INSIDE ITALY

Part II Of The Editor's Review Of Industry Revival: Laverda, Ducati, Ital-Jet.

Ivan J. Wagar

LAVERDA'S 1000cc THREE

ANOTHER FIRM in the more-than-two-cylinder race is Laverda, with the new 1000cc Three. A machine was waiting for me to test when I arrived at the factory in Breganze during a heavy rainstorm. My host, the very pleasant and enthusiastic Masimo Laverda, wore a deeply concerned expression. I then learned that this was the first rain in two months and that the roads were extremely greasy. And their chief road tester was in the hospital from a crash two hours before my arrival. So the Three will have to wait for a CYCLE WORLD road test.

The Laverda factory in Breganze is surrounded by vine yards. There are vines growing everywhere. All the houses have them in their backyards. We were told that everyone supplies grapes to the Cooperative Vineyard near the factory. There are about 5000 people living in Breganza, 1300 of them work at Laverda. On the vine covered hillside behind the factory the workers built a shrine to their patron saint because no bomb fell on their factory during WWII, and when the Germans left the town the factory was intact. Next year everyone in Breganza will be celebrating the 100th anniversary of the plant founded by Massimo’s grandfather. What a celebration that will be!

Instead of the expected ride, Massimo took me on a quick tour of the farm implement plant, where I learned that most of Italy’s combines, corn pickers and the like are produced. Most of these monsterous devices are powered by the big 70 bhp Perkins diesels.

At the other end of the scale, I was shown their prototype two-stroke Single motocrosser. But no photos yet. It is claimed to weigh less than 200 lb. and the 420cc engine features all magnesium castings—the cylinder, head, cases—the whole thing. Testing was scheduled for early November and, if all goes well, initial production of about 50 units per day could be accommodated during 1973. A 250 version is scheduled later.

At the present time Laverda is turning out 33 of the 750 Twins per day. The big Triple requires almost twice as much time to assemble, due in part to the time spent on static and dynamic crankshaft balancing, so output is about half that of the Twin. The overcrowded plant only permits one assembly line, so the machines are run off in individual batches. In order to accommodate orders, both domestic and foreign, plus the new two-stroke, Laverda is building a giant new building outside of the little town. >

