The Death of T. E. Lawrence

They called him Lawrence of Arabia. He was a soldier, an artist, an enigma. And how he loved motorcycles.

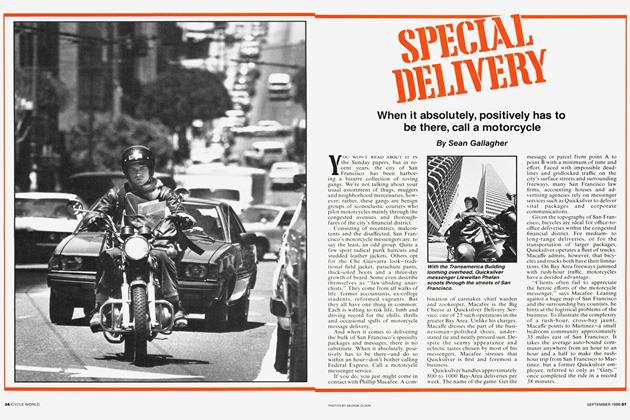

SEAN GALLAGHER

TO THIS DAY, EXACTLY WHAT HAPPENED ON THE morning of May 13, 1935, remains a mystery.

According to eyewitness accounts, the accident occurred on a lonely stretch of English road between the East Dorset villages of Wool and Clouds Hill. Corporal Earnest Catchpole, the principal witness, said he saw a black car, two bicycles and a motorcycle simultaneously enter a series of rises and depressions that follow the contour of the Clouds Hill end. A moment later he heard the noise of a crash, and the riderless motorcycle appeared, skidding over the crest of the nearest rise. After arriving at the scene, Catchpole found the motorcyclist lying in a pool of blood, and subsequently halted a passing army truck, which rushed the injured rider to the camp hospital at neighboring Bovington Army Barracks. The victim never regained consciousness, and died six days later with complications resulting from a compound skull fracture and a brain hemorrhage.

As is the custom on English country roads, a small white cross was erected at the scene of the fatal accident. What distinguishes this cross from the thousands of others that

dot the English countryside, however, is the victim it commemorates—Thomas Edward Lawrence, also known as Lawrence of Arabia.

Winston Churchill called Lawrence “one of the greatest beings of our time.” His most sedulous critic, writer Richard Aldington, maintained that Lawrence was an unimportant man, who shot unimportant holes in unimportant water towers.

Who was this man who achieved international acclaim in his youth, and died after crashing his Brough Superior in the remote East Dorset countryside? For more than 50 years this question has inspired both sympathetic biographies and venemous attacks. Yet, despite the efforts to separate the man from the myth, Lawrence remains one of the most misunderstood and mysterious figures of our century.

The search for the real T.E. Lawrence is nothing new. Lawrence himself conducted it all his life, and never found a satisfactory answer. There was no one answer, for there was no one Lawrence. He was a bundle of contradictions, or, as filmmaker David Lean claimed, “an alternating current with a negative for every positive.” Lawrence was a sensitive artist and a calloused soldier; a born leader and a compulsive recluse; an idealist and a cynic. Most importantly, he was at once a man torn by conflicting passions, and a living legend veiled in intrigue. And in the final irony, the mysterious circumstances of his death reflect the rumor and intrigue of his life.

The second of five illegimate sons, Lawrence was born to a scandalous English sportsman who settled in Oxford after abandoning his lawful wife and four legitimate daughters. Despite its questionable beginnings, the family led a comfortable life, and young Lawrence thrived in the academic enviromment. He achieved distinction as an Oxford scholar, and in later years developed a reputation as a leading authority on medieval architecture. He seemed

‘When hejound it necessary to relive the excitement and danger he had experienced in Palestine, motorcycles< filled the

destined to lead the academic life, content to fill his years with archeological expeditions to Palestine and wordy dissertations on crusader castles.

