Adventure Seeker

FEATURES

Searching for the meaning of adventure on a 16-day, $10,000 tour through the wilds of Africa with Long Way Round’er Charley Boorman as our guide

GARY INMAN

THE E-MAIL ARRIVES FROM A 'ROUND-THE-WORLD motorcycle adventurer. "Have a good holiday," it says, “but don’t let anyone call it an adventure.”

That line is loaded with so many toxic ingredients I can almost smell it. It’s written from an experienced standpoint, sure, but laced with an air of superiority and dash of arrogance. It lands the day before I fly to Cape Town to join a tour group riding more than 3000 miles in 16 days. It’s a trip advertised by its provider, Moto Aventures, as “An adventure of a lifetime.” The majority of the riding is on dirt and gravel tracks, from the southern coast of South Africa, through Namibia and into Zambia.

That e-mail knocks off a scab I’ve been picking since I accepted the invitation. As a lover of bikes, of new experiences and of going my own way whenever possible, I wondered if this “adventure” would become too diluted by having an itinerary, guides and backup. Or worse, would I be forced to live with disparate riders I have no fondness of and little in common with for over two weeks? There is only one way to find out.

What you get for your money

The ride is organized by Moto Aventures’ Su Downham and John Griffiths, now in their 15th year of providing off-road motorcycle trips. The 2012 Charley Boorman tour (August 23 to September 7, 2012) will cost €7600 ($10,361 ) for riders, €3400 ($4635) for pillions and €4400 ($5998) for partners who travel in the backup car. This will be much the same trip as mine but with the chance to extend the ride from Victoria Falls into Zimbabwe and Malawi, through Tanzania and finishing in Kenya.

On my tour, all the overnight accommodations were covered, including the night before the start in Cape Town and the last night in Victoria Falls. Every breakfast and evening meal was included, as was bike rental and insurance (not personal insurance)—though there is a hefty charge for any bike damage. Attendance at the BMW Off-Road Course in Wales is also part of the price but can be deducted if you can’t attend. Riders do have to buy flights to and from South Africa, along with gas for bikes, their own lunches and drinks, border-crossing costs and the odd extra excursion.

For more prices and details, log onto www.motoaventures-touring.com.

I meet the group at a Cape Town hotel. I recognize a handful of the 22 riders (plus two pillions) from the BMW Off-Road Skills course that was part of the substantial €7450 (about $10,000) price. While everyone in the group has traveled extensively, some, amazingly, have little motorcycle experience.

For most of the participants, part of the attraction of the tour is that it’s being led by Charley Boorman of Long Way Round and Long Way Down fame. This isn’t an endorsement deal; Boorman will ride every mile of the route, then pause for three days and lead another group from Victoria Falls back to Cape Town on an additional 16-day jaunt.

The next morning, we leave at 9, programmed Garmins showing us the route. For now, it’s all tarmac and mindbogglingly beautiful. We follow the coast and climb the 114 curves of the six-mile Chapman’s Peak Drive. “Do not feed the baboons” signs add a taste of the exotic. The Cape of Good Hope sounds impossibly romantic but doesn’t disappoint. Whitecaps smash into the cliffs. Whales breach the surface of the deep blue below. It’s the most beautiful day’s riding I’ve ever had.

The end of the day gives the first taste of gravel, and my provided BMW R1200GS and I lap it up. Life, it seems, can’t get any better. Then I arrive at the Franshoeck Hotel on the outskirts of the chichi town of the same name. “Glass of port?” asks the pretty welcoming committee. Don’t mind if I do.

Day two starts gray and delivers the only rain of the journey. In the afternoon, the riders are given a choice of a hard or easy route. I take the hard. It’s stunning and technically challenging, with steep descents and water crossings, but only one 100-meter section of fine, deep sand causes any of the riders a problem. The “hard” group is a trio of Americans, three Australians, plus me, Charley, Billy and a fearless Scots couple, two-up. The riders get strung out as some stop for photos, and the clump I congeal with pauses for tea and scones in a two-goat town. After more twisting single-track, we leave the offroad section. The day’s route relegates yesterday’s into the second-best day of riding I’ve ever had.

With less than 20 miles remaining to the hotel, the route turns into a twisting downhill race. As Charley and I slow at the outskirts of town and give each other a thumbs up, smiles all over our faces, I look over my shoulder for too long, stick a wheel on the dirt and I’m down at 40 mph. I don’t claim to be the fastest rider, but I pride myself for not having crashed a bike on tarmac for a decade and close to 100,000 miles.

I’m devastated. It’s only day two, I’m supposed to be the pro rider, and my BMW is upside-down in someone’s garden. Billy and Charley calm me down, delivering soothing platitudes. I’m expecting a fog of disapproval, but

. instead, Billy gives me the keys to his GS Adventure and tells me to go to the hotel.

