SPEED TWIN

TECH LOOK

EDWARD TURNER’S MASTERPIECE

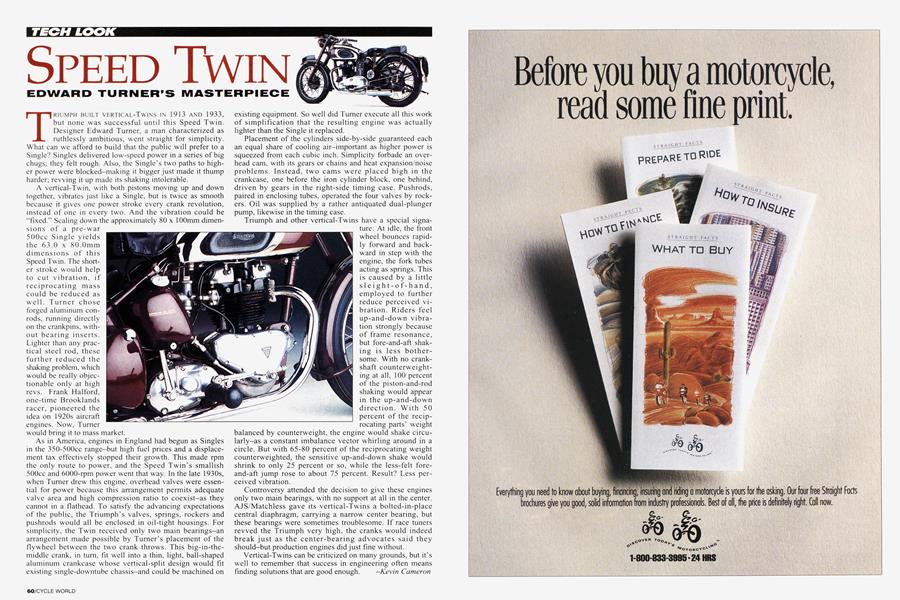

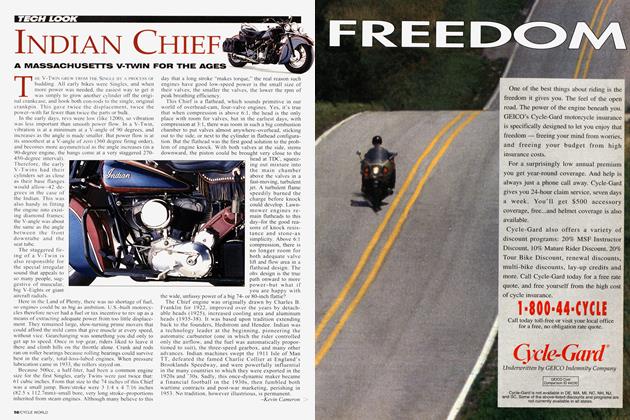

TRIUMPH BUILT VERTICAL-TWINS IN 1913 AND 1933, but none was successful until this Speed Twin. Designer Edward Turner, a man characterized as ruthlessly ambitious, went straight for simplicity.

What can we afford to build that the public will prefer to a Single? Singles delivered low-speed power in a series of big chugs; they felt rough. Also, the Single’s two paths to higher power were blocked-making it bigger just made it thump harder; revving it up made its shaking intolerable.

A vertical-Twin, with both pistons moving up and down together, vibrates just like a Single, but is twice as smooth because it gives one power stroke every crank revolution, instead of one in every two. And the vibration could be “fixed.” Scaling down the approximately 80 x 100mm dimen-

sions of a pre-war 500cc Single yields the 63.0 x 80.0 m m d i mensi ons of this Speed Twin. The shorter stroke would help to cut vibration, if reciprocating mass could be reduced as well. Turner chose forged aluminum conrods, running directly on the crankpins, without bearing inserts. Lighter than any practical steel rod, these further reduced the shaking problem, which would be really objectionable only at high revs. Frank Halford, one-time Brook lands racer, pioneered the idea on 1920s aircraft engines. Now, Turner would bring it to mass market.

As in America, engines in England had begun as Singles in the 35()-5()()cc range—but high fuel prices and a displacement tax effectively stopped their growth. This made rpm the only route to power, and the Speed Twin’s smallish 500cc and 6000-rpm power went that way. In the late 1930s, when Turner drew this engine, overhead valves were essential for power because this arrangement permits adequate valve area and high compression ratio to coexist-as they cannot in a fathead. To satisfy the advancing expectations of the public, the Triumph’s valves, springs, rockers and pushrods would all be enclosed in oil-tight housings. For simplicity, the Twin received only two main bearings-an arrangement made possible by Turner’s placement of the flywheel between the two crank throws. This big-in-themiddle crank, in turn, fit well into a thin, light, ball-shaped aluminum crankcase whose vertical-split design would fit existing single-downtube chassis-and could be machined on existing equipment. So well did Turner execute all this work of simplification that the resulting engine was actually lighter than the Single it replaced.

Placement of the cylinders side-by-side guaranteed each an equal share of cooling air-important as higher power is squeezed from each cubic inch. Simplicity forbade an overhead cam, with its gears or chains and heat expansion/noise problems. Instead, two cams were placed high in the crankcase, one before the iron cylinder block, one behind, driven by gears in the right-side timing case. Pushrods, paired in enclosing tubes, operated the four valves by rockers. Oil was supplied by a rather antiquated dual-plunger pump, likewise in the timing case.

Triumph and other vertical-Twins have a special signature: At idle, the front wheel bounces rapidly forward and backward in step with the engine, the fork tubes acting as springs. This is caused by a little sleight-of-hand, employed to further reduce perceived vibration. Riders feel up-and-down vibration strongly because of frame resonance, but fore-and-aft shaking is less bothersome. With no crankshaft counterweighting at all, 100 percent of the piston-and-rod shaking would appear in the up-and-down direction. With 50 percent of the reciprocating parts’ weight balanced by counterweight, the engine would shake circularly-as a constant imbalance vector whirling around in a circle. But with 65-80 percent of the reciprocating weight counterweighted, the sensitive up-and-down shake would shrink to only 25 percent or so, while the less-felt foreand-aft jump rose to about 75 percent. Result? Less perceived vibration.

Controversy attended the decision to give these engines only two main bearings, with no support at all in the center. AJS/Matchless gave its vertical-Twins a bolted-in-place central diaphragm, carrying a narrow center bearing, but these bearings were sometimes troublesome. If race tuners revved the Triumph very high, the cranks would indeed break just as the center-bearing advocates said they should-but production engines did just fine without.

Vertical-Twins can be criticized on many grounds, but it’s well to remember that success in engineering often means finding solutions that are good enough.

Kevin Cameron

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Up Front

Up FrontRamblings

March 1995 By David Edwards -

Leanings

LeaningsMotorcycling For the Duration

March 1995 By Peter Egan -

TDC

TDCNo Sharp Corners

March 1995 By Kevin Cameron -

Letters

LettersLetters

March 1995 -

Roundup

RoundupPorsche Building A Bike?

March 1995 By Robert Hough -

Roundup

RoundupHyper-Fast Honda On the Way

March 1995 By Robert Hough