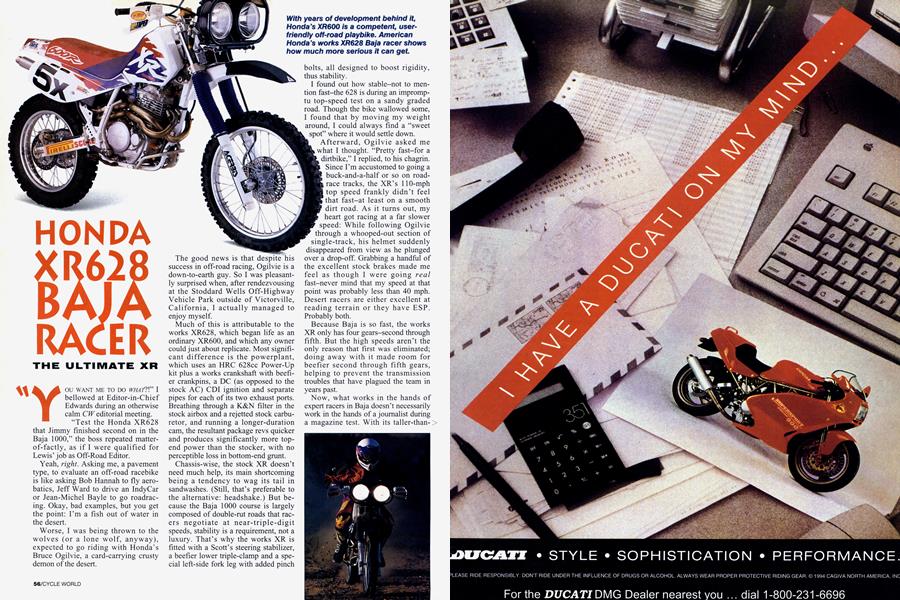

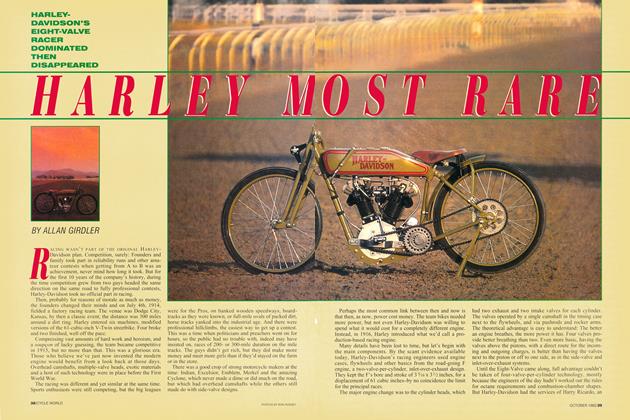

HONDA XR628 BAJA RACER

THE ULTIMATE XR

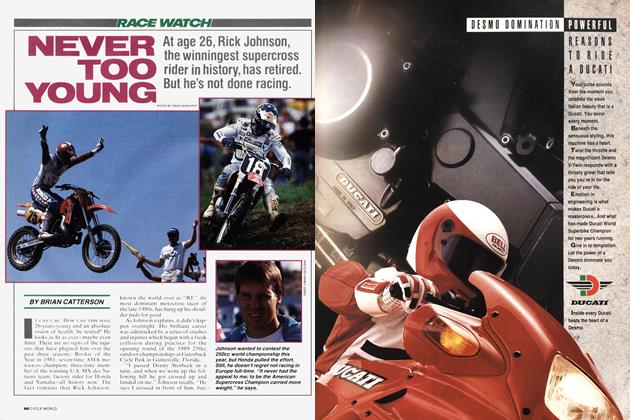

YOU WANT ME TO DO WHAT?!" I bellowed at Editor-in-Chief Edwards during an otherwise calm CW editorial meeting. “Test the Honda XR628 that Jimmy finished second on in the Baja 1000,” the boss repeated matterof-factly, as if I were qualified for Lewis’ job as Off-Road Editor.

Yeah, right. Asking me, a pavement type, to evaluate an off-road racebike is like asking Bob Hannah to fly aerobatics, Jeff Ward to drive an IndyCar or Jean-Michel Bayle to go roadracing. Okay, bad examples, but you get the point: I’m a fish out of water in the desert.

Worse, I was being thrown to the wolves (or a lone wolf, anyway), expected to go riding with Honda’s Bruce Ogilvie, a card-carrying crusty demon of the desert.

The good news is that despite success in off-road racing, Ogilvie is a down-to-earth guy. So I was pleasantly surprised when, after rendezvousing at the Stoddard Wells Off-Highway Vehicle Park outside of Victorville, California, I actually managed to enjoy myself.

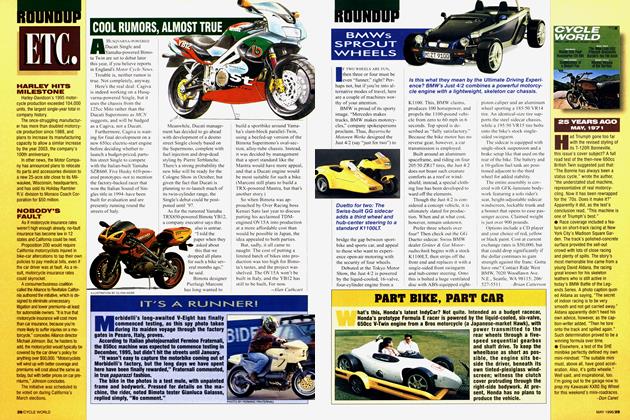

Much of this is attributable to the works XR628, which began life as an ordinary XR600, and which any owner could just about replicate. Most significant difference is the powerplant, which uses an HRC 628cc Power-Up kit plus a works crankshaft with beefier crankpins, a DC (as opposed to the stock AC) CDI ignition and separate pipes for each of its two exhaust ports. Breathing through a K&N filter in the stock airbox and a rejetted stock carburetor, and running a longer-duration cam, the resultant package revs quicker and produces significantly more topend power than the stocker, with no perceptible loss in bottom-end grunt.