The bike is history, but Tm okay. I start thinking how I can cover the $3000 excess damage fee and wonder if I’m going to enjoy the rest of the trip. I have a full two weeks to go. It’s going to drag if I don’t get out of this dark funk.

The next morning, a G650GS is awaiting me. That’s one massive benefit of being part of an organized group like this. I’ll ride this replacement for a single day until a bigger bike arrives.

Within a few miles of the off-road section of day three, we find Nabeel from Kuwait sitting on the grassbank.

He hit a deep washout and broke the borrowed R1200GS’s swingarm in two. No one has ever seen that happen before. Though new to biking, Nabeel is smiling.

So am I. The 650, which at first appeared a little feminine for my ego, is behaving like a trooper, and I’m already back in the groove, riding off-road with 85 mph on the clock and mirrors full of dust clouds. I’ll run my accident over in my head every day and night for the rest of the trip, but I’m enjoying the tour again.

That night, the last before we cross the border into Namibia, is spent in a kitsch hotel in Springbok. Riders clog the courtyard for some drinking and bonding, everyone still wearing the bottom half of their dusty riding gear and sweat-stained T-shirts. There are some strong characters, alpha males and oddballs. It’s already clear not everyone will see eye-to-eye.

The next morning, I am presented with an F800GS, a major upgrade from the 650. We then enter Namibia and continue through an endless landscape that seems as barren as the moon. Stunning, long-dead volcanic scenery frames the dirt road. Then, as the final left turn of the day approaches, an immense vineyard appears. It’s the site of the evening’s lodge on the banks of the Orange River. Later, we’re ferried in the back of pickups along a canyon bottom, and at the end, lit by flaming torches, is our open-air dining room for the night. It’s fairy-tale stuff. I eat too many lamb chops under the clearest smudge of Milky Way I’m ever likely to see.

For the next three stages, every night’s accommodation outdoes the last. 1 ride dusty tracks for six or seven hours, pausing for a drink, fuel and photos.

At one point, I park on a wide gravel track with four gemsbok oryx to my right. They keep still until I stare at them, then scarper. When I look back the way I came, eight ostrich cross the road. Tomorrow, I’ll experience the joy of my first sighting of wild elephant dung, rivaled only by the sight of a wild elephant disappearing into the trees. A day after that, Scottish Rob and Seattle Jimmy point out a giraffe to me. While 1 grab my camera, another five appear.

“I saw another huge deer-like thing, clay brown. Do you know what it is?” I ask Rob.

“No, but if 1 could taste it, I’d have a better idea,” he replies deadpan.

A challenging, nearly 200-mile offroad day’s riding leads through the Namib-Naukluft Park to Swakopmund and the tour’s halfway point. The landscape changes from flat and completely featureless sand to bizarre, interlocked green hillocks. The dust is terrible here, and you need good visibility. Taking eyes off the track for more than a couple of seconds guarantees a big moment as the front wheel finds a pothole, rut or ridge of gravel to put the bike into a disconcerting weave. After riding a short section of the Skeleton Coast, we head inland. Scenery varies from coastal to flat, featureless desert to Arizona plateau. Another perfect lodge with a clifftop restaurant awaits us.

The next day sees the most serious crash of the trip. Tim from New Jersey loses concentration on an off-camber right and hits a tough little tree. He’s knocked out and dazed when he comes to. Without fuss, he’s taken to a hospital where he stays overnight, accompanied by Su from Moto Aventures. The way the accident is dealt with sums up the professionalism of the organization. Nothing is more than a blip.

Whenever possible, the trip’s entire route avoids blacktop, and reading everchanging dirt surfaces is the element that’s giving me the most satisfaction.

A slight difference in color means a massive change in surface. Pale means smooth and hard-packed. Or soft and dangerous. It’s hard to explain, but it becomes instinctive. Tarmac, the surface I’ve spent all my life riding, suddenly seems tedious.

And while there might be support, it doesn’t make the sights any less beautiful or the roads any easier to ride. What’s wrong with having someone to pick and patch you up? And I really don’t want to change inner tubes in 98-degree heat. John, a stoic Brit, fixes puncture after puncture and services bikes every night. Before the end of the trip, a few of the group are already planning another Moto Aventures tour.

I keep thinking about that e-mail and my belief that the idea of motorcycle adventuring has become too earnest.

It seems all about one-upmanship. Look, you’re not Marco Polo or Neil Armstrong. I ride most of the days on my own and spend the night with new, good-time friends eating five-course meals and drinking tall drinks in incredible surroundings. Mark from Switzerland summed it up perfectly:

“I want hard days and clean beds.” Zambia’s border signals the last 70 miles of the trip. It’s a proper Central African experience with body odor you could chew and an insurance office made out of a rotten caravan. We pay our taxes and then ride to the hotel, a spit from Victoria Falls. Giraffes, monkeys, crocodiles and zebras walk in and out of the hotel’s open grounds. Many of the group’s bikes have arrived unscathed, while some people will have to pay for scrapes or worse.