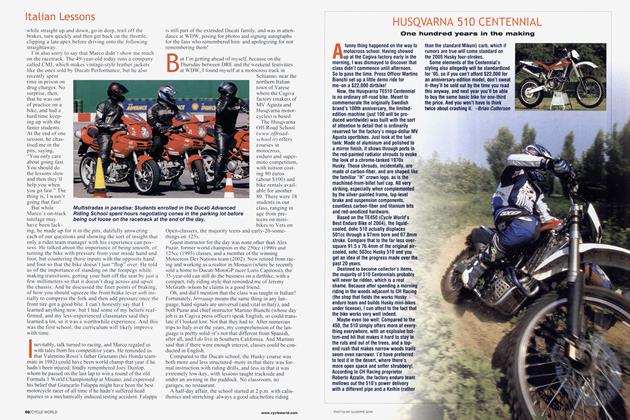

World War I changed all that. Commissioned as a subaltern, Lawrence reluctantly set to work in the backwaters of the war, preparing maps of the strategically important Sinai Peninsula. A cocksure young officer who terrorized the streets of Cairo on a second-hand Triumph, he was regarded with a certain disdain by senior officers of the British High Command. He was a sloppy soldier, careless about his uniform and impertinent to a fault. But his knowledge of the Middle East and his affinity for Arab customs and culture were unsurpassed. As a result, in 1916 he was assigned to lead the Arab Legion in revolt against the Turks.

This was no unimportant assignment for Lawrence. The Turks, who had joined forces with Germany, had displaced thousands of native Bedouins and were in control of a large portion of the Middle East, and had begun to threaten British control of the vital Suez Canal. The Bedouins, however, were, by nature, raiders and looters divided by traditional tribal loyalties, and unsuited to fighting as a disciplined army.

Somehow, Lawrence was able to successfully convince the feuding tribes to unite in a common cause, and the 20month drive toward Damascus began. The Arabs fought fiercely, but it was the charismatic Lawrence who turned chaos into victory by developing a campaign of hit-andrun tactics tailored to the raider temperament of his troops. Dressed in the princely robes of a desert sheik, he led savage assaults on Turkish supply lines and garrisons. Between raids, he often slipped into disguises and wandered alone deep into Turkish territory, scouting possible targets. By and large, he almost single-handedly assured victory.

Btbm................... IIT WHILE THE YOUNG ENGLISHMAN’S CAMPAIGN

was valuable in its own theater, it had little consequence in the total scale of World War I. And it was only the efforts of a young Princeton instructor named Lowell Thomas that transformed Lawrence from an unknown desert raider into a world-renowned legend. Thomas arrived on the European front in 1917 on a propaganda mission, but, after hearing wild rumors about the Arab revolt and its young English leader, left for Palestine to catalog the adventures of T.E. Lawrence. Thomas soon retuned to America with embellished accounts of Lawrence’s exploits in Palestine. The lecture series, “With Allenby and Lawrence in Palestine,” was an overnight success, as warweary audiences, hungry for tales of daring and adventure, marveled at the dashing Englishman who quickly became known as “the uncrowned king of the desert.”

Three years later, while lecture audiences were still discovering the legendary Lawrence of Arabia, the fallible T.E. Lawrence had slipped discreetly from the public arena. Colonel Lawrence, famed leader of the Arab Legion, had changed his name to John Hume Ross, and

joined the Royal Air Force as a lowly airman. He was assigned to the RAF’s Cadet College, where he maintained the aircraft in which student pilots were trained.

Of course, Lawrence’s identity didn’t remain secret for long, and soon, the school’s instructors were vying for the chance to take him flying. But while many of them must have expected a warrior king dressed in flowing robes, what they found instead was a taciturn, 5-foot-6 man who wished only to be left alone with his books and his beloved Brough, “to forget and be forgotten,” to erase his name from the public consciousness.

