Once Warriors

RACING ON THE 10-YEAR PLAN

KEVIN CAMERON

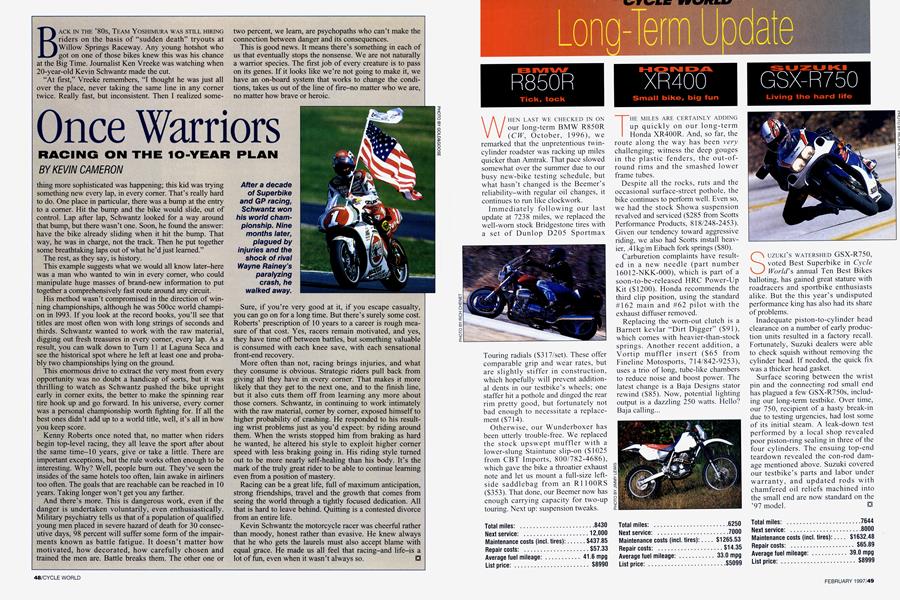

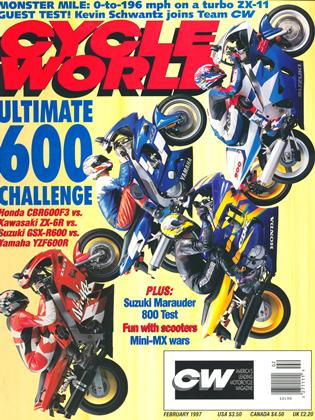

BACK IN THE `80s, TEAM YOSHIMURA WAS STILL HIRING riders on the basis of "sudden death" tryouts at Willow Springs Raceway. Any young hotshot who got on one of those bikes knew this was his chance at the Big Time. Journalist Ken Vreeke was watching when 20-year-old Kevin Schwantz made the cut.

"At first," Vreeke remembers, "I thought he was just all over the place, never taking the same line in any corner twice. Really fast, but inconsistent. Then I realized something more sophisticated was happening; this kid was trying something new every lap, in every corner. That's really hard to do. One place in particular, there was a bump at the entry to a corner. Hit the bump and the bike would slide, out of control. Lap after lap, Schwantz looked for a way around that bump, but there wasn't one. Soon, he found the answer: have the bike already sliding when it hit the bump. That way, he was in charge, not the track. Then he put together some breathtaking laps out of what he'd just learned."

The rest, as they say, is history. This example suggests what we would all know later-here was a man who wanted to win in every corner, who could manipulate huge masses of brand-new information to put together a comprehensively fast route around any circuit.

His method wasn't compromised in the direction of winfling championships, although he was 500cc world champi on in 1993. If you look at the record books, you'll see that titles are most often won with long strings of seconds and thirds. Schwantz wanted to work with the raw material, digging out fresh treasures in every corner, every lap. As a result, you can walk down to Turn 11 at Laguna Seca and see the historical spot where he left at least one and proba blytwo championships lying on the ground. -

This enormous drive to extract the very most from every opportunity was no doubt a handicap of sorts, but it was thrilling to watch as Schwantz pushed the bike upright early in corner exits, the better to make the spinning rear tire hook up and go forward. In his universe, every corner was a personal championship worth fighting for. If all the best ones didn't add up to a world title, well, it's all in how you keep score.

Kenny Roberts once noted that, no matter when riders begin top-level racing, they all leave the sport after about the same time-l 0 years, give or take a little. There are important exceptions, but the rule works often enough to be interesting. Why? Well, people burn out. They've seen the insides of the same hotels too often, lain awake in airliners too often. The goals that are reachable can be reached in 10 years. Taking longer won't get you any farther.

And there's more. This is dangerous work, even if the danger is undertaken voluntarily, even enthusiastically. Military psychiatry tells us that of a population of qualified young men placed in severe hazard of death for 30 consec utive days, 98 percent will suffer some form of the impair ments known as battle fatigue. It doesn't matter how motivated, how decorated, how carefully chosen and trained the men are. Battle breaks them. The other one or two percent, we learn, are psychopaths who can't make the connection between danger and its consequences.

This is good news. It means there's something in each of us that eventually stops the nonsense. We are not naturally a warrior species. The first job of every creature is to pass on its genes. If it looks like we're not going to make it, we have an on-board system that works to change the condi tions, takes us out of the line of fire-no matter who we are, no matter how brave or heroic.

Sure, if you're very good at it, if you escape casualty, you can go on for a long time. But there's surely some cost. Roberts' prescription of 10 years to a career is rough mea sure of that cost. Yes, racers remain motivated, and yes, they have time off between battles, but something valuable is consumed with each knee save, with each sensational front-end recovery.

More often than not, racing brings injuries, and what they consume is obvious. Strategic riders pull back from giving all they have in every corner. That makes it more likely that they get to the next one, and to the finish line, but it also cuts them off from learning any more about those corners. Schwantz, in continuing to work intimately with the raw material, corner by corner, exposed himself to higher probability of crashing. He responded to his result ing wrist problems just as you'd expect: by riding around them. When the wrists stopped him from braking as hard he wanted, he altered his style to exploit higher corner speed with less braking going in. His riding style turned out to be more nearly self-healing than his body. It's the mark of the truly great rider to be able to continue learning even from a position of mastery.

Racing can be a great life, full of maximum anticipation, strong friendships, travel and the growth that comes from seeing the world through a tightly focused dedication. All that is hard to leave behind. Quitting is a contested divorce from an entire life.

Kevin Schwantz the motorcycle racer was cheerful rather than moody, honest rather than evasive. He knew always that he who gets the laurels must also accept blame with equal grace. He made us all feel that racing-and life-is a lot of fun, even when it wasn't always so.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue