BLACK SHEEP

WHEN HARLEY-DAVIDSON MADE SPORTBIKES

DAVID JOHNSON

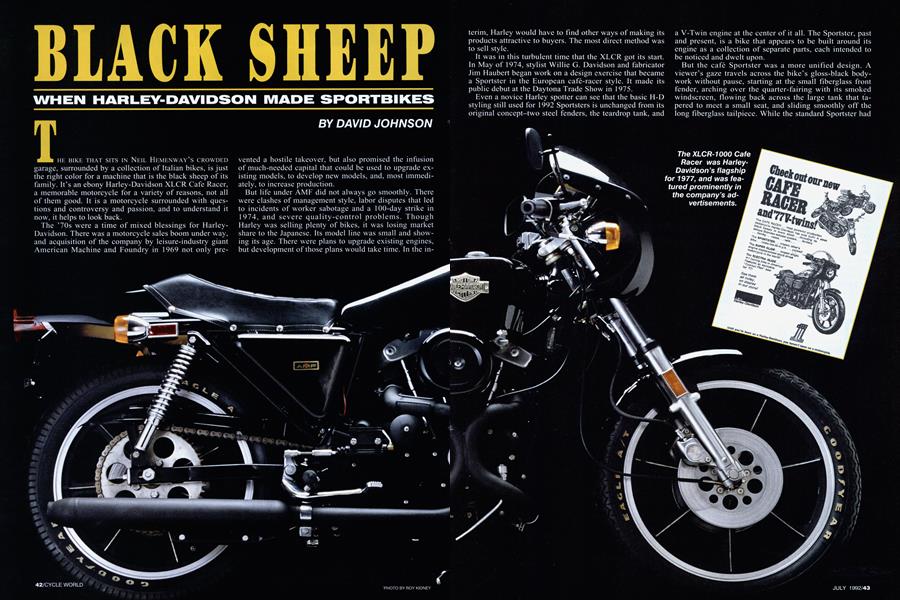

THE BIKE THAT SITS IN NEIL HEMENWAY'S CROWDED garage, surrounded by a collection of Italian bikes, is Just the right color for a machine that is the black sheep of its family. It's an ebony Harley-Davidson XLCR Cafe Racer, a memorable motorcycle for a variety of reasons, not all of them good. It is a motorcycle surrounded with questions and controversy and passion, and to understand it now, it helps to look back.

The `70s were a time of mixed blessings for Harley Davidson. There was a motorcycle sales boom under way. and acquisition of the company by leisure-industry giant American Machine and Foundry in 1969 not only pre vented a hostile takeover, but also promised the infusion of much-needed capital that could be used to upgrade cx isting models, to develop new models. and, most immedi ately, to increase production.

But life under AMF did not always go smoothly. There were clashes of management style, labor disputes that led to incidents of worker sabotage and a 100-day strike in 1974, and severe quality-control problems. Though Harley was selling plenty of bikes, it was losing market share to the Japanese. Its model line was small and show ing its age. There were plans to upgrade existing engines, but development of those plans would take time. In the interini, Harley would have to find other ways of making its products attractive to buyers. The most direct method was to sell style.

It was in this turbulent time that the XLCR got its start. in May of 1974, stylist Willie G. Davidson and fabricator Jim Haubert began work on a design exercise that became a Sportster in the European café-racer style. It made its public debut at the Daytona Trade Show in I 975.

Even a iiovice Harley spotter can see that the basic l-l-D styling still used for 1992 Sportsters is unchanged from its original concept-two steel fenders, the teardrop tank, and a V-Twin engine at the center of it all. The Sportster, past and present, is a bike that appears to be built around its engine as a collection of separate parts, each intended to be noticed and dwelt upon.

But the café Sportster was a more unified design. A viewer's gaze travels across the bike's gloss-black body work without pause, starting at the small fiberglass front fender, arching over the quarter-fairing with its smoked windscreen, flowing back across the large tank that t~t~ pered to meet a small seat, and sliding smoothly off the long fiberglass tailpiece. While the standard Sportster had itsoil tank and battery hung on opposite sides of the chas sis in plain view, the Cafe Racer located its oil tank within the triangulated rear section of the frame, and the tank was cut out to accommodate a battery, hidden by a fiber glass sidecover.

