Trials Notebook

A monthly course in the art of trials riding.

Instructors: Bob Nickelsen, Mike Obermeyer

This is our sign-off issue of the “Trials Notebook.” Foregoing the pomp and circumstance, it’s time you graduated these hallowed halls and struck out on your own. At this point we feel that we’ve shown you most of the basics, and quite a few advanced techniques. . .probably more than most of you have been able to completely absorb. But, as with the end of most projects, there are a lot of minor points we’d like to hit you with to finish up, some mechanical, some philosophical, and some regarding riding and practice. A lot of them will sound simple-minded and may be things that you’ve already figured out for yourselves. Others may be just what you needed to know.

1. Kill buttons should be mounted where they’ll work when they’re needed: like after you’ve dumped the bike upside down and the right handlebar is buried with the throttle stuck wide open. Therefore, mount them on the left-hand bar (preferably) or on the center of the bar. Angle the button so that it doesn’t hit your leg in a full-lock panic situation. The round, turning type (e.g. Honda) should have the rear-facing tab ground off so that you don’t turn it off by accident with your body. When your bike quits running and you’ve got no sparks, the kill button is the first thing to check; almost all of ’em malfunction sooner or later.

2. Rough running or “bad tune” usually shows up with time. If the bike isn’t spot-on, it can cost you points. Look for any or all of the following.

Electricals: timing off; point cam worn; points pitted and not making and breaking cleanly; water in the points (stick a hot engine in ice cold water and it has to make a vacuum); bum kill button; insulation worn through (look near steering head where kill button wire rubs during turns, and under flywheel where rubbing will instantly remove insulation); open circuits (check junction block under tank for loose screws, run continuity check on all wires with circuit tester or meter); condenser breakdown; open circuit in stator coil windings (check the last two by parts replacement). Trials bike wiring isn’t very complicated—there aren’t that many things that can go wrong.

Carburetion: If the electricals are all in order and it still doesn’t run right, it almost has to be in the air-fuel mix somewhere. This doesn’t always mean the carburetor, so try the following drill: take the carburetor off and apart, soak everything in alcohol or solvent, blow out all air passages with compressed air (check out a can of Dust-Off at your camera shop), check float level per manual specs, inspect float for leaks, note all jet, needle and slide sizes, then reassemble, replacing any worn parts. If in doubt, replace it, especially needle, needle seat and slide. Check carefully for air leaks between the carburetor and the cylinder; finding and fixing these may take a pressure test, plus lapping surfaces on flange-mounts, replacing hoses and clamps on spigots, plus liberal use of a temperature resistant sealer. Clean and re-oil your air cleaner.

If none of these things help, and especially if you have to jet differently from all your buddies with the same bikes, then you’ve probably got a leak in the crankcase-cylinder-head assembly. Does your primary case oil disappear? Is there oil on your points? These usually mean crankcase seal leaks. Have you retorqued your head bolts? If there’s blow-by there, the head may need to be lapped; try cleaning surfaces carefully and retorqueing first. Some bikes have been known to leak at the centerline junction between crankcase halves. Believe it or not, roughing up with sandpaper and a spot of good epoxy may cure this!

3. Accessories and replacements: Renthal bars are supei^when new! Radius clamps carefully and check for fatigue. Lane Leavitt lost the 1972 Trial de España to Sammy Miller because a pair of aging Renthals broke. You can bet he replaces them frequently now. Sprockets and chains must be watched and replaced as needed, as must wheel bearings. You can lose horsepower and responsiveness when they go bad.

Tires are really personal. Obermeyer likes Dunlops, but they are “wobbly.” Nickelsen uses a lot of different tires, depending on the terrain. New Pirellis are great, especially on wet or muddy rocks. Full-Bore fronts are excellent.

Gearing down slightly may be helpful, especially if your club is into circus turns and menagerie sections. Some riders like the old metal Amal throttle better than newer plastic ones because (once thoroughly deburred), they work very smoothly, don’t deform under hand pressure, and have a very “soft” action because of the small internal drum size.

Grips are rider’s choice, but Doherty and Oury seem to be very popular. Oury supports the NATC riders with grips, for what it’s worth. Put ’em on with contact cleaner as a lubricant; when it dries, they stay put. If that doesn’t work, tape the bars with surgical or (old-fashioned) friction tape, then use gasoline to get them on. Then you have to cut them off with a knife. The other way, you can stick a long thin screwdriver down inside, give them a shot of contact cleaner and slide them right off.

