Motorcycling for the duration

LEANINGS

Peter Egan

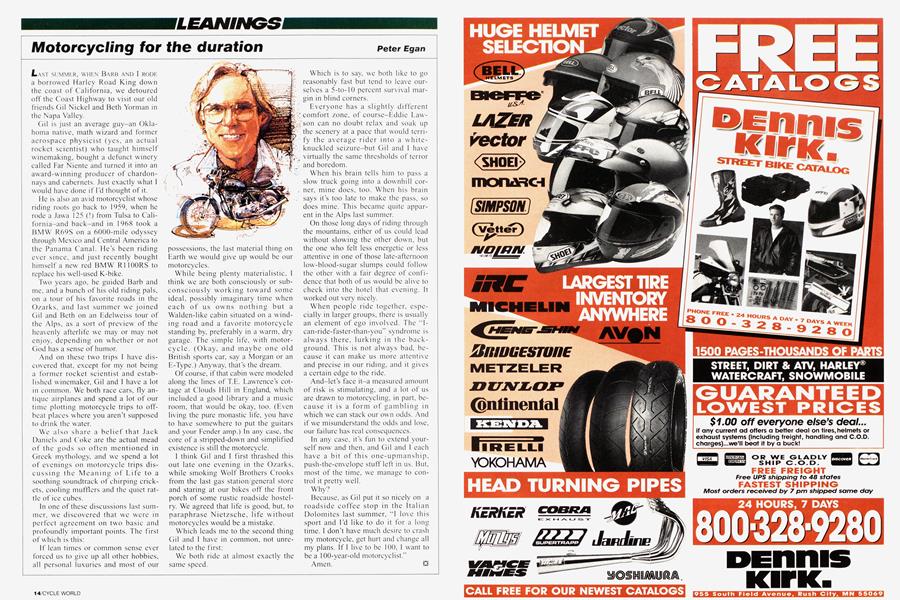

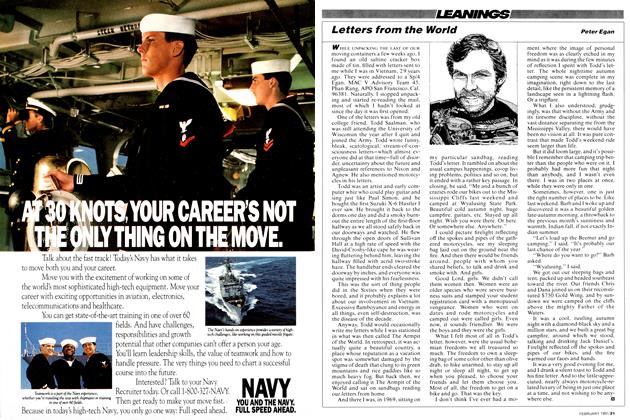

LAST SUMMER, WHEN BARB AND I RODE a borrowed Harley Road King down the coast of California, we detoured off the Coast Highway to visit our old friends Gil Nickel and Beth Yorman in the Napa Valley.

Gil is just an average guyߞan Oklahoma native, math wizard and former aerospace physicist (yes, an actual rocket scientist) who taught himself winemaking, bought a defunct winery called Far Niente and turned it into an award-winning producer of chardonnays and cabernets. .lust exactly what I would have done if I’d thought of it.

He is also an avid motorcyclist whose riding roots go back to 1959, when he rode a Jawa 125 (!) from Tulsa to California-and back-and in 1968 took a BMW R69S on a 6000-mile odyssey through Mexico and Central America to the Panama Canal. He’s been riding ever since, and just recently bought himself a new red BMW R1100RS to replace his well-used K-bike.

Two years ago, he guided Barb and me, and a bunch of his old riding pals, on a tour of his favorite roads in the Ozarks, and last summer we joined Gil and Beth on an Edelweiss tour of the Alps, as a sort of preview of the heavenly afterlife we may or may not enjoy, depending on whether or not God has a sense of humor.

And on these two trips I have discovered that, except for my not being a former rocket scientist and established winemaker, Gil and 1 have a lot in common. We both race cars, tly antique airplanes and spend a lot of our time plotting motorcycle trips to offbeat places where you aren’t supposed to drink the water.

We also share a belief that Jack Daniels and Coke are the actual mead of the gods so often mentioned in Greek mythology, and we spend a lot of evenings on motorcycle trips discussing the Meaning of Life to a soothing soundtrack of chirping crickets. cooling mufflers and the quiet rattle of ice cubes.

In one of these discussions last summer, we discovered that we were in perfect agreement on two basic and profoundly important points. The first of which is this:

If lean times or common sense ever forced us to give up all other hobbies, all personal luxuries and most of our possessions, the last material thing on Earth we would give up would be our motorcycles.

While being plenty materialistic, 1 think we are both consciously or subconsciously working toward some ideal, possibly imaginary time when each of us owns nothing but a Walden-like cabin situated on a winding road and a favorite motorcycle standing by. preferably in a warm, dry garage. The simple life, with motorcycle. (Okay, and maybe one old British sports car. say a Morgan or an E-Type.) Anyway, that’s the dream.

Of course, if that cabin were modeled along the lines of T.E. Lawrence’s cottage at Clouds Hill in England, which included a good library and a music room, that would be okay, too. (Even living the pure monastic life, you have to have somewhere to put the guitars and your Fender amp.) In any case, the core of a stripped-down and simplified existence is still the motorcycle.

I think Gil and 1 first thrashed this out late one evening in the Ozarks, while smoking Wolf Brothers Crooks from the last gas station/general store and staring at our bikes off the front porch of some rustic roadside hostelry. We agreed that life is good, but, to paraphrase Nietzsche, life without motorcycles would be a mistake.

Which leads me to the second thing Gil and I have in common, not unrelated to the first:

We both ride at almost exactly the same speed.

Which is to say, we both like to go reasonably fast but tend to leave ourselves a 5-to-10 percent survival margin in blind corners.

Everyone has a slightly different comfort zone, of course-Eddie Lawson can no doubt relax and soak up the scenery at a pace that would terrify the average rider into a whiteknuckled seizure-but Gil and 1 have virtually the same thresholds of terror and boredom.

When his brain tells him to pass a slow truck going into a downhill corner, mine does, too. When his brain says it's too late to make the pass, so does mine. This became quite apparent in the Alps last summer.

On those long days of riding through the mountains, either of us could lead without slowing the other down, but the one who felt less energetic or less attentive in one of those late-afternoon low-blood-sugar slumps could follow the other with a fair degree of confidence that both of us would be alive to check into the hotel that evening. It worked out very nicely.

When people ride together, especially in larger groups, there is usually an element of ego involved. The “Ican-ride-faster-than-you" syndrome is always there, lurking in the background. This is not always bad, because it can make us more attentive and precise in our riding, and it gives a certain edge to the ride.

And-lct's face it-a measured amount of risk is stimulating, and a lot of us arc drawn to motorcycling, in part, because it is a form of gambling in which we can stack our own odds. And if we misunderstand the odds and lose, our failure has real consequences.

In any case, it's fun to extend yourself now and then, and Gil and I each have a bit of this one-upmanship, push-the-envelope stuff left in us. But, most of the time, we manage to control it pretty well.

Why?

Because, as Gil put it so nicely on a roadside coffee stop in the Italian Dolomites last summer, “I love this sport and I'd like to do it for a long time. I don't have much desire to crash my motorcycle, get hurt and change all my plans. If I live to be 100. 1 want to be a 100-year-old motorcyclist."

Amen.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue