Subduing The Sahara

Short of food, fuel and water . . . but never sand.

Daniel Richard

NOBODY BELIEVED it when I told them. “You’re going to what?” they gasped. “Cross the Sahara Desert on a motorcycle? But it can’t be done, can it?” As though it could, I snapped my fingers and mumbled something about making pies. But could a motorcycle even make it across the Sahara?

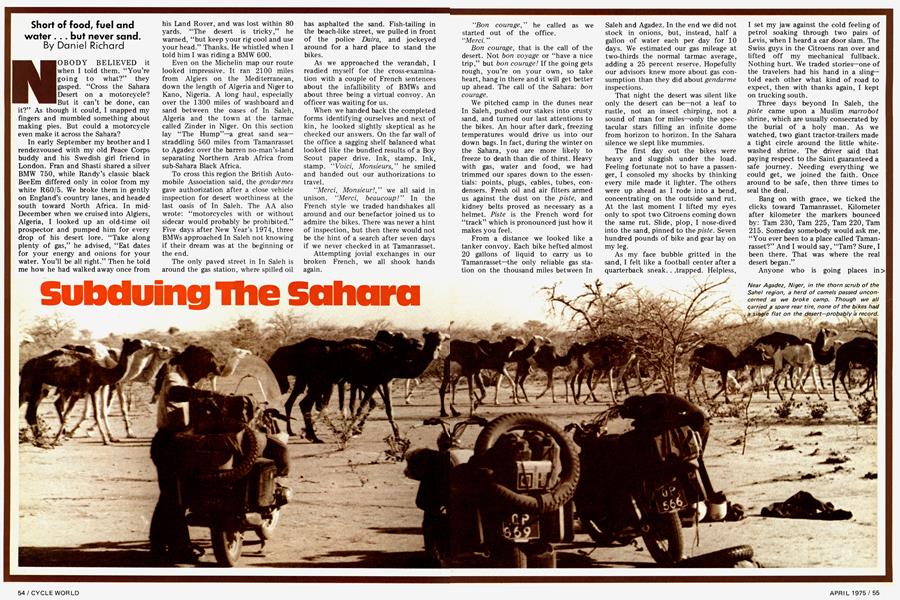

In early September my brother and I rendezvoused with my old Peace Corps buddy and his Swedish girl friend in London. Fran and Shasti shared a silver BMW 750, while Randy’s classic black BeeEm differed only in color from my white R60/5. We broke them in gently on England’s country lanes, and headed south toward North Africa. In midDecember when we cruised into Algiers, Algeria, I looked up an old-time oil prospector and pumped him for every drop of his desert lore. “Take along plenty of gas,” he advised, “Eat dates for your energy and onions for your water. You’ll be all right.” Then he told me how he had walked away once from his Land Rover, and was lost within 80 yards. “The desert is tricky,” he warned, “but keep your rig cool and use your head.” Thanks. He whistled when I told him I was riding a BMW 600.

Even on the Michelin map our route looked impressive. It ran 2100 miles from Algiers on the Mediterranean, down the length of Algeria and Niger to Kano, Nigeria. A long haul, especially over the 1300 miles of washboard and sand between the oases of In Saleh, Algeria and the town at the tarmac called Zinder in Niger. On this section lay “The Hump”—a great sand seastraddling 560 miles from Tamanrasset to Agadez over the barren no-man’s-land separating Northern Arab Africa from sub-Sahara Black Africa.

To cross this region the British Automobile Association said, the gendarmes gave authorization after a close vehicle inspection for desert worthiness at the last oasis of In Saleh. The AA also wrote: “motorcycles with or without sidecar would probably be prohibited.” Five days after New Year’s 1974, three BMWs approached In Saleh not knowing if their dream was at the beginning or the end.

The only paved street in In Saleh is around the gas station, where spilled oil has asphalted the sand. Fish-tailing in the beach-like street, we pulled in front of the police Daira, and jockeyed around for a hard place to stand the bikes.