The finish applied to the prototype's component parts was the final unifying touch. The cam cover and chaincase cover were finished in wrinkle black; the dual exhaust sys tem, horn, and air cleaner cover were black chrome. Even the seven-spoke Morris wheels were blacked out.

In the mid /Us it seemed as it cate-racers would 1e the next Big Thing, and the mainstream motorcycle press, with its preference for performance, was clearly try ing to encourage this trend. Motorcyclists first encoun tered the XLCR in the June, 1975, issue of Cycle, in an article by Jess Thomas titled "Sunday Morning Special." Two years after that appearance, the XLCR became a pro duction model, but a lot had happened to the motorcycle market in those two years. Most importantly, motorcycle sales had just begun a 15-year decline that left the Japanese manufacturers sitting on large inventories and producing more motorcycles than the market could ab sorb. They countered by trying to unload these machines at fire-sale prices in the U.S. Introduced in this unhealthy environment, the limited-production XLCR, which listed for $3595, did not fare well-that same year, Honda's 750F2 was priced at $2148. About 1923 XLCRs were sold in 1977, about 1201 were sold in 1978, and 9 were sold in 1979.

BUt the glut of inexpensive Japanese bikes doesn't really account for why the XLCR didn't sell. Harley's targeted XLCR buyer probably wouldn't have been interested in buying a Japanese bike in the first place. If 1975's design exercise was indeed used to test the market, it seems reasonable to speculate that sufficient interest must have been shown by Harley's target ed buyers to justify H-D's production decision.

Yet the Summer, 1977, issue of Harley's consumer pub lication, The Enthusiast, gave this account of how the XLCR came to be, expressing a theme that would be cen tral to its advertising: "When William G. Davidson de signed the Cafe Racer, he did it with one person in mind-himself. And when Willie G. builds himself a bike, he builds an ultimate, no-compromise bike. One that's all his own. And if a production committee doesn't go for it, fine. Willie G. just keeps the motorcycle for himself. But the committee liked it, so the Cafe Racer went into limited production."

In a road test of the 1977 model, Cycle World reported-but doubted-the official line. "Corporations don't succeed," Cycle World said, by letting their creative people indulge whims, unless those whims promise to "pay off in sales, prestige, profit, or all three."

Whether Harley-Davidson's account of the XLCR's genesis is credible or not, the design exercise didn't lose much in its translation to production model. Economics surely dictated some of the changes-for example, using flat-black paint on the exhaust system rather than black chrome. Other changes were practical in nature, such as using a rubber-mounting system for the gas tank.

t~or au its ertectiveness, tne DiKes styiing was part of its problem, in more ways than one. Though the XLCR introduced a chassis, exhaust system, brake components and other parts that would, in modified form, become parts of the standard Sportster in 1979, the cost of developing its unique body parts and producing them in small numbers would have been difficult to recoup in three years of limited production. Contrast this with the Low Rider, a popular Big Twin model introduced the same year as the XLCR. Because it utilized mostly exist ing parts, it was comparatively cheap to develop and pro duce-exactly the combination Harley needed in order to buy time for engineering truly new models. The Low

Rider was a chopper for the masses, and therein lies the major reason why the XLCR failed. The Cafe Racer had the right style, but at the wrong time, for the wrong people.

The XLCR taught Harley a lesson not only about the marketplace in general in the `70s but about the styling preferences of its customers in particular, for at that time Harley's customer base consisted primarily of people who were al ready in the fold. And what they clearly liked was a Harley that looked like a Harley, which the XLCR did not. What surely drove the lesson home was the 1979 Sportster, sales of which were clearly hurt by its XLCR-derived pieces.

1 he art of building saleable motorcycles is the art of compromise, and the Sportster in particular seems to sell best as a blank slate, a starting point for the buyer's own creation. The XLCR's no-compromise style worked against this basic appeal of the Sportster.

Which brings us back to Jess Thomas's first piece about the XLCR prototype. In that story, Thomas cautioned that the bike needed performance in keeping with its looks. Did it have that performance?

erformance claims made in Harley publications and advertisements were relatively few and not terribly specific. The 1000cc XLCR was called "the most powerful production cycle HarleyDavidson has ever built. Between first and second, you shift gears," we were told. "Third is more like a launch. Fourth is almost illegal even to talk about." We were also told that the XLCR was "possessed with an abil ity to compete with the best of Europe's café-racers," that it could "hustle down a twisting road while providing out standing handling at high speeds."