It won’t be until I get back to work the following week that I realize how relaxed I was on the trip. There are a few long rides, but sometimes we were only in the saddle for five hours—less than that for the hammer-and-tongs frontrunners. The package is expensive, but the riders—who ranged from airport ground crew to bankers for the oil industry—all thought it offered good value. Everyone’s expectations were exceeded when it came to experiences and accommodation.

By now, the bruise on my lower back looks like a monstrous purple butterfly emerging from my butt crack. In my wake is a dead GS, 2500 miles with my ass hanging out of my trousers, some regret and a written-off helmet. But above it all, a ton of brilliant memories.

Experienced off-roaders thought it was a holiday, but the less-experienced were certain it was an adventure, perhaps the biggest they had ever seen in their lives. Some believe a trip with backup can never be an adventure, but my trousers would disagree. A solo rider could cover the route without backup or incident, staying at campgrounds, and most would consider it an adventure, but the ingredients would barely differ. This trip had a soft edge and gave a mouthful of wilderness to those unable, or unwilling, to take three to six months off to explore southern Africa. So what if it had a pre-planned itinerary? Thanks to the reconnaissance, the route was more circuitous and varied than many independents would search out in the same areas.

Ultimately, one person’s adventure is another’s meat and two veg. The trip was eventful, potentially dangerous, unforgettable and fun. That’s all I ever want my bike trips to be. And adventure is such an overused word now, anyway...

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

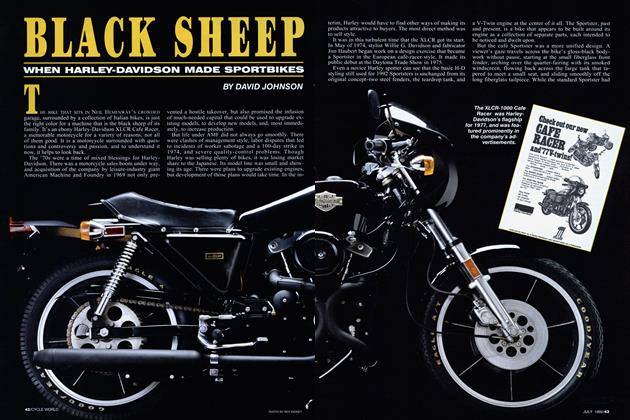

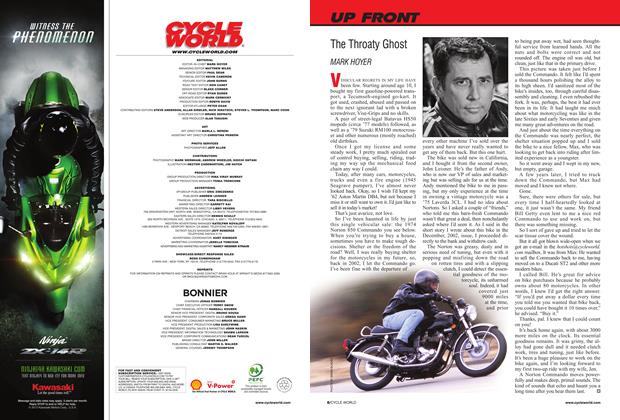

Up Front

Up FrontThe Throaty Ghost

FEBRUARY 2012 By Mark Hoyer -

Roundup

RoundupWhat's the Two-Wheel World Coming To Anyway?

FEBRUARY 2012 By John Burns -

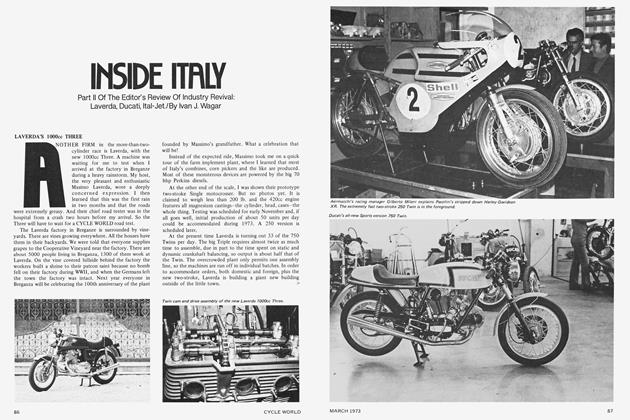

25 Years Ago February 1987

FEBRUARY 2012 By John Burns -

Roundup

Roundup2012 Zeros

FEBRUARY 2012 By Steve Anderson -

Roundup

RoundupDaineses D-Air Street

FEBRUARY 2012 By John Burns -

Roundup

RoundupMilestones Along the Way

FEBRUARY 2012 By Paul Dean