UP FRONT

Men of letters

David Edwards

NOVELIST CHARLES DICKENS, IN HIS Pickwick Papers, talked of “the great art o' letter-writin'.” Well. Victorian England’s got nothing on present-day North America, if the correspondence we receive at Cycle World is any indication.

Every day, the postman drops off an assortment of letters covering just about every two-wheeled subject under the sun. A few—usually scrawled with blunt crayons on scraps of paper that happened to be handy —are loosely constructed and ramble along without making much of a point, but most are expressive, insightful pieces that make a lot of sense. You let us know when we’ve printed something you like; and you fire off derogatory missives when the opposite is true.

For a while, we’ve been receiving letters that complain of the high cost of riding motorcycles, with the price tags of new bikes being singled out as especially repulsive. Now, I’m not about to argue with those of you who feel that way.

But Richard Taylor is.

Taylor is a Cycle World reader, has been since 1964. He’s also a “slightly older-than-average graduate student in economics,” who recently mailed a letter to the magazine. The letter contained the results of Taylor's research into the motorcycle industry's pricing history over the past 25 years. What he found may surprise you.

To see if the cost of motorcycling had risen as dramatically as some people think, Taylor picked three 1965 bikes—a Harley-Davidson Sportster, a 650 and a 250—and compared their prices to what similar machines cost in 1989, 25 years later. He did the same for the cost of lightweight leather jackets, piston-andring sets and hourly shop rates.

Comparing the Sportsters’ prices was easy: In 1965, a Sporty cost $1400, and in 1989, there were still several Sportsters in H-D’s lineup. Taylor picked the dual-seat XLH 883 Deluxe model costing $4665. The 650cc class was a little trickier. From 1965, Taylor picked an $1150 Triumph Bonneville, a bike no longer in production. So. for the Bonnie’s 1989 650 counterpart, a Honda Hawk GT was chosen, priced at $4198. The 250cc class had a similar predicament. This time a $645 1965 Honda 250 Hawk was put up against a $2000 1989 Yamaha Route 66. (Yes, statisticians in the audience are correct, list price on a Route 66 was $2499. The S2000 figure represents a discounted price for this not-toopopular model.)

Ah-ha, you say, the price differentials—$1400 versus $4665, $1150 versus $4198, $645 versus $2000— prove the point: Motorcycles today are too damned expensive. But you're jumping to conclusions, says Taylor; you’re not taking inflation into account.

At this point in his letter, Taylor, being a good economics student, has charts and consumer price indexes and explanations. I'll give you the condensed version. Using the 1989 “Economic Report to the President” for his numbers, Taylor notes that the average weekly salary in the U.S. in 1965 was $95. ín 1989, that figure had risen to $327. But the cost of consumer goods had risen, as well, meaning that $32 worth of 1965 goods took all of $ 120 to purchase in Ï 989.

Now. here comes the interesting part. Factoring inflation into the equation, Taylor says that 25 years ago, a total of 14.67 weeks of work were required for the average guy to buy a Harley Sportster. In 1989, 14.27 weeks’ worth of labor were needed, 2.7 percent less than in 1965. And, as Taylor points out, no value was placed on 24 years of development in handling, braking, quality control and reliability. Things were a little less rosy in the 650cc class, where our 1989 worker would have had to toil away for an additional 32 hours over his 1965 buddy to get a new bike, an effective increase of 6.6 percent. “But the Triumph Bonneville, as good as it was, is not (technologically) comparable to the Hawk 650,” notes Taylor, quite rightly. The 250cc class? Taylor’s figures show it took 6.76 1965 salary weeks to ride the Honda 250 home, against 6.12 1989 salary weeks for the Route 66, a drop of 9.5 percent.

Furthermore, Taylor found that after adjustments for inflation, a piston-and-ring set had actually declined 10 percent in price over the years, and one hour of shop time had gone down 8.5 percent. The leather jacket hasn’t fared so well in the past quarter-century, with a rise of 18 percent. Taylor doesn’t offer an explanation for this, though the increased demand for animal hides by the fashion-garment industry must have something to do with it.