As we approached the verandah, I readied myself for the cross-examination with a couple of French sentences about the infallibility of BMWs and about three being a virtual convoy. An officer was waiting for us.

When we handed back the completed forms identifying ourselves and next of kin, he looked slightly skeptical as he checked our answers. On the far wall of the office a sagging shelf balanced what looked like the bundled results of a Boy Scout paper drive. Ink, stamp. Ink, stamp. “Voici, Monsieurs, ” he smiled and handed out our authorizations to travel.

“Merci, Monsieur!,” we all said in unison. “Merci, beaucoup!” In the French style we traded handshakes all around and our benefactor joined us to admire the bikes. There was never a hint of inspection, but then there would not be the hint of a search after seven days if we never checked in at Tamanrasset.

Attempting jovial exchanges in our broken French, we all shook hands again.

“Bon courage, ” he called as we started out of the office.

“Merci. ” Bon courage, that is the call of the desert. Not bon voyage or “have a nice trip,” but bon courage! If the going gets rough, you’re on your own, so take heart, hang in there and it will get better up ahead. The call of the Sahara: bon courage.

We pitched camp in the dunes near In Saleh, pushed our stakes into crusty sand, and turned our last attentions to the bikes. An hour after dark, freezing temperatures would drive us into our down bags. In fact, during the winter on the Sahara, you are more likely to freeze to death than die of thirst. Heavy with gas, water and food, we had trimmed our spares down to the essentials: points, plugs, cables, tubes, condensers. Fresh oil and air filters armed us against the dust on the piste, and kidney belts proved as necessary as a helmet. Piste is the French word for “track” which is pronounced just how it makes you feel.

From a distance we looked like a tanker convoy. Each bike hefted almost 20 gallons of liquid to carry us to Tamanrasset—the only reliable gas station on the thousand miles between In Saleh and Agadez. In the end we did not stock in onions, but, instead, half a gallon of water each per day for 10 days. We estimated our gas mileage at two-thirds the normal tarmac average, adding a 25 percent reserve. Hopefully our advisors knew more about gas consumption than they did about gendarme inspections.

That night the desert was silent like only the desert can be—not a leaf to rustle, not an insect chirping, not a sound of man for miles—only the spectacular stars filling an infinite dome from horizon to horizon. In the Sahara silence we slept like mummies.

The first day out the bikes were heavy and sluggish under the load. Feeling fortunate not to have a passenger, I consoled my shocks by thinking every mile made it lighter. The others were up ahead as I rode into a bend, concentrating on the outside sand rut. At the last moment I lifted my eyes only to spot two Citroens coming down the same rut. Slide, plop, I nose-dived into the sand, pinned to the piste. Seven hundred pounds of bike and gear lay on my leg.

As my face bubble gritted in the sand, I felt like a football center after a quarterback sneak. . .trapped. Helpless, I set my jaw against the cold feeling of petrol soaking through two pairs of Levis, when I heard a car door slam. The Swiss guys in the Citroens ran over and lifted off my mechanical fullback. Nothing hurt. We traded stories—one of the travelers had his hand in a slingtold each other what kind of road to expect, then with thanks again, I kept on trucking south.

Three days beyond In Saleh, the piste came upon a Muslim marrobot shrine, which are usually consecrated by the burial of a holy man. As we watched, two giant tractor-trailers made a tight circle around the little whitewashed shrine. The driver said that paying respect to the Saint guaranteed a safe journey. Needing everything we could get, we joined the faith. Once around to be safe, then three times to seal the deal.

Bang on with grace, we ticked the clicks toward Tamanrasset. Kilometer after kilometer the markers bounced by: Tam 230, Tam 225, Tam 220, Tam 215. Someday somebody would ask me, “You ever been to a place called Tamanrasset?” And I would say, “Tam? Sure, I been there. That was where the real desert began.”

