19-DELTA FOR A DAY

A 24-hour tour of duty as an Army motorcyclist

SEAN GALLAGHER

THE 9TH CAVALRY RIDES AGAIN. AND HOW! History books provide only a glimpse of the illustrious past of the 9th Calvary. Organized shortly after the Civil War, this unit consisted entirely of black enlisted men led by white officers. The prevailing prejudices of the day overshadowed their extensive accomplishments during the Indian Wars of the late 1800s; but from their adversaries, they earned the nickname “Buffalo Soldiers," in tribute primarily to their tight, curly hair, and secondarily to their tenacious fighting spirit. Harrassed by both civilian and Army authorities, they were equipped with old and damaged equipment, and assigned to the most miserable quarters and dirtiest jobs on the Western frontier. Yet, despite the adversity, they fought fiercely in the face of the most daunting odds.

Today, paved interstates rather than dusty trails crisscross the American West, and the pony and mounted horseman are things of the past. But the 9th Cavalry prevails. With the squadron’s unit insignia—an Indian in breech cloth mounted on a galloping pony—as a reminder of the past, the 9th Cavalry is prepared as always to lead the troops into battle.

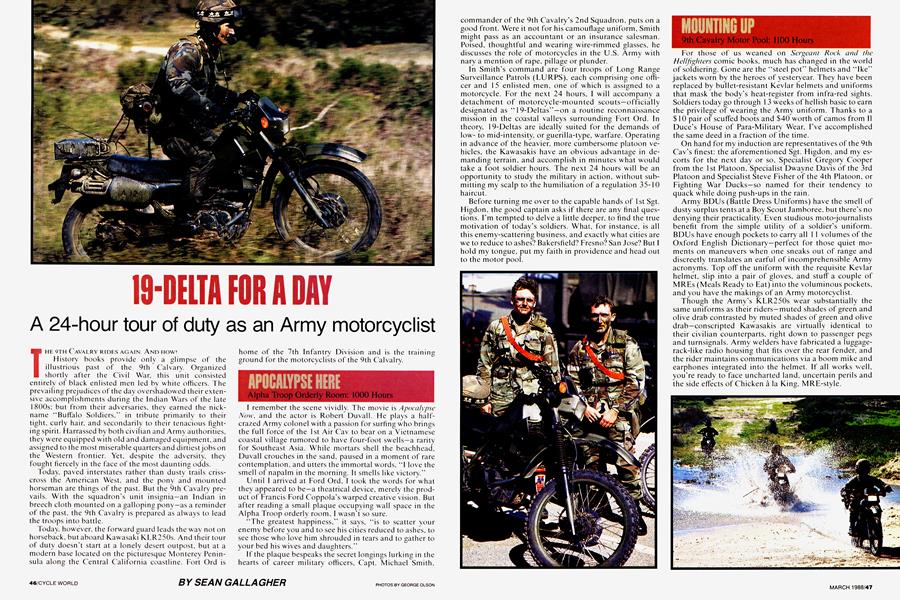

Today, however, the forward guard leads the way not on horseback, but aboard Kawasaki KLR250s. And their tour of duty doesn't start at a lonely desert outpost, but at a modern base located on the picturesque Monterey Peninsula along the Central California coastline. Fort Ord is home of the 7th Infantry Division and is the training ground for the motorcyclists of the 9th Calvalry.

APOCALYPSE HERE

Alpha Troop Orderly Room: 1000 Hours

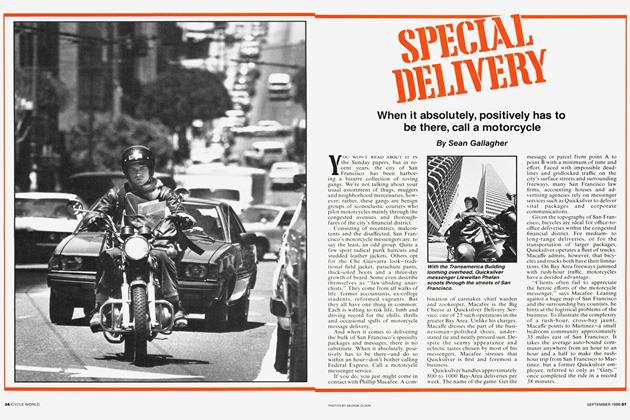

I remember the scene vividly. The movie is Apocalypse AW, and the actor is Robert Duvall. He plays a halfcrazed Army colonel with a passion for surfing who brings the full force of the 1st Air Cav to bear on a Vietnamese coastal village rumored to have four-foot swells—a rarity for Southeast Asia. While mortars shell the beachhead, Duvall crouches in the sand, paused in a moment of rare contemplation, and utters the immortal words, “I love the smell of napalm in the morning. It smells like victory."

