THE ELECTRIC MYTH

Cutting the cord, and other steps toward the future of efficient motorcycling

Because fuel prices and transportation are hot issues for Americans, political rhetoric threatens to wash the facts right out of the discussion. This has led to many people becoming impatient for the clean, sensible hydrogen economy. There’s hydrogen in water and the oceans are full of water, so let’s do it! But it takes just as much power to set that hydrogen free from water as is released when the freed hydrogen burns. This means the power to free the hydrogen might as well be used to move the vehicle in the first place. Hydrogen is not an energy source, it is an energy carrier.

Similar misconceptions surround electric vehicles. When originally proposed, people assumed they’d just plug their electric cars into the wall and for a few cents they’d charge up for tomorrow’s commute. Then California had its brown-out energy crisis, suggesting that powering that state’s millions of cars through the electricity grid was a faint hope even if-as was never proven-the cars could be made practical and affordable.

So how much power do we need and how do we get it? Small cars at highway speed use a steady 20-25 horsepower, motorcycles just 10-15. At a four-stroke engine’s fuel requirement of 0.50 pounds of fuel per horsepower-hour, at 65 mph that is 32-40 mpg for a car and more than 60 mpg on some of the more fuel efficient motorcycles. If we switch to diesel power, at more like 0.38-lb/hp-hr, that becomes 42-53 mpg on four wheels, 80-plus on two, (or even more, as diesel fuel is denser than gasoline). In terms of conversion of fuel energy to power, the gasoline vehicle may achieve 25 percent efficiency, a diesel perhaps 33 percent.

Now let’s do electric power. Efficiencies multiply, so we must consider production, transmission, transformers, storage and use. Totaling all this up gives us 22 percent efficiency-no better than gasolineor diesel-powered vehicles.

When public officials confront such figures, they reply correctly, “Yes, but efficiency isn’t the point. The point is to remove vehicle emissions from urban areas.”

Point taken. But we must also accept that electric vehicles do not save energy. They just move the pollution out of town, to whatever neighborhood hosts our new electric powerplants.

Vehicle efficiency can be improved. It is inefficient, for example, to take that 20-25 hp from a big engine, running at low part-throttle. The reason is that lubricating oil films are most efficient when they are loaded to just short of failure. But if we make our engines very small to achieve this, our cars and motorcycles accelerate like cold syrup-no fun. One way to restore the lost acceleration is to turbocharge, which is what the Europeans do to make their new diesel autos both economical and fun to drive.

Another way is to somehow store energy on-board, and use that energy to boost performance during acceleration. A big rubber band is one way. In practical terms that’s what the new hybrids are. A small combustion engine, operating at fairly heavy throttle, drives the vehicle efficiently at highway speed. Meanwhile some of its energy is used to charge a battery, storing energy. Then, when you need to pass or zoom up an on-ramp, opening the throttle also calls on this stored energy, making acceleration adequate if not actually thrilling.

There’s more. When braking in stop-and-go traffic, a hybrid can slow itself by operating its electric motor as a generator, putting some of the “braking energy” back into on-board storage. When the vehicle accelerates again as the light turns green, part of the energy required is “free” in the sense that it was not wasted as brake heat but was stored and used again.

Stopped in traffic, the hybrid’s combustion engine shuts down so no fuel is used in idling. The stored energy in the battery is plenty for many cycles of gridlock inchings-forward. When the battery needs a charge, the main engine cuts in and does the job, operating at its most efficient rpm and throttle.

Hybrids are expensive because they have two power systemsthe combustion engine and the motor/generator/battery system. Mass production can reduce the price somewhat, but two powerplants will always be more expensive than one. Figure the cost of the fuel saved by the hybrid’s somewhat greater fuel economy and see if it covers the added first cost of the vehicle.

A hybrid motorcycle? Right now, roughly half of a motorcycle’s weight is its engine, and room aboard is hard to find. Cars are full of sofas, doors, and sound systems, and there is plenty of extra room. How can a motorcycle accommodate a second power system? Aha, we’ll just adopt a more upholstered and auto-like styling and fill its streamlined plumpness with batteries, rectifiers, controllers and the necessary motor-generator, as Yamaha did with the “Gen-Ryu” that debuted at last fall’s Tokyo Motor Show. Just get your mind right about the 1950s Schwinn look. It’ll be fun. -Kevin Cameron

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Up Front

Up FrontWorld's Fastest Indian

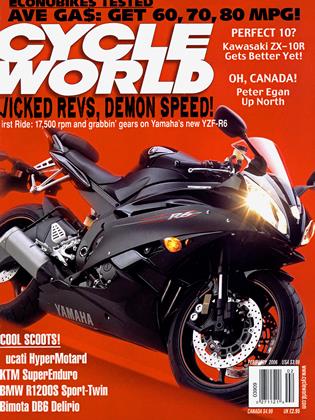

February 2006 By David Edwards -

Leanings

LeaningsBeemer Report Card, Summer Semester

February 2006 By Peter Egan -

TDC

TDCUntying Knots

February 2006 By Kevin Cameron -

Departments

DepartmentsHotshots

February 2006 -

Roundup

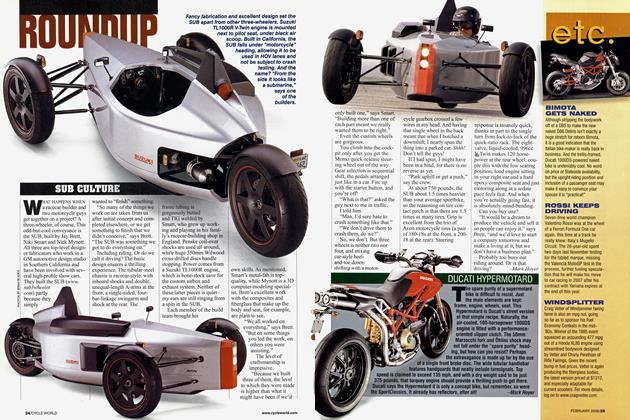

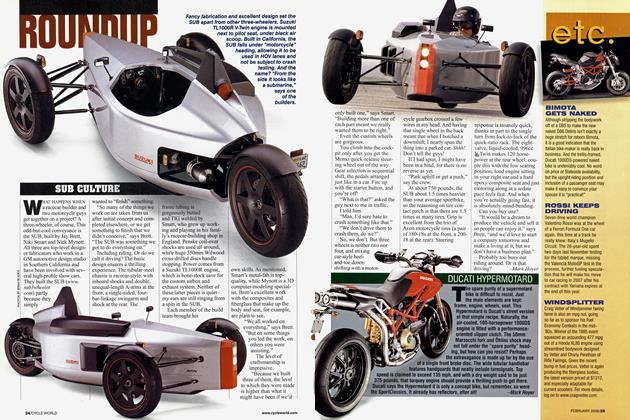

RoundupSub Culture

February 2006 By Mark Hoyer -

Roundup

RoundupDucati Hypermotard

February 2006 By Mark Hoyer