Fork and shock springs sack out; replace them with stock items or trick stuff like Sammy Miller’s. Production shocks are getting better, but new Girlings and Betors are hard to beat. Téleseos are good for moved-up shocks, as are Konis because they can be rebuilt easily.

Skid plates are almost a must to keep cases intact and frame tubes under the engine from buckling up. Preston Petty and Miura Products plastic plates are good. 6061-T6 alloy (or something slightly softer) is also good. When the tubes under the engine start to deform badly, they must either be straightened, or removed and replaced—a la Ossa, Yamaha, RTL300 Honda and Sammy Miller—with an alloy plate. You can try straightening them by removing the engine and tank, supporting the lower frame at front and rear with a stout jib (4x4s or better), using a piece of oak or other hardwood to spread the impact, and wailing on the tubes with a fivepound hand maul. This works nicely once or twice; after that, the “Millerized” frame with a T-6 plate seems to be the only answer, and is not hard to do; just take careful measurements before you cut, because preloads can cause things to move after they’re separated. Pounding on chrome-moly tubes on newer bikes is rumored to be a no-no in Knowledgeable Circles—only time and experience will tell. The alloy plate replacement gives you more ground clearance anyway and looks trick. Leavitt and his buddies have been doing this for several years, and it obviously works.

4. Keep your swinging arm pivot bushings corrosion-free and lubed, or better yet drill and tap for Zerk fittings. Put them where you can get at them, don’t hide them like a Spanish engineer. Keep your steering head bearings tight, but not too tight. Check your spokes, especially on a new bike.

5. Sticky brakes kill engines in slippery sections. Take them completely apart, degrease, smooth up all mating surfaces with very fine sandpaper, eliminate rough or square edges on cams, file or sand out gouges left on the “follower” surface on the shoe, sand off obvious high spots on the shoe surface, get the whole shoe surface clean (a clean wire brush works well), grease the pivots and cam and reassemble. If they’re going to get wet, a fine spray of WD-40 or LPS-1 will help (no we haven’t flipped out, try it!) Keep cables well lubed or replace.

6. When your pegs flop, so do you! Weld on metal as necessary to get them back up at a slight angle and make new teeth. Bultaco pegs are super, so use them for a model if yours don’t measure up.

7. Leaky fiberglass tanks are revolting, make your van stink, and are dangerous. Use contact cleaner or lacquer thinner to leach oil from cracked areas after emptying the tank, clean away as necessary with a small wire wheel, and use epoxy to seal them. This works especially well on the underside leaks on Spanish tanks. Five-minute epoxy is usually better than the slowsetting kind, because it doesn’t have as much time to run all over. If you have a fiberglass tank, run a fuel filter, because the crud that comes out of these things is incredible.

8. Because of the temptation to practice trials in your backyard or neighborhood gully, please run a muffler. The Honda and Bultaco “pregnant boomerangs” are excellent examples of how a muffler can keep you popular, and smooth out the bottom-end performance on your bike.

9. Practicing: Two of the worst things you can do to yourself are: practicing the things you’re already good at, and practicing in the same area constantly. Figure out the things you can't do, and hate to do (usually they’re the same) and make yourself do those until you’re good at them. Once this happens you’ll probably find that you don’t hate them any more. If you live in an area with a nearby gully practice area and ride there all the time, don’t be surprised when you can’t ride rocks. Mick Andrews once told us that he sets up practice sections that are so horrible and scary that the things he finds in regular trials don’t bother him. This is a logical extrapolation of our previous suggestion, but don’t practice the humongous stuff by yourself. If you get hurt with no one there to help, it gives you a sinking feeling.

10. In line with suggestion nine, most people have a “good” and a “bad” side. Many people can make tight turns to the left beautifully but not to the right. There are several possible explanations. First, if you can’t turn right, you probably avoid practicing right turns. Second, your muscles may be weaker on one side; if you have to really “get out” on an off-camber, up-hill right-hander, your left leg muscles may be too weak to take much practice. Third, there’s an ergonomic factor: when you’re going left in such a turn, the throttle is right in front of you, and easy to work. Also, you can hold the bike over with your left or “downhill” hand, and it all works out rather nicely. Conversely, a righthand uphill turn puts you in an awkward position from an ergonomic standpoint: the throttle is down underneath, where you have trouble using it with any finesse because it’s under the bike, and you’re trying to exert a downward or inward pressure with the same hand. Now you have several explanations as to why it may be easier for you to turn one way than the other. Answer: practice doing the stuff you don't like.