Quality was never mentioned in magazine advertising for the XLCR. Perhaps it was safer to let readers unaware of Harley's quality-control problems infer quality from the bike's limited-production status.

The XLCR had, in fact, become the place for Harley Davidson to make its stand on quality control, but much more than the XLCR was at stake, for this model was to serve as the sign of a new era of quality at H-D. But quality didn't come cheaply. Vaughn Beals, then AMF's deputy group vice-president in Milwaukee, quoted in Peter Reid's Well Made in America, said, "The first 100 Cafe Racers that came off the line `ready to ship' cost us over a hundred thousand dollars to fix before they could pass inspection."

Well, that was then, and this is now. Neil Hemenway's 1977 XLCR, with 1359 miles on its odometer, provides an opportunity to look at the Cafe Racer from the perspective of 1992.

Hemenway's bike is typical of the XLCRs appearing for sale at auctions and in enthusiast publications, at prices ranging from $3800 to $6500. It's unmodified, except for the absence of the AMF stickers on the sidecovers. The XLCR's styling has aged well; it looks classic today, rather than dated. From the saddle, the bike seems incredi bly long and low, in part because of the stretch to the drag-style handlebars, but the 58.5-inch wheelbase is the same as a standard 1977 Sportster, and the ground clear ance, at a claimed 8 inches, is 1 .5 inches greater. The seat is basically a block of foam held in place by a snap-on cover. It's firm, relatively flat and long enough that a rider can vary his position.

Starting the bike is simple-a couple twists of the throttle to work the 38mm Keihin's accelerator pump, ignition on, press the starter button. The engine is remarkably quiet for a cast-iron Sportster. There's some whirring of the triplex primary chain, but mostly just a marvelous rumble from the twin mufflers. The sound of the XLCR is unique, nothing like that of the standard Sportster with staggered duals; it's something like a cross between a Sportster, a Triumph and a Ducati.

This exhaust system was partly responsible for the XLCR being the fastest stock bike Harley sold until the release of the 1983 XR1000. Dyno testing showed that the XLCR dual "Siamese" exhaust system increased both horse power and torque from 3000 to 5500 rpm. At 4000 rpm, the increase was more than 10 horsepower and 13 foot-pounds of torque. Harley-Davidson's quality-control goals also con tributed to the XLCR's performance. All Sportster engines were dyno-tested, and those with output in the top 10 per cent were pulled from the line for use in the XLCR.

Riding the XLCR in town is more work than fun. The engine is content to plonk along in high gear in town, but the clutch demands muscle, making stoplight-to-stoplight riding tiring. Sitting long at a stoplight causes a burning sensation on the inner left thigh from the hot oil tank. Gear changes demand a forceful foot but are smooth, with the exception of the shift to fourth, which always comes with a small crunch. Handling at parking-lot speeds is a bit heavy because of the low, narrow handlebar, which also places an uncomfortable amount of weight on the wrists at city speeds.

But the XLCR wasn't really intended to prowl the territory of cruisers. The fun begins when accelerat I ing the XLCR through its four gears. First and sec ond seem to exist mostly as a way to get to third, which is a real boomer. There's a big gap between third and fourth. Fourth might be illegal, as the ad copy claimed, but not on the day I rode the bike, since Hemenway had a buyer for it. The XLCR is no rocket, but in the compa ny of its brother Harleys, it's still fast. Cycle World took its 1977 test bike through the quarter-mile in 13.08 seconds at 99.66 mph; the 1200cc Evolution Sportster the magazine tested in 1991 turned in a time of 13.00 at 99.55 mph. With or without those numbers, the rising rumble from the Cafe Racer's pipes and the feeling of force working against mass give an enjoyable sensation of speed.

That enjoyment, however, does not necessarily extend to the bike's chassis, a development of that used for the standard Sportster. There's plenty of cornering clearance, but ride and handling are shortchanged mostly by the bike's suspension. Though the fork has 7 inches of travel, stiff springs and seal stiction make small bumps feel big. Rear springing, too, is stiff, but it needs to be, since there's just 2.2 inches of rear-wheel travel. To describe the ride as taut would be too generous.

