SPECIAL DELIVERY

When it absolutely, positively has to be there, call a motorcycle

Sean Gallagher

YOU WON'T READ ABOUT IT IN the Sunday papers, but in recent years, the city of San Francisco has been harboring a bizarre collection of roving gangs. We're not talking about your usual assortment of thugs, muggers and neighborhood mercenaries, however; rather, these gangs are benign groups of iconoclastic couriers who pilot motorcycles mainly through the congested avenues and thoroughfares of the city's financial district.

Consisting of eccentrics, malcontents and the disaffected. San Francisco’s motorcycle messengers are, to say the least, an odd group. Quite a few sport radical punk haircuts and studded leather jackets. Others opt for the Che Guevarra look—traditional field jacket, parachute pants, thick-soled boots and a three-day growth of beard. Some even describe themselves as “law-abiding anarchists.” They come from all walks of life: former accountants, ex-college students, reformed vagrants. But they all have one thing in common: Each is willing to risk life, limb and driving record for the chills, thrills and occasional spills of motorcycle message delivery.

And when it comes to delivering the bulk of San Francisco’s specialty packages and messages, there is no substitute. When it absolutely, positively has to be there—and do so within an hour—don’t bother calling Federal Express. Call a motorcycle messenger service.

If you do, you just might come in contact with Phillip Macafee. A combination of caretaker, chief warden and zookeeper, Macafee is the Big Cheese at Quicksilver Delivery Service, one of 25 such operations in the greater Bay Area. Unlike his charges, Macaffe dresses the part of the businessman-polished shoes, understated tie and neatly pressed suit. Despite the seamy appearance and eclectic tastes chosen by most of his messengers, Macafee stresses that Quicksilver is first and foremost a business.

Quicksilver handles approximately 800 to 1000 Bay-Area deliveries per week. The name of the game: Get the message or parcel from point A to point B with a minimum of time and effort. Faced with impossible deadlines and gridlocked traffic on the city's surface streets and surrounding freeways, many San Francisco law firms, accounting houses and advertising agencies rely on messenger services such as Quicksilver to deliver vital packages and corporate communications.

Given the topography of San Francisco, bicycles are ideal for office-tooffice deliveries within the congested financial district. For mediumto long-range deliveries, or for the transportation of larger packages, Quicksilver operates a fleet of trucks. Macaffe admits, however, that bicycles and trucks both have their limitations. On Bay Area freeways jammed with rush-hour traffic, motorcycles have a decided advantage.

“Clients often fail to appreciate the heroic efforts of the motorcycle messenger,” says Macafee. Leaning against a huge map of San Francisco and the surrounding bay counties, he hints at the logistical problems of the business. To illustrate the complexity of a rush-hour, cross-bay jaunt, Macaffe points to Martinez—a small bedroom community approximately 35 miles east of San Francisco. It takes the average auto-bound commuter anywhere from an hour to an hour and a half to make the rushhour trip from San Francisco to Martinez; but a former Quicksilver employee, referred to only as “Gary,” once completed the ride in a record 38 minutes.

According to Macafee, Gary typifies the hard-core motorcycle messenger. Many of them view themselves as free-spirited visionaries, and embrace a somewhat bohemian lifestyle. Because San Francisco has always welcomed eccentrics, it is no surprise that many messengers don't just find a home in this city, but also find themselves being accepted. As a result, many of them have a fanatical dedication to the city.

