WAR ON WHEELS

A short history of olive-drab motorcycles

SEAN GALLAGHER

IN 1898, A MILITARY VISIONARY BY THE NAME OF ROYAL Davidson built one of the earliest motor vehicles designed exclusively for military service. A professor of military tactics, Davidson modified a three-wheeled automobile by mounting protective armor plating and a 45-caliber machine gun. Self-important cavalry officers of the time scoffed at the contraption, seeing little practical value in the military applications of the internal-combustion engine.

By 1914, however, the climate had changed. With the battle lines drawn for World War I, cavalry officers still relied on tactics and strategies of a previous age. But in practice, the horse-mounted rifleman was reduced to incompetence by long lines of entrenchments, barbed-wire entanglements and airborne surveillance. It soon became apparent that machines rather than horses were more suited to rigors of the battlefield; and for the first time in history, motorcycles became a factor of critical importance in the success or failure of warring nations.

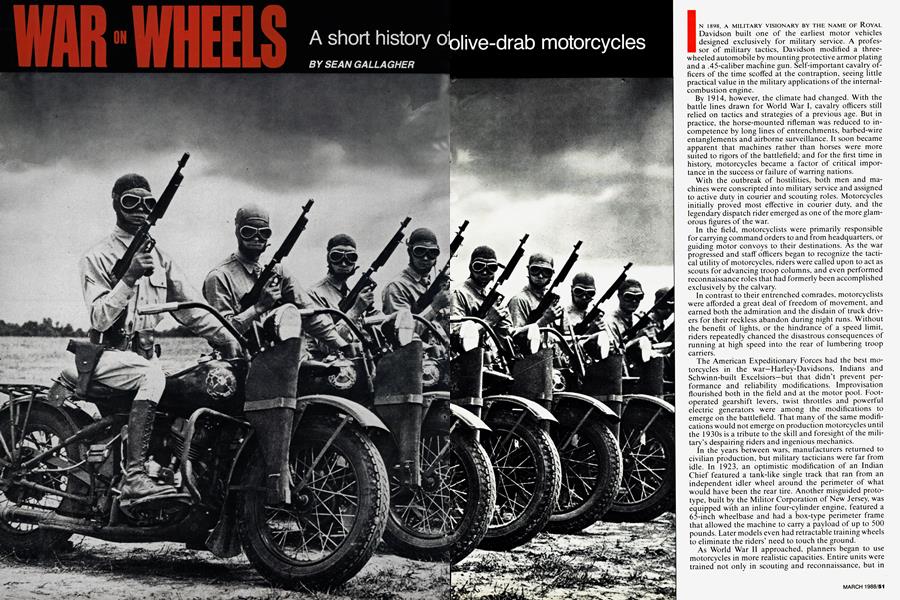

With the outbreak of hostilities, both men and machines were conscripted into military service and assigned to active duty in courier and scouting roles. Motorcycles initially proved most effective in courier duty, and the legendary dispatch rider emerged as one of the more glamorous figures of the war.

In the field, motorcyclists were primarily responsible for carrying command orders to and from headquarters, or guiding motor convoys to their destinations. As the war progressed and staff officers began to recognize the tactical utility of motorcycles, riders were called upon to act as scouts for advancing troop columns, and even performed reconnaissance roles that had formerly been accomplished exclusively by the calvary.

In contrast to their entrenched comrades, motorcyclists were afforded a great deal of freedom of movement, and earned both the admiration and the disdain of truck drivers for their reckless abandon during night runs. Without the benefit of lights, or the hindrance of a speed limit, riders repeatedly chanced the disastrous consequences of running at high speed into the rear of lumbering troop carriers.

The American Expeditionary Forces had the best motorcycles in the war-Harley-Davidsons, Indians and Schwinn-built Excelsiors-but that didn’t prevent performance and reliability modifications. Improvisation flourished both in the field and at the motor pool. Footoperated gearshift levers, twist throttles and powerful electric generators were among the modifications to emerge on the battlefield. That many of the same modifications would not emerge on production motorcycles until the 1930s is a tribute to the skill and foresight of the military’s despairing riders and ingenious mechanics.

In the years between wars, manufacturers returned to civilian production, but military tacticians were far from idle. In 1923, an optimistic modification of an Indian Chief featured a tank-like single track that ran from an independent idler wheel around the perimeter of what would have been the rear tire. Another misguided prototype, built by the Militor Corporation of New Jersey, was equipped with an inline four-cylinder engine, featured a 65-inch wheelbase and had a box-type perimeter frame that allowed the machine to carry a payload of up to 500 pounds. Later models even had retractable training wheels to eliminate the riders’ need to touch the ground.

As World War II approached, planners began to use motorcycles in more realistic capacities. Entire units were trained not only in scouting and reconnaissance, but in assault tactics, as well. Since a bike’s low profile offered a comparatively small target to enemy gunners, tacticians believed motorcycle assault teams would have an advantage over more-conventional vehicles in desert raiding and flanking maneuvers. The men would ride into battle heavily armed with grenades and submachine guns, the latter housed in frame-mounted holsters. During active engagement, the soldiers would dismount and use the bikes for cover.