NéJÊtm Ir OBODY KNOWS THE REASON FOR LAWRENCE’S SELF-

imposed seclusion. There were rumors that he had been offered the exalted post of Governor of Egypt and had refused it. Churchill declared that the “greatest employments” were open to him; yet, Lawrence chose to spend the next 10 years of his life serving in England and India, refusing all rank and promotion. “Lawrence is one of those beings whose pace of life is faster and more intense than what is normal,” opined Chruchill. “He could only fly in a hurricane. He was out of harmony with the normal, and when the storm wind stopped, he could only with difficulty find a reason for existence. In a religious age, and if Lawrence had been a religious man, the monastery would have been his refuge. A harder task was reserved for him. He found it in the RAF.”

Alone in his RAF barracks, Lawrence adjusted to his self-imposed seclusion by writing several autobiographies and scholarly pieces. But when he found it necessary to relive the excitement and danger he had experienced in Palestine, motorcycles filled the void.

In the post-war years, Lawrence had a total of eight bikes built just for him by George Brough, the manufacturer of Brough Superior motorcycles. He gave his Broughs a succession of royal titles—George / through George VII in tribute to the machines’ builder. George VII, which was completed shortly before Lawrence’s death, was never delivered, and Brough kept the motorcycle as a personal reminder of his departed friend.

The JAP-engined Brough Superiors eafned distinction on the British racing circuit in the 1920s and 1930s, and Brough owners developed a fierce brand of loyalty for the machines. Lawrence was no exception: “A skittish Brough with a touch of blood in it is better than all the riding animals on earth,” he once said.

ACCORDING TO BROUGH, LAWRENCE WAS A CON-

scientious rider ... to a point. “I am able to state with conviction,” Brough wrote, “that T.E.L. was most considerate to every other road user. I never saw him take a single risk nor put any other rider or driver at the slightest inconvenience. But when the road was clear ahead, it required a

“All his life, he tried to drive himself harder, push his camel farther, ride his motorcycle, faster than any other man”

very good and experienced rider to keep anywhere near T.E.L.”

A fine rider perhaps, but when the road was clear ahead, the accident-prone Lawrence often overstepped his bounds. Once, while in the Arab Legion, Lawrence had distinguished himself during battle by shooting his own camel in the back of its head. The beast’s death plunge hurled him into the midst of the Turks, who were too stunned to kill or capture him. On motorcycles, Lawrence rode with the same vigor, and totaled at least three of his Broughs in almost as many years.

But the prospect of an occasional accident did little to diminish Lawrence’s enthusiasm for the sport. Speed itself gave him an obvious narcotic pleasure: “When I open out a little more, as for instance across the Salisbury Plain at 80 or so, I feel the earth molding herself under me. It is me piling up this hill, hollowing out this valley, stretching out this level place. Almost the earth comes alive, heaving and tossing on each like a sea. That is a thing that the slow coach will never feel. It is the reward of speed. I could write pages on the lustfulness of moving swiftly. Speed is the second oldest craving in our nature.”

U

NDENIABLY, LAWRENCE LAUNCHED HIMSELF AT

physical challenges with unusual zeal. He loved to endure hardship, sometimes to the point of absurdity. All his life, he tried to drive himself harder, push his camel farther, ride his motorcycle faster than any other man.

But although there was a strong element of competitiveness in Lawrence’s character, his fascination with motorcycles also had a deeper, darker significance. “When my mood gets too hot and I find myself wandering beyond control,” he once said, “I pull out my motorcycle and hurl it top-speed through these unfit roads for hour after hour. My nerves are jaded and gone near dead, so that nothing short of voluntary danger will prick them back to life.” With this kind of attitude, it was only his skill, and perhaps an element of luck, that kept Lawrence from serious injury. But on May 13, 1935, that luck ran out.

Lawrence’s last accident occurred about a month after he had left the RAE A friend had somehow developed the idea that Lawrence was just the man to talk some sense into Adolf Hitler, and had requested a meeting to discuss the project. Agreeing at least to the meeting, Lawrence dashed to the Wool Post Office from his Clouds Hill cottage, and sent a message fixing the appointment for the following Tuesday. The Postmaster stamped the telegram at precisely 11:35, and Lawrence left Wool, roaring home flat-out as usual.

He never made it.