Until I arrived at Ford Ord, I took the words for what they appeared to be—a theatrical device, merely the product of Francis Ford Coppola's warped creative vision. But after reading a small plaque occupying wall space in the Alpha Troop orderly room, I wasn’t so sure.

“The greatest happiness," it says, “is to scatter your enemy before you and to see his cities reduced to ashes, to see those who love him shrouded in tears and to gather to your bed his wives and daughters."

If the plaque bespeaks the secret longings lurking in the hearts of career military officers, Capt. Michael Smith, commander of the 9th Cavalry’s 2nd Squadron, puts on a good front. Were it not for his camouflage uniform. Smith might pass as an accountant or an insurance salesman. Poised, thoughtful and wearing wire-rimmed glasses, he discusses the role of motorcycles in the U.S. Army with nary a mention of rape, pillage or plunder.

In Smith’s command are four troops of Long Range Surveillance Patrols (LURPS), each comprising one officer and 15 enlisted men, one of which is assigned to a motorcycle. For the next 24 hours, I will accompany a detachment of motorcycle-mounted scouts—officially designated as “ 1 9-Deltas”—on a routine reconnaissance mission in the coastal valleys surrounding Fort Ord. In theory, 19-Deltas are ideally suited for the demands of lowto mid-intensity, or guerilla-type, warfare. Operating in advance of the heavier, more cumbersome platoon vehicles, the Kawasakis have an obvious advantage in demanding terrain, and accomplish in minutes what would take a foot soldier hours. The next 24 hours will be an opportunity to study the military in action, without submitting my scalp to the humiliation of a regulation 35-10 haircut.

Before turning me over to the capable hands of 1st Sgt. Higdon, the good captain asks if there are any final questions. I’m tempted to delve a little deeper, to find the true motivation of today’s soldiers. What, for instance, is all this enemy-scattering business, and exactly what cities are we to reduce to ashes? Bakersfield? Fresno? San Jose? But I hold my tongue, put my faith in providence and head out to the motor pool.

MOUNTING UPZ

9th Cavalry Motor Pool: 1100 Hours

For those of us weaned on Sergeant Rock and the Hellfighters comic books, much has changed in the world of soldiering. Gone are the “steel pot” helmets and “Ike” jackets worn by the heroes of yesteryear. They have been replaced by bullet-resistant Kevlar helmets and uniforms that mask the body’s heat-register from infra-red sights. Soldiers today go through 13 weeks of hellish basic to earn the privilege of wearing the Army uniform. Thanks to a $ 10 pair of scuffed boots and $40 worth of camos from II Duce's House of Para-Military Wear, I’ve accomplished the same deed in a fraction of the time.

On hand for my induction are representatives of the 9th Cav’s finest: the aforementioned Sgt. Higdon, and my escorts for the next day or so. Specialist Gregory Cooper from the 1st Platoon, Specialist Dwayne Davis of the 3rd Platoon and Specialist Steve Fisher of the 4th Platoon, or Fighting War Ducks—so named for their tendency to quack while doing push-ups in the rain.

Army BDUs (Battle Dress Uniforms) have the smell of dusty surplus tents at a Boy Scout Jamboree, but there’s no denying their practicality. Even studious moto-journalists benefit from the simple utility of a soldier’s uniform. BDUs have enough pockets to carry all 1 1 volumes of the Oxford English Dictionary—perfect for those quiet moments on maneuvers when one sneaks out of range and discreetly translates an earful of incomprehensible Army acronyms. Top off the uniform with the requisite Kevlar helmet, slip into a pair of gloves, and stuff a couple of MREs (Meals Ready to Eat) into the voluminous pockets, and you have the makings of an Army motorcyclist.

Though the Army's KLR250s wear substantially the same uniforms as their riders—muted shades of green and olive drab contrasted by muted shades of green and olive drab—conscripted Kawasakis are virtually identical to their civilian counterparts, right down to passenger pegs and turnsignals. Army welders have fabricated a luggagerack-like radio housing that fits over the rear fender, and the rider maintains communications via a boom mike and earphones integrated into the helmet. If all works well, you’re ready to face uncharted land, uncertain perils and the side effects of Chicken à la King. MRE-style.