EXPANSION AT DUCATI

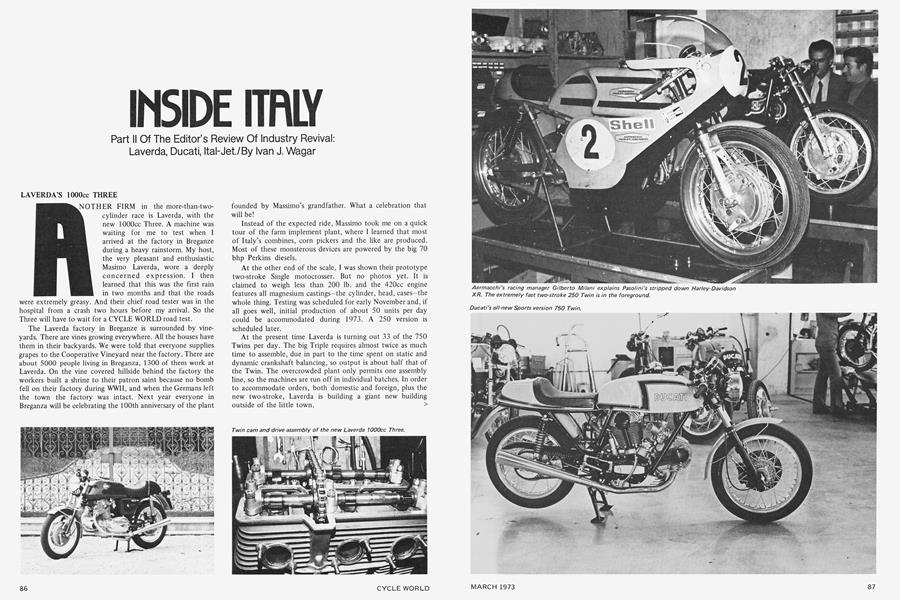

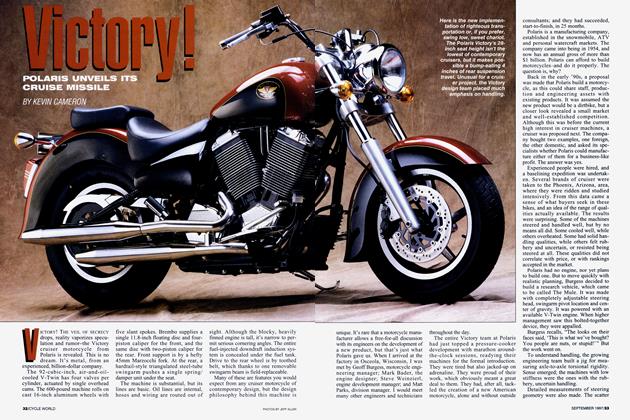

The expansion boom also has spread to Ducati. A beautiful, well-lit new plant in Bologna (famous for Italian cuisine) has just now started to get into full swing producing the 750 Twin and an exciting new Sports version of the machine previewed in CYCLE WORLD last September.

Ducati’s in-house genius, Ing. Taglioni, outlined the 750 Twin in 1969. The entire design concept was to provide for the use of as many already proven engine components as possible. And this is a practice that Taglioni favors; providing, of course, that a well-integrated final package will come out of the project. On the matter of the multi race for more cylinders he feels that Twins are sufficient, especially a V layout because of minimum width. But it is possible to design Twins of maybe 250, 375 and 475cc, and double up into Fours, if that is what the sales department wishes.

At the time of this writing, Ducati’s future race plans are not settled. The three-cylinder 350cc grand prix racer is temporarily shelved because of the tremendous expense and time requirements connected with that form of competition. Rumors of a Paul Smart/Ducati contract are more than rumors as far as the factory is concerned. They would like to get Paul and go F750 racing in a more serious way. Ducati’s only contract rider at this time is 39-year-old Bruno Spaggiari, who still puts in a good ride at times, but is a bit long in the tooth for a serious program.

Some consideration is being given to the sale of a limited number of Imola replicas. The machine would be identical to the one ridden by Smart when he gave the V Twin its first taste of F750 competition and won Europe’s biggest money race. Nearer at hand, however, is the Sport which now is in production. Featuring lighter pistons, rods, a little mort^^ compression, plus some other subtle changes, the Sport pulls two less teeth at the rear due to the higher power output, yet is smooth and tractable down low. The already excellent handling is further improved by the clip-on bars, which permit the rider’s wind drag to have less effect on handling. A solo seat, soft black cam box and case covers, and lack of air filtration differentiate the Sport from the normal 750.

ITAL-JET AND MINARELLI

No story about Italy would be complete without a look at the dynamic, warm, imaginative Leo Tartarini, founder and owner of Ital-Jet.

Half of the projects that Leo is involved in at any one time would drive most men crazy. But he thrives on work. Importer of Citroen cars, Italian importer for Yamaha, exporter of fine Italian wines, and he still has time to be one of the fastest growing small firms in Italy. Building Indian motorcycles for the U.S., frames for Ducati, among others, a line of mini-dune buggies and constructing a new plant were just a few of the^^ things underway during my visit. A former road racer for nine years, beginning in 1951, when he raced for five years for Benelli and the remainder for Ducati, Leo, like many former racers, * is relaxed and confident about himself and his programs.

Tartarini’s knowledge of the American market (he visits here frequently) and the Italian industry is most comprehensive. Taking time from his busy schedule he showed me through FB Minarelli, one of the world’s larger proprietary engine manufacturers and one of his suppliers. Minarelli builds about 150,000 engines a year and sells to most countries in the free world. Tartarini’s intimate knowledge of every phase of Minarelli’s operation was apparent within minutes; his sales figures and projections for this market were correct. Tartarini has it together, that’s about the best way to put it.

Although he does not have an engineering or art degree, Tartarini frequently is called upon by other manufacturers on a consulting basis. One firm told me they had hired Tartarini to find ways of cutting the cost of a particular model, bul^P found, in the end, the cost had gone up. They went on to explain that they didn’t mind because the product was better and their reputation would remain as a result. Tartarini has a fetish for quality.