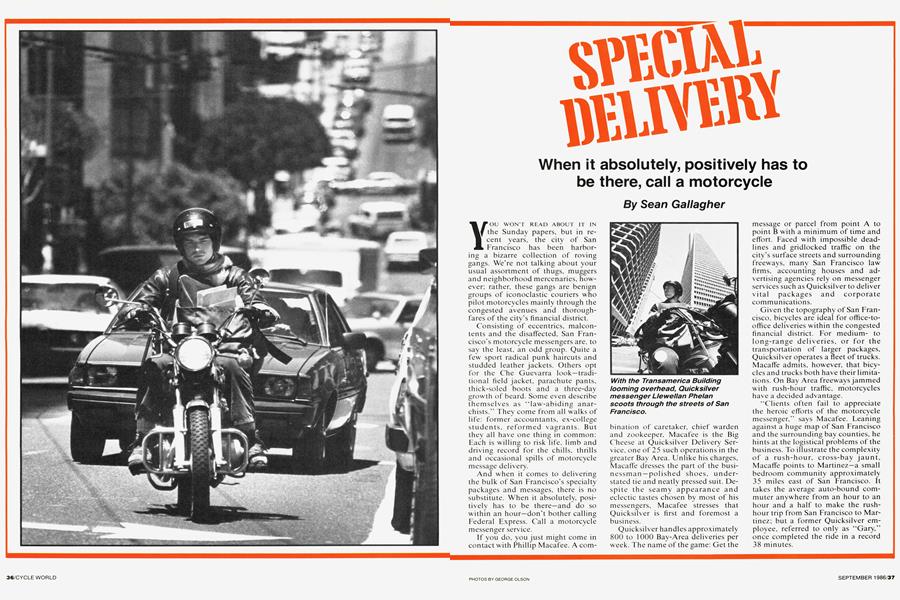

Llewellan Thomas Phelan is no exception. Phelan is a drifter, the product of a restless generation. A former Ivy Leaguer who migrated west, he graduated from the University of California at Berkeley with a degree in Philosophy. After graduation, he attended Lincoln School of Law in San Francisco, but not for long. After completing a year of study, Phelan exchanged his student’s motorboard for a leather jacket and a battered helmet; his case briefs and law books for an aging Honda 550 Four. He became a motorcycle messenger.

Phelan looks the part—a careful orchestration of windblow n hair, baggy trousers and the world-weary smile of a seasoned street veteran. Between runs, he retires to Quicksilver's Beale Street headquarters; there, in the shadow s of San Francisco's towering financial district, he submits to the messenger’s daily routine—thumbing through the day’s receipts, taking careful note of the mileage, calculating his wages.

Phelan insists that motorcycle couriers are a vital element of San Francisco’s vast messenger sub-culture, but admits that they are often overlooked. And nothing illustrates Phelan’s concern more graphically than Quicksilver, a movie released earlier this year that uses the same name as the San Francisco delivery service. The film charts the adventures of a securities-trader-turned-bicycle-messenger. but manages only a tenuous balance between credibility and pure fabrication. But even though Phelan found the plot twodimensional, he admits that it did succeed in publicizing the messenger industry. Still, Phelan considers the absence of motorcycles in the movie inexcusable.

“Quicksilver completely failed to acknowledge the motorized aspect of the business,” says Phelan. “There's another dimension out there, a world where leather-clad fools course through the howling canyons of New Montgomery and Market, connecting every important group, company and individual in this city. We use every street, sidewalk and alley of this city. And if use is ownership, then we own San Francisco.”

Outlandish claims and behavior are not unique to San Francisco’s moto-messengers. In London, determined dispatch riders wage a relentless war against “lorries” and passenger-laden double-decker buses. Across the Irish Sea, “Pony Express” messengers rival legions of Guarda and armies of meter-maids for the control of Grafton and O'Connell streets. Even in New York, where obnoxious cabbies once reigned supreme, motorcycle messengers now shoulder the burden of spitting on the sidewalk and swearing at tourists. But only in San Francisco can the motorcycle messenger claim undisputed ownership.

According to Phelan, some San Francisco messengers stake out their turf on the latest in Japanese exotica—Ninjas, GSX-Rs and FJ 1 100s— but the “serious” messenger necessarily takes a minimalistic approach. “There’s nothing aesthetic about this business at all,” he claims. “We use thrashed machines —old Japanese workhorses—that get the job done.”

Phelan pauses for a moment as he fumbles with an uncooperative helmet strap. It's time to reclaim the financial district from the accoun tants, lawyers and advertising execu tives who have undoubtedly emerged from the barricades in Phelan's ab sence. "I may quite literally die in this city," he says with a melodra matic note of foreboding, "but hap pily so."