Anyone who is going places in Tamanrasset meets at the gas pumps. The first afternoon there we buttonholed truckers and travelers hot off the southern piste for their reports. Sand, sand, lots of sand was all we heard. No one encouraged us to attempt “The Hump.” That night Fran and Shasti decided not to risk two on a bike and arranged for Shasti to ride to Agadez with five Canadians we had met at the marrobot. Tomorrow—after customs and immigration—the desert grapevine would know us as “the three Americans on motorcycles” like a newspaper headline.

Next morning, 50 miles south of Tam, the Hoggar Mountains fell behind us, and we throttled onto a great sand sea as flat as the ocean and giving the same illusion to tempt a survivor to “go have a look around.” The sun climbed on our left, and with it came the wind.

The heat rose and the sand-ladened sirocco wind quickly turned into a stinging blast obliterating any trace of the track. Deciding it was foolish to guess, we parked the machines’ tails into the wind and stopped the pipes with rags. There was nothing to do but wait out the storm. We stood around like bulky astronauts, wearing our goggles and helmets and gloves, and grew to appreciate the usefulness of the Tuerreg’s flowing turban called a cheche. By noon the sand storm let up enough to expose the track.

Two hours later we were approaching the border where ragged children began to race across the flats trying to make our paths meet. One teenaged boy made it. After we gawked at each other, admiring his sword and my bike, he made a gesture like tossing a handful of M&Ms into his mouth.

“Sorry, no candy, but have a cigarette.”

He accepted them in cupped hands, put two away for later, then expertly emptied the tobacco of the third into his palm and popped it all into his mouth. Why waste a precious match when you can chew?

Dusk stopped us that night after crossing the Algerian border at In Guezzam. Tomorrow would mean Assamaka, and I remembered the Dutchman’s words in Tamanrasset: “Transport lorries stuck in the sand there, much sand.”

He was right. From a distance, shimmering in the heat haze, Assamaka was two palm trees and a pueblo of low buildings in the middle of nowhere. There was no road, only a line of posts leading to the border station. Struggling through the sand mile after mile in first gear made us recheck our mileage while we waited for our passports at the oasis. Bad news. Besides using more gas feathering the clutch in low gear, evaporation sucked our supply, and the average mileage fell below our estimate, eating into our reserve. Luckily, a few gallons from a Canadian couple in a zebra painted camper did not jeopardize their supply. At one ‘o’clock, when normal nomads napped, we hit the piste. It was our biggest mistake.

A quarter of a mile out of sight of Assamaka, we discovered what the Tuerregs call feche feche: soft, churned, bottomless sand. We were once told the desert Tuerregs have as many names for sand conditions as Eskimos have for snow. If you kept speed, your front wheel soon jackknifed in the mounds. If you slowed, your rear wheel sank into the sand like a hot ball bearing into Crisco. We tried everything. After each try we could smell our clutch plates. Our tires smoked in the sand. And the sun made metal too hot to touch. The desert had come to get us.

In one horrendous effort, the three of us galloped and cussed one bike through a 30-yard patch.

“Hey, man, our clutches won’t take much more of this,” Fran said.

“Christ, it’s hot,” Randy unzipped his Barber jacket. “They said it was 121 at the oasis.”

We passed around the squeeze bottle of water; just as refreshing and the spray used far less water. Without speaking we trudged back to bring up the other machines. My brother picked a good path and pulled away from us.

“Ride it, Ran!”

“Goose it, baby! Goose it!”

Then the bike faltered, slowed and settled down like a mother hen on a nest. He stepped off and the BMW just stood there up to its pipes in sand. The glare of the desert made us squint.

“Damn, thought I had it.” Ten feet farther was the end of the patch of feche feche. Frustration turned on us.

“What if it’s like this all the way?”

“What if it isn’t?” snapped Fran.

“You can’t go far without a clutch,” I countered. “And in this heat we’ll lose it right quick.”

“Yeah, well maybe you want to stand here until the Boy Scouts come to save you.”

“Gent bent. What I said was, it’s the hottest time of the day. Let’s stay cool, take a break and try later when we don’t have to fight this heat too.”

