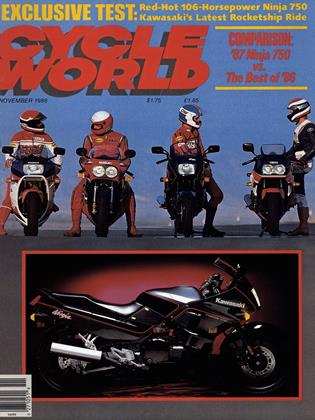

NINJA TECH

KAWASAKI SHRINKS AND REFINES THE INLINE FOUR

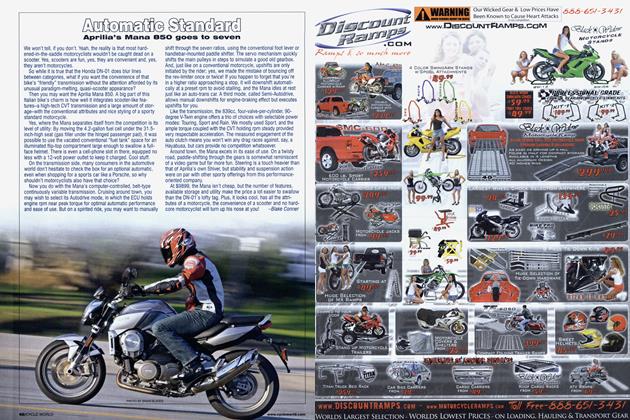

KAWASAKI ENGINEER MATSUNAGA IS PROUD: "This new engine is the most compact and the most powerful in its class. It makes 106 horsepower without being big or heavy. Without carbs, it weighs 147 pounds. As for size, the Suzuki GSX-R750 engine is wider, the Yamaha FZ is taller and longer, and the Honda VFR is longer. Our new 750 engine is actually shorter and narrower than even a Ninja 600 motor."

Two years ago, in September of 1984, when charged with designing the Ninja 750 engine, Matsunaga may have been less sure of himself. He doesn’t say so, but the impetus then fora new motorcycle was obvious. Yamaha and Suzuki were just announcing their FZ and GSX-R 750s, forever changing the rules for power and bulk in the 750 class. Neither was just another motorcycle; they were their respective company’s best efforts, corporate flagships flying the standards of high technology and high performance. Any new Kawasaki would have to match, or better, those standards.

But for Matsunaga and Kawasaki there were no doubts about how to compete: An inline-Four was called for, the best inline-Four that Kawasaki could build. Wrapped around it would be a smaller, lighter motorcycle than previous 750 Kawasakis had been. And while this newest Ninja would be sporting, it would not be a racer replica; Suzuki could have that market. Instead, Kawasaki intended to match racerreplica performance without forcing 750 Ninja riders to forego all comfort.

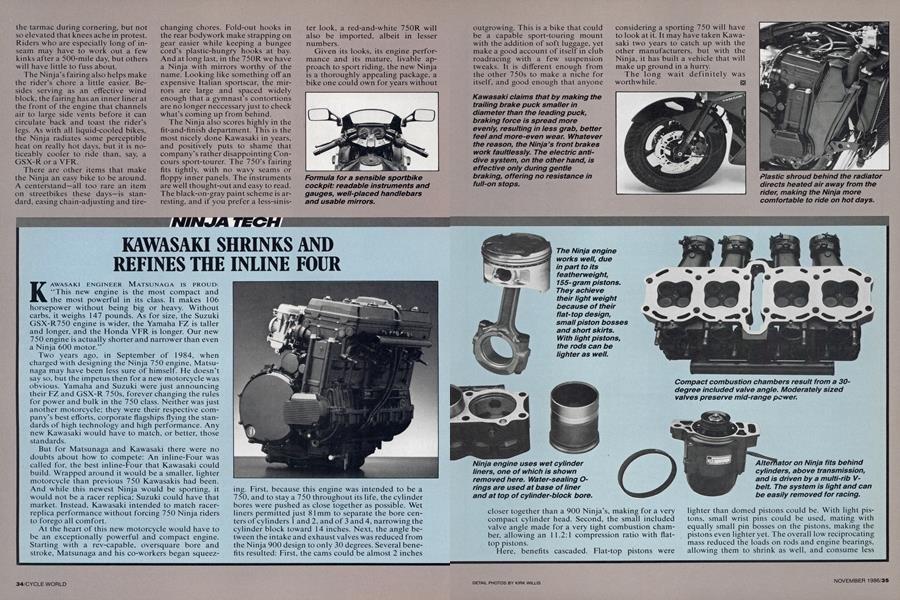

At the heart of this new motorcycle would have to be an exceptionally powerful and compact engine. Starting with a rev-capable, oversquare bore and stroke, Matsunaga and his co-workers began squeezing. First, because this engine was intended to be a 750, and to stay a 750 throughout its life, the cylinder bores were pushed as close together as possible. Wet liners permitted just 81mm to separate the bore centers of cylinders 1 and 2, and of 3 and 4, narrowing the cylinder block toward 14 inches. Next, the angle between the intake and exhaust valves was reduced from the Ninja 900 design to only 30 degrees. Several benefits resulted: First, the cams could be almost 2 inches closer together than a 900 Ninja’s, making for a very compact cylinder head. Second, the small included valve angle made for a very tight combustion chamber, allowing an 11.2:1 compression ratio with flattop pistons.