ín wearing a helmet, Phelan exhibits unusual discretion for a San Francisco messenger. The majority of his colleagues live up to the courier's well-deserved reputation for throwing caution to the winds. Each business day, as many as 500 messengers take to the streets on bicycles, scooters and motorcycles. Like hungry club racers chasing the promise of factory contracts, they slice purposefully through the thickest swarms of autos, ignoring traffic lights, unwary pedestrians and posted speed limits.

Macafee is quick to point out that Quicksilver discourages such behavior. “There are some instances when we have to go the extra mile for a client, but overall, we don't advocate reckless driving.” He also notes that Quicksilver’s safety record speaks for itself: no moving violations and no accidents in the past two years.

But not all San Francisco delivery services can make similar claims. Since most messengers work on com mission, earning as much as $400 per week, they insist that an aggressive riding style is necessary to meet dead lines and make a profit. And tradi tionally. San Francisco's messengers have enjoyed relative immunity from traffic laws; but when a 4-year-old boy was run over and injured last year by a motorcycle messenger, the police department initiated a get tough policy. In the months that fol lowed the incident, more than 300 citations were issued.

Captain Charles Beene, commandins officer of the San Francisco Po lice Department's Honda Unit, cred its his motorcycle corps with the success of the crackdown. Straddling one of the department's 18 Honda XL25Os, Beene says, `1 understand that the kids have to make money and the messages need to be delivered, but we can't have messengers riding on the sidewalks and running through red lights all over the finan cial district."

According to Beene, irresponsible messengers pose a threat not only to motorists and pedestrians, but to themselves. The only way to insure safety, he feels, is to force them into compliance with the vehicle code. And the Unit’s Hondas meet the messengers on their own turf.

“Messengers are almost impossible to police by foot or patrol car,” Beene says. “They can maneuver so effortlessly and efficiently that the only way we can control them is with the Hondas. Unlike other methods of enforcement, the Hondas can follow the messengers up sidewalks, down stairs and even into BART (subway) stations. The 250s are definitely an important part of our tactical division. I don't know how any urban powhat it takes to make a good San Francisco messenger. The job requires a significant commitment of time and energy, and a willingness to endure high-speed chases, foul weather and unexpected breakdowns in the middle of nowhere. It all goes with the territory.

But to the dedicated motorcycle messenger, the rewards are just compensation. “There’s really no job like this in the world,” claims one veteran of the delivery wars. “People describe us as outlaws and madmen, but there’s only one way I can sum up the experience of being a motorcycle messenger: total freedom.” £3 lice department could keep messengers in line without them.”

Faced with that kind of effective law enforcement, San Francisco's motorcycle messengers seem destined to pay dearly for over-aggressive riding tactics. More and more of them have come to know all of the Honda Unit’s patrolmen on sight. Some even refer to officers of the Unit as “marines on motorcycles.” But as long as they are faced with almost impossible deadlines, these two-wheel couriers will resort to whatever means necessary to get the message delivered on time.

Obviously, then, not everyone has

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Editorial

EditorialDiscovering the Truth In Turn One

September 1986 By Paul Dean -

At Large

At LargeLife Under A Liter

September 1986 By Steven L. Thompson -

Letters

LettersLetters

September 1986 -

Roundup

RoundupTop-Secret Struggles

September 1986 -

Roundup

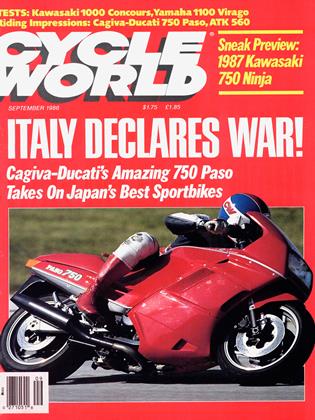

RoundupItaly First, And Then the World

September 1986 By Alan Cathcart -

Features

FeaturesMassimo Tamburini On Pasos And Paganini

September 1986 By Steve Anderson