Peel says it’s a 1972 frame, which Klingsmith modified by re-angling the steering head, extending the backbone and lowering the engine cradle by splicing sections into the front and rear downtubes. What happened between 1975 and 1980 I don’t know, except that when Walneck got it, the frame had a Sportster engine, still another set of cycle parts and a different version of the street equipment I later installed.

At this point I found myself stuck on a tarbaby made of my own enthusiasm. The Sportster disguised as an XR750 was becoming a real XR, an historic XR. I made a down payment and Walneck was kind enough to put the parts on layaway while I saved the rest. I figured heck, do it right, and I bought the frame, what engine there was and all the parts he’d throw in, the object being an ostensible iron XR750, as introduced in 1970.

Plus road gear. I’ll never pass as a purist. Can’t stand the thought of not being able to ride my bikes when and where I please, so they must have license plates.

By a stroke of good luck, the engine had been owned and raced by Bill Milburn, an enthusiast who restores race bikes (even) older than mine. Along with the engine I got his parts book, log book, tuning and gearing data and things like a rear wheel Gary Scott sold to Milburn after he, Scott that is, quit the Harley

team.

* * *

Ready now for the third level, An XR750 For The Street.

We begin with the industrial philosophy mentioned early, the one that’s careful not to make everything obsolete. The iron 750 bolts right into the frame made for an alloy 750. Heads from a 900 Sportster bolt to the 750 barrels. Because the racing 750 was based on the street 900, the kick start from the 900 fits in the 750 cases. Not only that, but swapping parts in the timing case lets a Sportster generator go where the XR magneto used to be, and a Sportster mag where the XR tach drive was. Thus, the major road equipment was easy.

Except that no two Harleys are alike and it took several tries to get the right valves and springs and rockers for the heads. The first XR seat didn’t fit the XR frame, the stock plate to put the XR tank on the XR frame didn’t work because everything had been moved around, etc.

Then came the secondhand pieces. The oil tank leaked, the gas tank leaked, the magneto didn’t spark ... I could hardly believe it when the used generator actually generated. I went through three clutch cables, five throttle cables, two seats, two complete front ends, two front brakes. The first carb was broken where it didn’t show: suffice it to say there are sometimes good reasons for the people selling parts to have them up for sale.

And because any race bike is modified within minutes of delivery from the factory, there were problems I plain wasn’t able to handle.

Professional help was the answer. Another bonus. Just as the factory will sell a racing bike to anybody with the money, so will tuners and builders, even famous ones, work for those who can pay their bills. All I had to do was look in the back of Cycle News, make the phone calls and come up with the money.

Steve Storz, who builds and tunes for the west coast Harley privateers, and Don Vesco, world’s fastest biker, did every piece of good and skilled work you see here.

Storz machined the axles and spacers to install Grimeca brakes, as seen on all the real Harleys, mounted pegs so they’d fit me, and the brakes and gearshift.

Vesco fabricated a head stay between the heads and frame backbone, brackets for the stoplight switch, reworked the struts for the exhaust pipes, trimmed the taillight so it tucked inside the fender and a host of other items.

The pros are worth their (high) price.

Some words about that. I took great offense when a visitor said how neat the XR was, and how useful that I could declare it a “Project.” I use quote marks here because on the shabby fringes of journalism a project is where somebody with authority shakes down suppliers and puts the stuff on his personal equipment. Then it runs in the magazine, the publicity paying for the free parts.

We, meaning Cycle World and CBS, don’t do that.

Further, the XR750 is far too important for such tacky behavior. This is my bike, my very own machine and I would not cheapen it by misusing the company.

How smug that sounds. Okay, being fair, I have taken advantage of company time and money by getting free advice. Tex Peel, Jay Springsteen, Bill Werner, Brent Thompson and Jack Malone were invaluable and if it wasn’t for my press pass Ed never have got close enough to ask.

The rest of the work was done on the basis of expediency. The light switch and battery box are Honda, the kick stand is Yamaha, the brake switch and horn are Kawasaki. I bought a Barnes clutch, Strociek magneto mounting plate, reusable (I needed that feature) clutch gasket from Hawk Performance, a Voltpak regulator and countless cables from Terrycable.

For the record, wheelbase is 56 in. Test weight, so to speak, is 365 lb. The factory never listed or claimed power for the iron XR and mine is hampered by the Sportster heads with their smaller valves and lower compression ratio, and mufflers, but Ed estimate something between 50 and 60 bhp. That’s at least adequate for my needs, which brings to mind the poster about how if you save and scrimp you’ll get enough money to buy the things you were too poor to buy when you were young enough to really use them.

I have been asked what I will do with the XR when it’s finished.

Ell never know. This kind of bike is like a wooden boat, in that there’s always something that needs to be done and when you do it, there’s something else.

Time is as relative as money. In dollars the XR has cost at least as much as an XLX or Interceptor. Em not telling how much because I don't want people to know. Elapsed time is something more than two years, because I didn’t know what I was doing. A qualified mechanic, working full time, could have done this in weeks.

Even virtue is relative; by rational standards what I got for the time and money and occasional heartbreak is a motorcycle that makes noise, rides rough, seats one and probably isn’t as fast as it looks.

But that’s okay. I wanted an XR750 and I have one. Building it myself only makes it better. Bä

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Departments

DepartmentsCycle World Up Front

November 1983 By Allan Girdler -

Cycle World Letters

Cycle World LettersCycle World Letters

November 1983 -

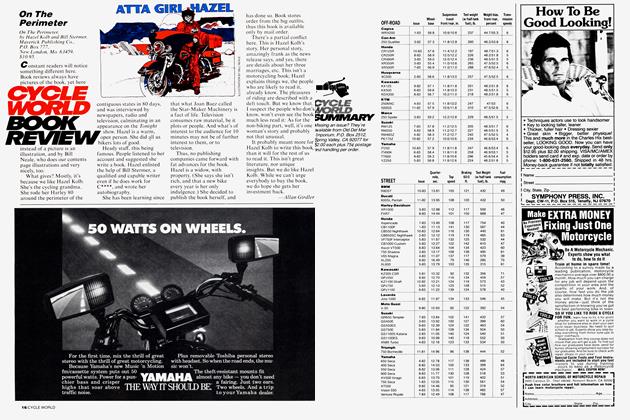

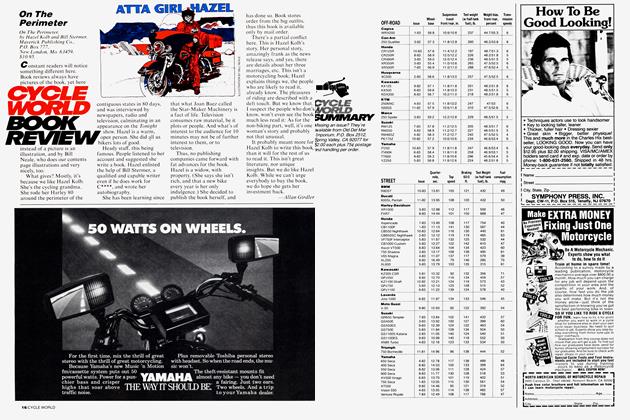

Departments

DepartmentsCycle World Book Review

November 1983 By Allan Girdler -

Departments

DepartmentsCycle World Summary

November 1983 -

Departments

DepartmentsCycle World Roundup

November 1983 -

Departments

DepartmentsCycle World Roundup

November 1983