Hemenway characterizes the XLCR as a great "straight ahead" bike-which it should be, with its long wheelbase, 19-inch front wheel, 29.75 degrees of rake and 4.53 inches of trail-but he calls its cornering behavior unpredictable. In smooth sweepers at legal speeds, it's steady and gen uinely fun, just the thing for a sporting gentleman on a sunny Sunday. But pavement irregularities in a corner upset the suspension, which in turn upsets the rider.

Braking is startlingly poor for a bike with three discs. Lever effort is high, and though it's easy to blame the. hard-compound pads fitted by H-D to ensure long pad life, some riders who have tried softer pads were still disap pointed. In a 1977 road test, the XLCR took 201 feet to stop from 60 mph; the 1991 1200 Sportster Cycle World tested stopped from the same speed in 127 feet. A lot of bad things can happen in 74 feet.

The motorcycle market may have had no place for the XLCR in 1977 and 1978, but today, the XLCR's unique styling and its status as the black sheep of the Harley fam ily make it a motorcycle worth owning and preserving. It is interesting as an American expression of a European concept, and as a Harley without the usual custom/cruiser connotations.

As a variation on the Sportster experience, the XLCR is a motorcycle worth riding. What's surprising is how fa miliar that experience is. The modern Sportster has smoothed, but not eliminated, the rough edges that are so apparent on the XLCR. This smoothing makes it natural to wonder whether a modern XLCR would be not only more enjoyable, but more saleable, as well.

The same thought may have crossed Willie G. David son's mind. The XLCR is one of his personal favorite de signs. He still has his 1977 XLCR, the first to roll off the assembly line, and he gave each of his sons an XLCR as a high school graduation present. In Well Made in America, he is quoted as saying, "Someday, I want to do another design that is strictly at the performance end of our mar ket. The timing wasn't right for the Cafe Racer, but I think there's a niche out there for something in between a cruis er and a performance bike."

A modern sportbike based on the Sportster would be a long and risky reach for Harley-Davidson. But, who knows. With Willie G. drawing the lines, the 1990s just might hold a place for a kinder, gentler version of the black-sheep XLCR.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Up Front

Up FrontAndy Rooney Rides

July 1992 By David Edwards -

Leanings

LeaningsThe Whites of Their Eyes

July 1992 By Peter Egan -

TDC

TDCA Matter of A Pinion

July 1992 By Kevin Cameron -

Letters

LettersLetters

July 1992 -

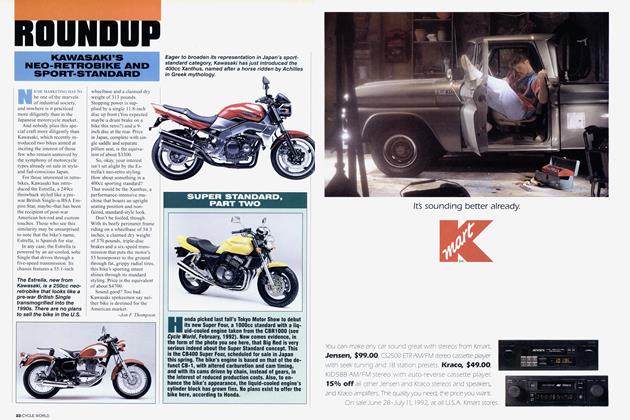

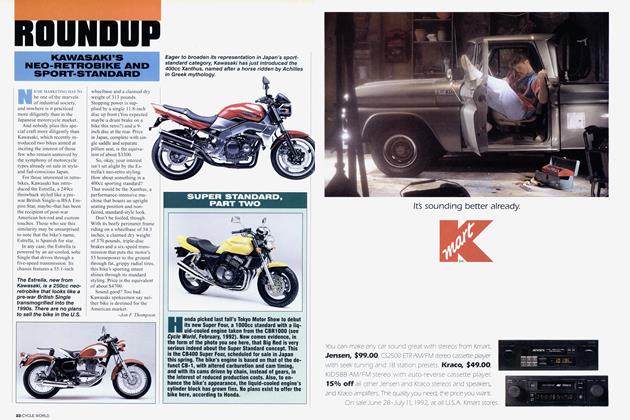

Roundup

RoundupKawasaki's Neo-Retrobike And Sport-Standard

July 1992 By Jon F. Thompson -

Roundup

RoundupSuper Standard, Part Two

July 1992