SNEAK AND PEEK

Lamb Chop Hill: 1300 Hours

The military goes to great expense and through an arduous selection process before turning an Army motorcycle over to a dog-tagged berm-crusher. Applicants first attend a mandatory training course patterned after those offered by the Motorcycle Safety Foundation before participating in a demanding, three-day field test of willpower and stamina. Then, and only then, do they join the troop.

Alpha Troop en masse is a formidable display of armaments. The arsenal consists of five High Mobility MultiPurpose Wheeled Vehicles (HUM-Vs) and one KLR250. Slated as replacements for the venerable Jeep. HUM-Vs tower over their humble predecessors and come equipped with either Tube-Launched Optically Sighted WireGuided (TOW) missiles, .50-caliber machine guns, or command communications equipment. Normally, only one KLR is assigned per troop, but for my benefit. Specialists Fisher, Davis and Cooper will serve as escorts.

With the final touches of camouflage black-out applied, our unlikely patrol departs. Our mission, near as I can tell, is to scout the surrounding terrain to verify levels of enemy troop concentrations and find concealed recon routes for the HUM-Vs. Since KLR-mounted 19-Deltas carry only sidearms, we're ill-prepared to do much of anything else but sneak, peak and report. It sounds more like a child's game than a military tactic.

On the trail, we reel in several miles of effortless, hardpacked fireroad before angling off onto a rain-gouged side trail three inches deep in a fine. Central California sand. For my escorts with a home-court advantage, the transition is smooth and effortless. They downshift, pivot and claw' through the sandw ash. leaving a blanket of dust and a blind journalist in their wake. My attempt to make the same transition has less than satisfactory results, and my subsequent effort to extricate myself from a prone Kawasaki meets with resistance from an uncooperative pant seam snagged on the accursed fuel petcock. Five minutes as a war correspondent and I'm already a casualty.

After I regain my dirt legs, we continue our mission. Who is moving troops and supplies into the tranquil, forested hills of the Central California Coast, we know not, but we are the eyes and ears of the commander and our duty is clear: Sneak, peak and report. After scaling ridge after ridge, after riding through murderous sandwashes and fording treacherous swamps, after twisting through narrow gorges and blasting wide-open along groomed fireroads, the only traces of enemy activity we encounter are an abandoned Chevy rusting in an open field and a herd of 37 (yes. I counted them) sheep oblivious to the seriousness of military maneuvers. As the impulse to call in an air-strike passes, we fire up and steer the KLRs homeward.

Mud-spaekled and trail-weary, we rejoin Alpha Troop, under the watchful gaze of Sgt. Tillinghast. “1 don't want to see them hurt." says the good sergeant of his twowheeled scouts. “But I don't mind seeing them get wet," he adds as he climbs back into the welcome warmth of a heated HUM-V.

SHOTS IN THE DARK

Night Recon: 2030 Hours

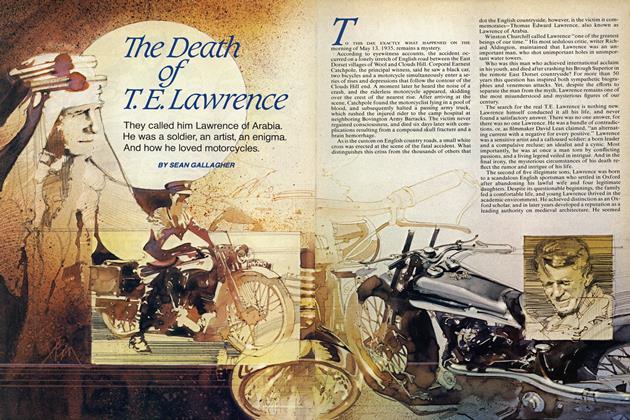

Specialist Cooper, 1st Sgt. Higdon and I slowly freeze like so many camouflage-flavored ice cream cones, while Cycle World photographer George Olson dances through the dark, armed with a battalion of whirring Nikons, a bevy of high-speed lenses and a red spotlight meant to simulate the view through a thermal sight.

Though the attempt lacks the realism of a war documentary. it does dramatize the role of the 19-Delta in Night Recon. and the importance of night-vision goggles. Alternately termed either Starlights or Passive Sighting Systerns, night-vision goggles amplify existing starlight and transform the bleakest moonless night into daylight. The amplification is so intense that a solitary figure traversing an open field less than 50 yards away is clearly visible, including even his shadow.

