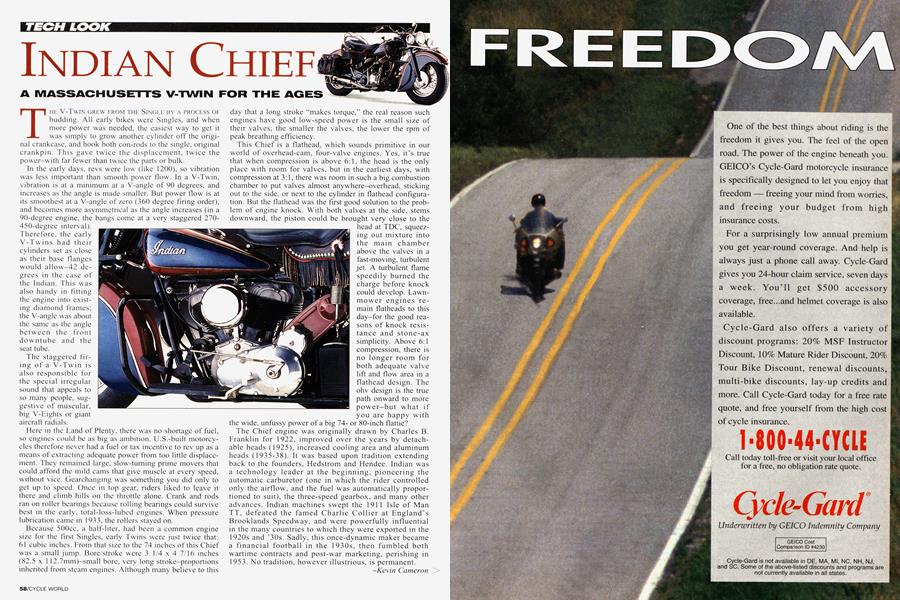

INDIAN CHIEF

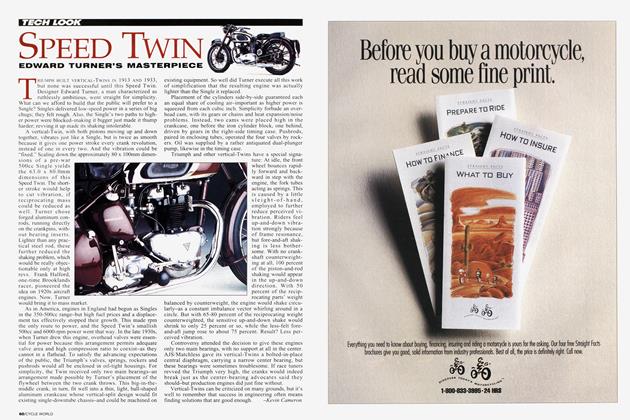

TECH LOOK

A MASSACHUSETTS V-TWIN FOR THE AGES

THE V-TWIN GREW FROM THE SINGLE BY A PROCESS OF budding. All early bikes were Singles, and when more power was needed, the easiest way to get it was simply to grow another cylinder off the original crankcase, and hook both con-rods to the single, original crankpin. This gave twice the displacement, twice the power-with far fewer than twice the parts or bulk.

In the early days, revs were low (like 1200), so vibration was less important than smooth power flow. In a V-Twin, vibration is at a minimum at a V-angle of 90 degrees, and increases as the angle is made smaller. But power flow is at its smoothest at a V-angle of zero (360 degree firing order), and becomes more asymmetrical as the angle increases (in a 90-degree engine, the bangs come at a very staggered 270450-degree interval). Therefore, the early V-Twins had their cylinders set as close as their base flanges would allow—42 degrees in the case of the Indian. This was also handy in fitting the engine into existing diamond frames; the V-angle was about the same as the angle between the front down tu be and the seat tube.

The staggered firing of a V-Twin is also responsible for the special irregular sound that appeals to so many people, suggestive of muscular, big V-Eights or giant aircraft radiais.

Here in the Land of Plenty, there was no shortage of fuel, so engines could be as big as ambition. U.S.-built motorcycles therefore never had a fuel or tax incentive to rev up as a means of extracting adequate power from too little displacement. They remained large, slow-turning prime movers that could afford the mild cams that give muscle at every speed, without vice. Gearchanging was something you did only to get up to speed. Once in top gear, riders liked to leave it there and climb hills on the throttle alone. Crank and rods ran on roller bearings because rolling bearings could survive best in the early, total-loss-lubed engines. When pressure lubrication came in 1933, the rollers stayed on.