LTHOUGH THE EAST DORSET CORONER RECOM-

mended a verdict of accidental death, he admitted that there were some unsatisfactory features to the inquest. Chief witness Catchpole, by his own admission, noted that the details regarding the accident were not absolutely clear. Judging from the sound of the motorcycle, the good corporal had estimated that the speed of the bike was between 50 and 60 mph. In contrast, another witness, Pat Knowles, said he heard the motorcycle downshift twice. Later investigation revealed that the Brough was jammed in second gear, and as a result, could not have beeen traveling over 38 mph.

Other inconsistencies surfaced when Frank Fletcher, one of the two boy cyclists, gave evidence. Contrary to Catchpole’s testimony, Fletcher maintained that no black car had been present. When he heard the sound of a motorcycle approaching from the rear, Fletcher, who had been riding abreast of the other cyclist, changed to single file. Shortly after, Fletcher heard the sound of a crash, and was then knocked over by his companion’s bicycle. Fletcher then saw Lawrence hit the ground approximately five yards from his motorcycle, which was in turn five yards from where Fletcher had fallen.

With the addition of Fletcher’s testimony, the inquest determined that Lawrence had probably met the black car coming out of the depression as he was about to enter it. The road was quite narrow at this point, and as the two vehicles approached, Lawrence must have pulled over to the left-hand side. On doing so, he would have seen the two bicyclists directly in his path, and in swerving to avoid them he must have lost control, his skidding machine sideswiping the second bicyclist. Judging from the injuries, the inquest surmised that Lawrence had been thrown over the handlebars and had landed on his head.

Apparently satisfied, the inquest concurred with the coroner’s recommendation, and delivered a verdict of accidental death. No attempt was made to find the driver of the mysterious black car, and no attempt was made to resolve the contradictory evidence.

The public, dissatisfied with the official report, made up their own. A close friend was convinced that Lawrence had been blinded by a bee. Others claimed that the mysterious black car had intentionally forced Lawrence off the road. There were, of couse, the standard rumors of suicide and scores of other explanations, but the real questions of Lawrence’s life and death were then, as now, misted in intrigue. Was he genuinely a heroic figure, or merely the product of Lowell Thomas’s propaganda? Why did this man, who could have built empires, spurn all honor and die in self-imposed seclusion? And, on the day of his fatal accident, was the 46-year-old Lawrence making plans to return to the political arena?

p

ÆL IFT'i

IFTY YEARS LATER, WE FIND OURSELVES ASKING THE

same questions, and still, we have no conclusive answers. But, in the final analysis, it is a fitting tribute that the mystery, rumor and controversy that surrounded Lawrence in life should continue long after his death. [g

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Departments

DepartmentsEditorial

December 1986 By Paul Dean -

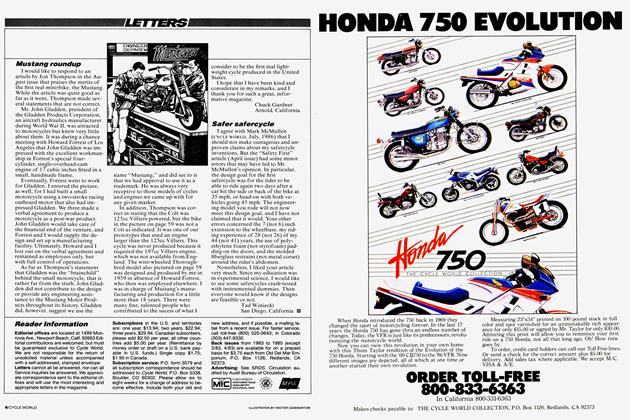

Letters

LettersLetters

December 1986 -

Roundup

RoundupWatching Them Watch the Show: Cologne '86

December 1986 By David Edwards -

Roundup

RoundupLetter From Japan

December 1986 By Koichi Hirose -

Roundup

RoundupLetter From Europe

December 1986 By Alan Cathcart -

1987 Previews And Riding Impressions

1987 Previews And Riding Impressions1987 New Model Preview

December 1986