“Hell, man, if we quit each time it gets tough, we’ll never make it. What do you say, Ran?”

“It may get better up there,” he nodded toward the next marker post. “I think we should give it one more go.”

“Okay, one more go,” I conceded. I wished Fran would burn out his clutch just to prove he was not always right.

Fran went first as usual. He picked up momentum, steadied his line in a tire track, plowing through the soft sand. As he sank, we ran behind him lifting his back end to equalize the drag of the sand. Sand sprayed from his wheel like a water skier’s fantail. Unexpectedly, the desert hardened and he galloped away from us leaving a trail like a waddling turtle. Randy was next.

Taking an education from the first track, my brother rode his A African Queen” hard and strong up next to Fran. Bogie would have been proud. Following suit, I shot on past and we all began to cruise again over the gravel flats. The breeze cooled our nerves as we put the sands of Assamaka behind us.

It had been 16 days since we left Algiers. Riding day after day due south, 1500 miles into the Sahara. Few vehicles traveled “The Hump” and only the occasional camel greeted us between the markers. Southward, always south. Suddenly we all pulled up short. We were lost.

“Did you see the last post?”

“No, I was following you. Last one I saw was before all those camels. Can you spot the next one?”

“I thought that was a marker,” Fran said pointing at a scraggy tree. “Everything wiggles in these heat mirages.” Randy looked up from the map, “According to this, we go straight. I wonder if those camels back there were at a well. Abangarit should be around here somewhere.”

Then for the first time we noticed we were surrounded by hundreds of thousands of camel footprints.

“That Englishman’s instructions say we should turn a sharp left at the village of Abangarit near a ruined house. But he’s been wrong before.” After weeks of riding south it seemed strange to me to suddenly change direction.

“Do you suppose that well was Abangarit?” Randy remembered, “There was a pile of bricks there.”

The only thing to do was follow our tracks back until we recognized something. Turning around, the whole world changed. Tire tracks went in all directions muddled with camel prints. What should have been an easy task became a nightmare in a hard patch of gravel where we lost our treads. We doubled back and spread out, only to confuse ourselves with our own tracks.

(Continued on page 90)

Continued from page 57

“What now?”

“We must stick with the bulk of the tracks and find the well again,” I reasoned.

“Which dozen do you prefer?”

“North. Follow the compass north.”

The camel tracks gave us a clue and eventually we sighted the ruined building. Scanning the horizon, something caught Fran’s eye to the East. It was not a post. It looked more like a tombstone. Probably some tourist’s grave, I imagined. We rode toward it.

The tire tracks became more numerous as we came up to a cement marker shaped like the hundred pound weight of a circus strongman. The highway department had switched markers on us at the only turn in 1500 miles. We had found the track: east by southeast.

Later in camp, relief gave the vegetable beef soup an extra flavor as we pretended not to notice having broken into our reserve survival rations. The last of our gas went into half empty tanks, and only the sulfurous Assamaka water was left to drink. The track was a road again and somewhere at the end was Agadez. How far was the question.

In the morning we took bets on the mileage to Agadez. Nobody put their money on less than a hundred miles. Surrounding us was the Sahel where the drought had strangled the nomads’ cattle, driving the survivors to the relief centers. The thorn trees had taken over. The corrugations and sand holes soon forced us off the road, dancing between the bushes where a Rover could not go.

Coming up a rise, we saw it. There on a hill was the red and white striped water tower of Agadez. We did it! We crossed the Sahara! Riding three abreast we roared into the sleepy town all smiles and running on reserve. There on the main street was Shasti.

“Where have you been?” she asked. “We expected you yesterday.”

“Wanted to enjoy the scenery,” winked Fran.

There was more desert to the south, but we were veterans. It could not be worse than Assamaka.

Two days later at home in America, our parents drank a relieved toast as they read the telegram: SAHARA CONQUERED HAPPY NEW YEAR YOUR SONS.