While passive sighting systems are an obvious advantage during night surveillance, they pose some interesting problems for the rider. Trying to ride while wearing nightvision goggles is like trying to maneuver with postal tubes glued to your eye sockets. Both peripheral vision and depth of field are extremely limited. And since the device only registers light in clearly discernable shades of green, shadows and pot-holes often tend to have the same characteristics, often leading to disastrous results.

But despite the bugs in the system, there is no shortage of eager volunteers willing to put the Army KLRs through their paces, with or without night-vision goggles. “Hell,” said one sergeant, “every E-4 and half the E-5s and 6s we have want to ride those damn motorcycles.” And, all things considered, it sure beats trudging through the slime with a 60-pound field pack.

TO RE-UP OR NOT TO RE-UP

The Following Day

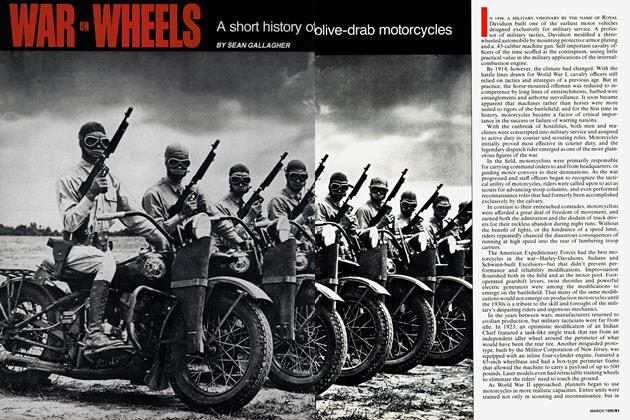

Motorcycles are nothing new to the U.S. Army. For years they’ve served in reconnaissance and combat roles, yet their value is often overlooked by the public at large, and ignored by the press and Hollywood.

Army recruiters, however, are having a field day. On the surface, it seems a good racket—four years on an Army motorcycle, collect a couple of grand in Army collegeeducation bucks, and maybe even make a radio commercial or two: “My pal Jesse and I were bored with our weekends . . ..”

But in active engagement, a motorcycle scout has an average life-expectancy of just 7 to 10 seconds—a detail they forget to mention down at the recruiting office when they’re busy dishing out 8-by-10 glossies of camouflage KLRs. Yesterday’s frolic in the rolling hills and pastures around Fort Ord was little more than fun and games, but in the Army, scenery has a way of changing. Tomorrow it might be Mindanao, or Angola, or Beirut, places where shadows and the rustle of underbrush have deadly consequences, where the players don’t register kills with Lazer Tag sensors, but with real bullets.

Specialist Fisher, though, deserves the credit for the most succinct assessment of the Army motorcyclist’s lot. After four years in the Army, he stands behind a desk in the Alpha Troop orderly room. Before him rests a sheaf of freshly typed re-enlistment papers. With his signature, Fisher will be obligated to spend four more years in the Army, guaranteed of only one thing—an additional 12 months at Fort Ord riding Army motorcycles. And as far as Fisher is concerned, that's not a bad trade.

“We all realize we’re expendable,” he says. “But at least if we get killed on a motorcycle, we'll get buried in a regular-sized casket. It’s a hell of a lot better than having your body parts scattered all over a mine field.”

Who can argue with logic like that? 0

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Departments

DepartmentsEditorial

March 1988 By Steve Anderson -

Departments

DepartmentsLeanings

March 1988 By Peter Egan -

Letters

LettersLetters

March 1988 By Hector Cademartori -

Roundup

RoundupThe Perfect Motorcycle

March 1988 By Camron E. Bussard -

Roundup

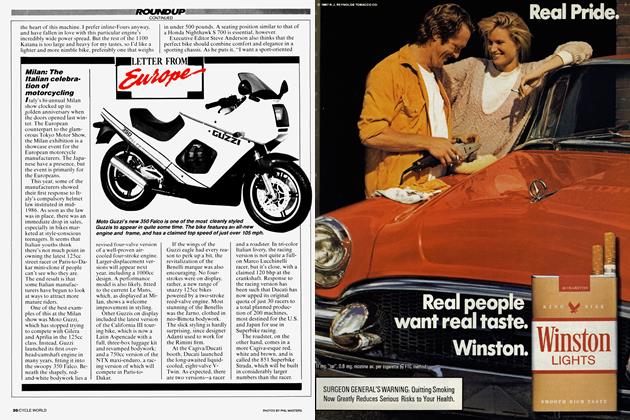

RoundupLetter From Europe

March 1988 By Alan Cathcart -

Roundup

RoundupDestinations

March 1988 By David Edwards