Here, benefits cascaded. Flat-top pistons were

lighter than domed pistons could be. With light pistons, small wrist pins could be used, mating with equally small pin bosses on the pistons, making the pistons even lighter yet. The overall low reciprocating mass reduced the loads on rods and engine bearings, allowing them to shrink as well, and consume less

power in friction. Also, vibration was reduced, so the counterbalancer that Kawasaki had deemed necessary on the 900 Ninja engine was eliminated. Matsunaga notes that this last move didn’t reduce motorcycle weight; rubber front engine mounts and extra frame structure added the pounds to the chassis that the engine had lost. But the engine was smaller and simpler without the balancer.

Packaging of the gearbox and accessories finished the weight-and-space-saving theme. The distance between the gearbox input and output shafts was reduced compared to the 900 Ninja, saving weight not just with the smaller gears, but also with the shorter engine cases required. But it is the space utilization behind the cylinders and under the carbs that most pleases Matsunaga; a jackshaft there is driven by a chain from the crank, and in turn drives (via another chain) the oil pump and water pump below it, and (with a belt) the alternator above it. The belt is light and damps shock loads, which eliminates the need for a separate mechanical damper. Matsunaga describes the final engine design as “very dense, like an integrated circuit.”

So the engine was successfully pressed down into a small size. But meeting the power goal required more: a valve train that could survive at the highest engine speeds. Matsunaga gave the Ninja relatively small, light valves, opened by individual rocker arms. Screw adjusters were positioned at the pivot end of the rockers, and the cam lobes placed almost directly over the valves—both features that reduce the weight the springs have to control. Again, light weight brings a cascade of benefits: Light valves and rockers can be controlled with relatively light spring pressures; light spring pressures reduce the load at the cam face, so cam lobes can be narrower, and friction less. This type of good detail design produced valves that open and close reliably even at 14,500 rpm. The rev-limiter cuts the Ninja’s ignition at 12,200 rpm, but that safety margin reveals the potential for further tuning.

Short, free-flowing intake and exhaust ports are the final part of the power-producing equation. The intake tracts do require the incoming charge to turn a corner, but not as dramatically as in previous Kawasaki engines. To boost mid-range power, the Ninja engine uses smaller valves and port sizes than do some other sporting 750s, and ties the carburetors to the airbox with rubber boots that continue the carburetor inner diameter. These effectively increase the length of the intake tract, optimizing intake ram-tuning at mid-range rpm levels.

If the Ninja 750’s engine gives some hints of déjà vu, its frame will strengthen that “I’ve-seen-it-before” feeling. Round-section steel tubing makes up the main frame, bent and welded into a structure that harks back to the Norton Featherbed. The rear subframe (supporting only the rider and bodywork) is aluminum. But traditional appearance doesn’t imply a lack of sophistication. By using large-diameter tubing (1.3-inch), Kawasaki claims to have increased frame stiffness beyond that of the 900 Ninja. And with a total weight of 29 pounds for the front and rear frame sections, this design is actually lighter than at least one competing aluminum frame.

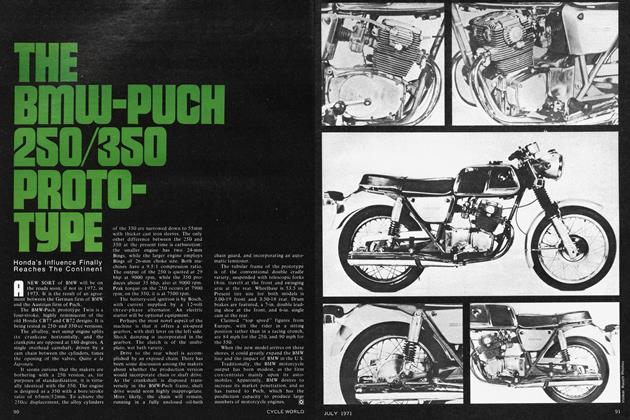

Perhaps as important as the frame is the bodywork that covers it. Continuing the tradition set by the 600 Ninja, the new fairing is very aerodynamic (Kawasaki claims a 17-percent reduction in drag with the fairing installed). Wind tunnel time was spent in more than making the 750 Ninja slicker; ducting channels engine and radiator heat away from the rider’s legs, replacing superheated air with a cooler breeze.

In the end, though, there is no single design feature, such as the FZ’s five valves per cylinder or the GSXR’s light weight, that will define the Ninja 750. Instead, this machine represents the refinement and development of conventional concepts that Kawasaki understands well. And in that refinement, engineer Matsunaga and his colleagues can find good reason for their pride. S

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Departments

DepartmentsEditorial

November 1986 By Paul Dean -

Departments

DepartmentsAt Large

November 1986 By Steven L. Thompson -

Letters

LettersLetters

November 1986 -

Roundup

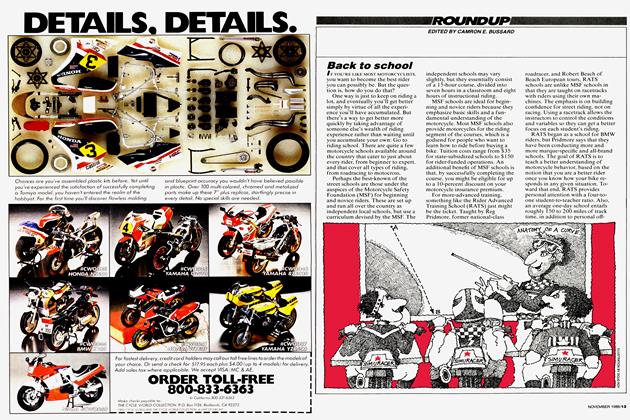

RoundupBack To School

November 1986 By Camron E. Bussard -

Roundup

RoundupLetter From Japan

November 1986 By Koichi Hirose -

Roundup

RoundupLetter From Europe

November 1986 By Alan Cathcart