AT LARGE

Single-minded (occasionally)

BY NOW, YOU'VE HEARD ALL ABOUT the new Yamaha SRX-6. You’ve read the tests, seen one of the two-per-dealer in your neighborhood, and probably absorbed the five facts necessary to fill out your own mental file card on the bike. Probably for you, as for most riders, one entry on that file card reads, “596cc kick-started four-valve Single. Of interest to antiquarians and slowpokes.”

Delete that entry and reopen the file. This bike deserves a lot more scrutiny than that, and deserves better than to be written off as just an attempt by Yamaha to salvage yet another use for its big thumper engine. You don’t have to be an antiquarian or a slowpoke to appreciate it. But you do have to engage your brain a little to see why a 105-mph, 400pound streetbike merits your attention, even if you’re an adrenaline junkie who gets his kicks dragging knees aboard something with a power-to-weight ratio that makes a Saturn booster seem pallid by comparison.

Exclusive of the qualities of the bike (about which more later), there are two reasons: the One True Motorcycle Syndrome, and the Lost in the Toy Store Phenomenon.

They’re interrelated, but The One True Motorcycle Syndrome is the easiest to define. It derives from some early experience we have as motorcycle neophytes, and it cements itself in place within the first half-decade of our involvement with bikes. It’s related to our self-image, and other such introspective and therefore socially unaddressed stuff, and it manifests itself this way: For a long, long time, we see each new bike we buy as another step up. Up in power, in speed, in style, in something. We believe that each bike has to be better—and we define “better” in ways that always are backed up by those same five facts per file card noted above, at least consciously.

In short, we see our new purchases as an escalator leading us to the One True Motorcycle. How many times have we peered at some new machine and thought, “Man, that bike is neat, but if only it had (fill in the blank).” This is the playing out of the myth of perfectability. And a myth it is, if for

no other reason than this: What’s perfect for Rider A will never be perfect for Rider B, even though we all begin with the same mass-produced equipment. Think of it as the motorcycle equivalent of Original Sin.

That’s one reason a lot of us are going to (wrongly) ignore the SRX-6. Another is the Lost in the Toy Store Phenomenon. The staggering outpouring of attractive stuff that Japan has sent us over the last 20 or so years has jaded us almost unbelievably. The motorcycle toy store is so huge that you can spend years in one department-touring bikes, say, or sportbikes, or ATVs. Almost in defense, you even get so you hardly ever venture out of that department. So as your life ticks by, you find you’ve owned and ridden a lot of the same kind of bikes. This phenomenon is especially virulent when coupled to marque-freakism, and denies you not just access to the other parts of the store, but the chance to find out what all the fuss is about when some radical new bike is unveiled.

The SRX is not radical, but it is new, and a lot of riders are obviously lost in their own toy stores or they’d be paying it a lot more attention. Not because it’s a Yamaha, not because it seems mostly built for Japanese and European riders, but because it’s about the only true road-going modern Single around right now.

So what? This is what: It’s different. So different from anything an under-30 rider is likely to have encountered that it’ll take his breath away with its simplicity, its lightness, its agility, its engine’s flexibilty, its

ability to connect its rider with the environment in an almost electrifying way. Nothing a typical American street rider of the new age has ever ridden is likely to have prepared him for what 50 miles on the SRX will show him. Perhaps used to boring discourses by old guys about their oncewonderful Norton and BSA Singles, perhaps even exposed to them at classic bike meets, he will inevitably be astounded at the nuances of a ride on an SRX-6.

Some people evidently see the difference of the SRX as a drawback— and that’s their loss. Outgrowing the One True Motorcycle Syndrome and the Toy Store Phenomenon takes some doing: but once you manage it, you realize that the one hundred years of the motorcycle have given us a wealth of ways to enjoy our passion for two-wheeled adventure. And having realized that, you also realize, almost with a jolt, that the true joy of the mature enthusiast is to taste as much as possible of the cornucopia, not to condemn its fruit.

In practical terms, anyone interested in this needs to think like the enthusiasts of Alaska, some of whom I met after I rode there on the famed Alaska Highway. They must cram as much enjoyment as possible into their short riding season, so it is not at all unusual to see a guy who the week before was aboard a six-cylinder touring rig pass by aboard a street/trail bike, grin as wide on one as it was on the other. Most of us in the Lower 48 are blessed with slightly better riding seasons, so we need not be quite so frantic about it, but the lesson is clear: You only have so much time to ride. How will you spend it?

Everyone has his or her own response. But I can’t resist spending it on such devices as the SRX, when fate offers a ride or the bank offers a loan. And every time I begrudge the expense, I remember what it’s like to try the same thing with cars. Think of it this way: For the price of indulging your curiosity about what it would be like to own just one Lamborghini, you could just about buy an example of every kind of streetbike now on the market.

Including, of course, the SRX-6.

Steven L. Thompson

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Departments

DepartmentsEditorial

November 1986 By Paul Dean -

Letters

LettersLetters

November 1986 -

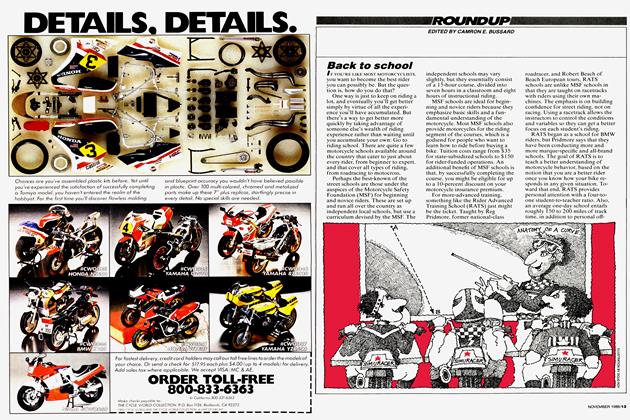

Roundup

RoundupBack To School

November 1986 By Camron E. Bussard -

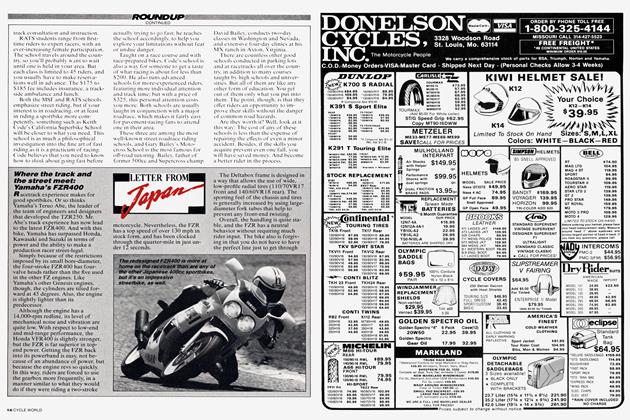

Roundup

RoundupLetter From Japan

November 1986 By Koichi Hirose -

Roundup

RoundupLetter From Europe

November 1986 By Alan Cathcart -

Features

FeaturesCactus, Cattle And the Confederate Air Force

November 1986 By Frank Conner