Just prior to Pearl Harbor there was much interest in motorcycles. The Crosley Company of Cincinnati, for instance, eager to earn the lucrative benefits of Army contracts, offered a prototype that entertained unique notions for the time. The rear fender doubled as a gas tank, and although the prototype featured a conventional front fork assembly, the shaft-driven Crosley was equipped with a single-sided swingarm to facilitate speedy tire changes. A later prototype even had a sturdy, single-sided front fork mounted on the left side, presumably to offset the swingarm mounted on the right side. Although the Crosley employed several innovative ideas, the prototypes, as was the case with many other experimental motorcycles, were never really developed beyond the testing stage.

During World War II, a total of 300,000 American motorcycles were manufactured for the military, the majority of which were Harley-Davidson WLAs. With a top speed of 85 mph, the 750cc Harleys outperformed their contemporaries on the road and earned distinction throughout the European theater. The durable Harleys even found their way into the Imperial Japanese Army. Prior to the war, Harley-Davidson had manufactured motorcycles in Japan under the name Rikuo, and with the declaration of hostilities, the plant was seized by the state and operations were converted to wartime production.

While the WLA’s relatively high power output made the bike ideal for behind-the-lines administrative duties, the days of military motorcycles were numbered. As the war moved towards its conclusion, improvements in portable radios eliminated the need for dispatch riders, and Jeeps proved more effective than two-wheeled assault teams and sidecar machine-gun platforms. Army motorcyclists increasingly found themselves relegated to administrative and police functions. And by the 1950s, motorcycles had all but disappeared from the U.S. armed forces.

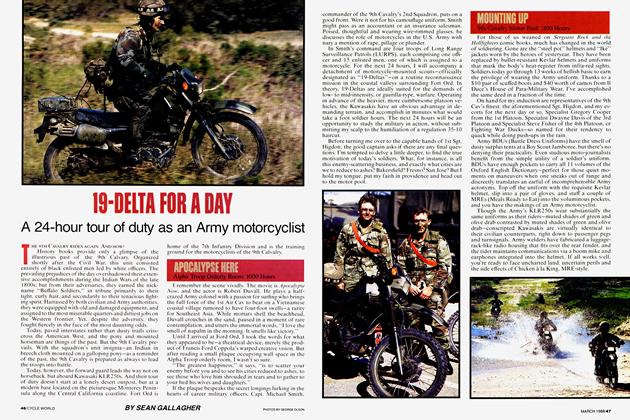

Today, only mounted scouts remain as an operational element of modern divisions. And Army riders assigned to the 7th Infantry Division carry out their duties aboard Kawasaki KLR250s. Lightweight and far more maneuverable than the Harley WLAs of the previous generation, the KLRs fulfill the demands of specialized reconnaissance in guerilla warfare situations. But since there is no longer a need for the dash and daring of the dispatch rider or the bravado of the motorized assault teams, the glory days of military motorcycles are long-gone . . . but certainly not forgotten. E3

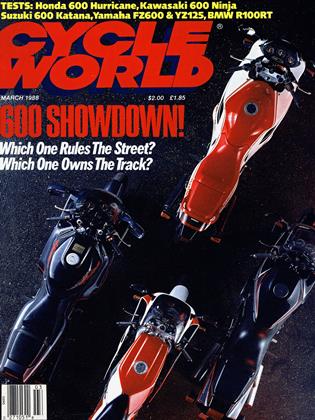

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Departments

DepartmentsEditorial

March 1988 By Steve Anderson -

Departments

DepartmentsLeanings

March 1988 By Peter Egan -

Letters

LettersLetters

March 1988 By Hector Cademartori -

Roundup

RoundupThe Perfect Motorcycle

March 1988 By Camron E. Bussard -

Roundup

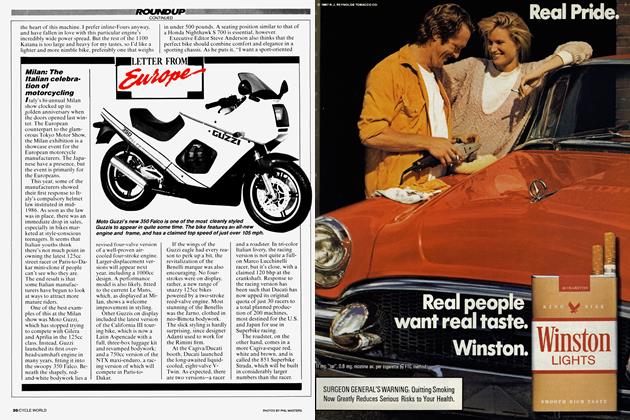

RoundupLetter From Europe

March 1988 By Alan Cathcart -

Roundup

RoundupDestinations

March 1988 By David Edwards