Chassis-wise, the stock XR doesn’t need much help, its main shortcoming being a tendency to wag its tail in sandwashes. (Still, that’s preferable to the alternative: headshake.) But because the Baja 1000 course is largely composed of double-rut roads that racers negotiate at near-triple-digit speeds, stability is a requirement, not a luxury. That’s why the works XR is fitted with a Scott’s steering stabilizer, a beefier lower triple-clamp and a special left-side fork leg with added pinch bolts, all designed to boost rigidity, thus stability.

I found out how stable-not to mention fast-the 628 is during an impromptu top-speed test on a sandy graded road. Though the bike wallowed some,

I found that by moving my weight around, I could always find a “sweet

spot” where it would settle down. Afterward, Ogilvie asked me what I thought. “Pretty fast-for a dirtbike,” I replied, to his chagrin. Since I’m accustomed to going a buck-and-a-half or so on roadrace tracks, the XR’s 110-mph top speed frankly didn’t feel that fast-at least on a smooth dirt road. As it turns out, my heart got racing at a far slower speed: While following Ogilvie through a whooped-out section of single-track, his helmet suddenly disappeared from view as he plunged over a drop-off. Grabbing a handful of the excellent stock brakes made me feel as though I were going real fast-never mind that my speed at that point was probably less than 40 mph. Desert racers are either excellent at reading terrain or they have ESP. Probably both.

Because Baja is so fast, the works XR only has four gears-second through fifth. But the high speeds aren’t the only reason that first was eliminated; doing away with it made room for beefier second through fifth gears, helping to prevent the transmission troubles that have plagued the team in years past.

Now, what works in the hands of expert racers in Baja doesn’t necessarily work in the hands of a journalist during a magazine test. With its taller-than-> stock primary and final drive ratios, letting out the clutch in first (or is it second?) gear requires a healthy twist of the right wrist and some fancy work with your clutch hand to keep from stalling. Yet once underway, you can lug the 628 down to near-walking speeds without a problem. Most of the time. I did manage to stall the XR on occasion, most notably while doing repeated U-turns during a photo shoot. Yet the big Single proved fairly easy to start, provided you remembered to find TDC on the compression stroke. A compression release is fitted, but this is most useful for clearing out the cylinder if you flood it (don’t ask how I know). I felt bad about stalling it until Ogilvie informed me that Lewis also killed the motor when he climbed aboard for his first stint in Baja. Heh, heh.

Like most Thumpers, the XR628 will wheelie, but thanks to the tall gearing, you’ve got to be going about 50 mph to do so. Tugging on the bars as you complete the first-to-second shift usually results in the front end jumping skyward.

Speaking of jumping skyward, doing so in a literal sense results in a solid landing, due to the XR’s heavy (by motocross standards) weight. Yet the suspension, consisting of a revalved stock shock and a stock fork fitted with late-’80s CR250 damper rods, is plush and progressive, soaking up small chop and big whoops with equal aplomb.

I learned to appreciate the suspension when, after fitting the dual Cibie headlights, I ventured out into the night to get a taste of what my coworker went through South of the Border. Lewis took over from teammate Johnny Campbell shortly after nightfall, and rode most of the remaining 480 miles to the finish in the dark.

What’s neat about riding at night is that everything casts shadows, so rocks and whoops rarely take you by surprise. The works XR’s frame-mounted lights work well because they always point toward where you’re going; handlebar-mounted units point the wrong way when you’re crossed up, broadsliding through a turn.

Fast guys do that a lot in Baja.

Unfortunately, after hitting a few hundred small whoops casting big shadows, you begin to think that they’re all small, so when you finally do encounter a big one, it’s a shocking discovery. How do you tell the difference? It’s that ESP thing again.

Returning from my brief night ride, Ogilvie said something that put Lewis’ Baja performance in perspective.

“Only 476 miles to go,” he joked. Sobering thought.

Besides the challenging terrain and darkness, Baja racers have to deal with other hazards, such as animals, nonrace traffic and the increasingly common “booby traps” set up by bored locals. These can be anything from dirt jumps to telephone poles laid across the trail designed to separate man from machine. Sickening.

Asked to compare the Baja 1000 with the Granada-to-Dakar Rally he recently competed in, Lewis replied, “Baja is more of a sprint race. You basically race from pit stop to pit stop.” A word about those pit stops: There are 21 of them, spaced about 50 miles apart, each taking just 10-15 seconds to complete. What this means is the racers have a very long way to go with little rest.

Off-road racing is one of the toughest disciplines in motorcycling, and Honda’s works XR628 is designed to make its rider’s job as easy as possible. Which, if you ask me, could never be easy enough.

Brian Catterson

View Full Issue

View Full Issue