And, yes, Taylor’s numbers notwithstanding, some touring bikes, some sportbikes and some Harleys are pushing well into the five-figure price range; insurance costs in some categories are higher now and getting higher; and many parts and accessories do seem to have skyrocketed ahead of inflation. But the next time you’re about to put pen to paper in protest of the high cost of new motorcycles, you may want to think about the conclusions Taylor has drawn from his motorcycle price studies.

“The prices of motorcycles are no different than anything else. Movies in 1965 were 25 cents, soda pop was a dime, beer was 30 cents, jeans were $5 and a Ford Mustang was $2300,” he writes. “The (motorcycle) industry has not priced itself out of the market. In some cases, prices have actually fallen when wages and inflation are accounted for. You don't need $ 10,000 to enjoy motorcycling. There are many bikes available for under $4500. Motorcycling is still an affordable sport.”

Honesty in reporting forces me to note another category that Taylor looked into. The cover price of a 1965 issue of Cycle World was 50 cents; in 1989, it had jumped to two bucks. Even taking inflation into account, that’s an increase of 14.3 percent.

I can already see the letters we’re going to get about that.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Columns

ColumnsAt Large

February 1990 By Steven L. Thompson -

Columns

ColumnsLeanings

February 1990 By Peter Egan -

Letters

LettersLetters

February 1990 -

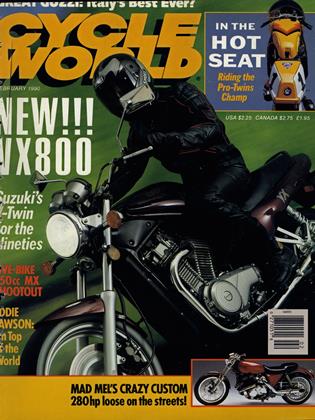

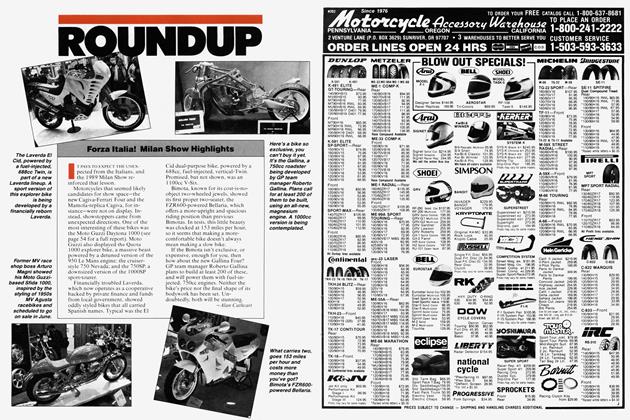

Roundup

RoundupForza Italia! Milan Show Highlights

February 1990 By Alan Cathcart -

Roundup

Roundup1990 Ducatis, Husqvarnas: Don't Call 'em Cagivas Anymore

February 1990 -

Roundup

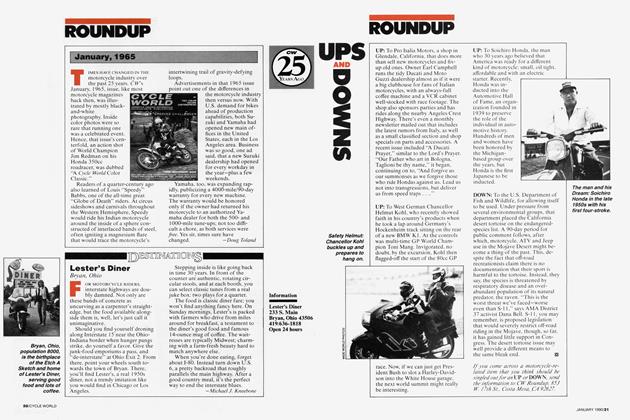

RoundupCw 25 Years Ago January, 1965

February 1990 By Doug Toland