Because 500cc, a half-liter, had been a common engine size for the first Singles, early Twins were just twice that: 61 cubic inches. From that size to the 74 inches of this Chief was a small jump. Bore/stroke were 3 1/4 x 4 7/16 inches (82.5 x 1 12.7mm)-small bore, very long stroke—proportions inherited from steam engines. Although many believe to this day that a long stroke “makes torque,” the real reason such engines have good low-speed power is the small size of their valves; the smaller the valves, the lower the rpm of peak breathing efficiency.

Phis Chief is a flathead, which sounds primitive in our world of overhead-cam, four-valve engines. Yes, it’s true that when compression is above 6:1, the head is the only place with room for valves, but in the earliest days, with compression at 3:1, there was room in such a big combustion chamber to put valves almost anywhere-overhead, sticking out to the side, or next to the cylinder in flathead configuration. But the flathead was the first good solution to the problem of engine knock. With both valves at the side, stems downward, the piston could be brought very close to the head at TDC, squeezing out mixture into the main chamber above the valves in a fast-moving, turbulent jet. A turbulent flame speedily burned the charge before knock could develop. Lawnmower engines remain flatheads to this day-for the good reasons of knock resistance and stone-ax simplicity. Above 6:1 compression, there is no longer room for both adequate valve lift and flow area in a flathead design. The ohv design is the true path onward to more power-but what if you are happy with the wide, unfussy power of a big 74or 80-inch flattie?

The Chief engine was originally drawn by Charles B. Franklin for 1922, improved over the years by detachable heads (1925), increased cooling area and aluminum heads ( 1935-38). It was based upon tradition extending back to the founders, Hedstrom and Hendee. Indian was a technology leader at the beginning, pioneering the automatic carburetor (one in which the rider controlled only the airflow, and the fuel was automatically proportioned to suit), the three-speed gearbox, and many other advances. Indian machines swept the 1911 Isle of Man TT, defeated the famed Charlie Collier at England's Brooklands Speedway, and were powerfully influential in the many countries to which they were exported in the 1920s and '30s. Sadly, this once-dynamic maker became a financial football in the 1930s, then fumbled both wartime contracts and post-war marketing, perishing in 1953. No tradition, however illustrious, is permanent.

Kevin Cameron

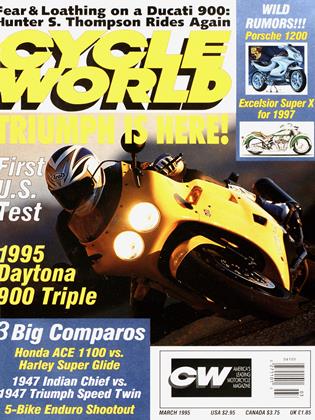

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Up Front

Up FrontRamblings

March 1995 By David Edwards -

Leanings

LeaningsMotorcycling For the Duration

March 1995 By Peter Egan -

TDC

TDCNo Sharp Corners

March 1995 By Kevin Cameron -

Letters

LettersLetters

March 1995 -

Roundup

RoundupPorsche Building A Bike?

March 1995 By Robert Hough -

Roundup

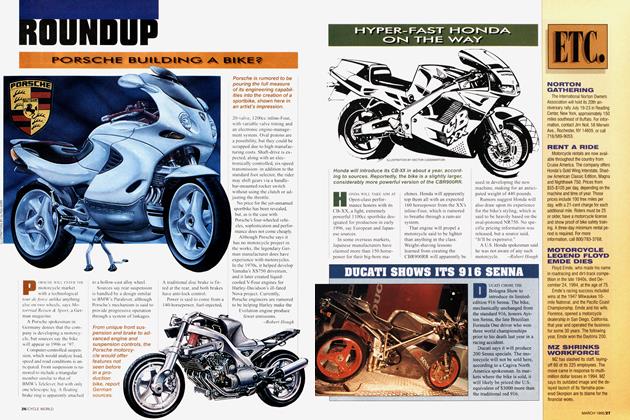

RoundupHyper-Fast Honda On the Way

March 1995 By Robert Hough