(Continued on page 32)

Continued from page 31

11. Have you ever gotten in a spot where the bike “just wouldn’t turn?” This usually happens on uphill offcambers. The bike wants to go on across the hill rather than up. Sammy Miller calls this “machine in control.” It’s not, actually. It’s really a rider who doesn’t understand everything about making the bike turn. Elliott Schultz, who teaches Bultaco’s trials schools, showed us one solution: Keep your shoulders parallel to the bars. If you’re turning to the right, your right shoulder should be back, to pull the right handlebar back. If your shoulder is forward, it’s almost impossible to make the bike turn. If this doesn’t solve the problem completely, you may have to over-emphasize the other things which make the bike turn: weight outside, and the bike pushed over farther into the hill. Try these things one at a time, to see which one, or combination works.

12. If you’re over 30, try a kidney belt.

13. Trials setting: One way to make 80 percent of your riders learn to hate the sport is to set every trial so that your best rider wins with 20 or 30 points. This will mean that a lot of the riders will come in with 100 points or more for the same sections, crunched bikes, bruises (or worse) and a slowly but surely developing distaste for riding trials. If you’ve ever seen Bernie Schreiber, Marland Whaley or Lane Leavitt ride, then you’ll know what I’m saying. If you set sections to take points from them, the rest of us are going to be hurting just to get through! You can’t set a trial with the philosophy that “I’m going to get points from those guys,” or you’ll make it way too tough for the median rider. Some solutions to this problem:

Have “club” or “family” trials frequently to keep the interest up. Think about where your observers come from, dummies!

“Clerk” every trial before it starts; if the trialsmaster can’t clean a section in the first few rides, make him change it or throw it out. This is guaranteed to gain you at least five new enemies every year, if you’re a club officer.

Establish very specific guidelines for your trialsmasters. They won’t follow them, but at least you can browbeat them with “fair warning” when you clerk their sections.

Have enough “man-killers” every year to satisfy the hard-cases, but advertise them as such, and encourage the less advanced riders to stay away or to come and observe.

There is absolutely no excuse for dangerous sections. All they prove is that the trialsmaster didn’t have enough imagination to find or create a challenging, safe section. If you have to have sheer climbs, put catchers on them, and so forth. The first U.S. trialsmaster that kills a rider is going to have some bitter memories to live with.

Think about this: At the 1975

British Experts Trial, all but nine of 10 of the riders quit before they completed the first loop. I don’t mean that turkeys quit, I mean the cream of English trials riders. They quit because the sections were so dangerous to men and machinery as to be ridiculous. The whole thing seems to be getting out of hand. Solutions will come, but they will take vision and hard work.

Lastly, the thing we’d most like to see devloped among trials enthusiasts around the country is an analytical approach to trials riding and machine maintenance. Pick up a copy of Zen and the Art of Motorcycle Maintenance. You don’t have to be a firebreathing kid with trick reflexes and a lack of fear to be a competitive trials rider. Obviously, it helps. . .but Sammy Miller is over 40 and still capable of winning tough national events in Britain on a good day. He does this with the help of good preparation, good attitude and a good approach to practice and keeping fit. If you’re still riding trials at 40-plus, you’re hound to be better for it. It sure as hell beats watching bowling tournaments on the tube.

So, if you have questions relating to trials, let us hear from you. We’d like to know what areas you’d like explored and how the “Trials Notebook” format worked for you. Nickelsen will be at the Nationals, and both of us will be at the American Round in Washington. Talk to us there, or write c/o CYCLE WORLD, 1499 Monrovia Ave., Newport Beach, CA 92663. And keep ’em flying. joj

Now that you've mastered the intri cacies of trials riding, why not tune in to CYCLE WORLD's new how-to fea ture, "Pro Techniques for Off-Road Riding," found on page 41 of this issue.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Departments

DepartmentsUp Front

June 1976 -

Letters

LettersLetters

June 1976 -

Departments

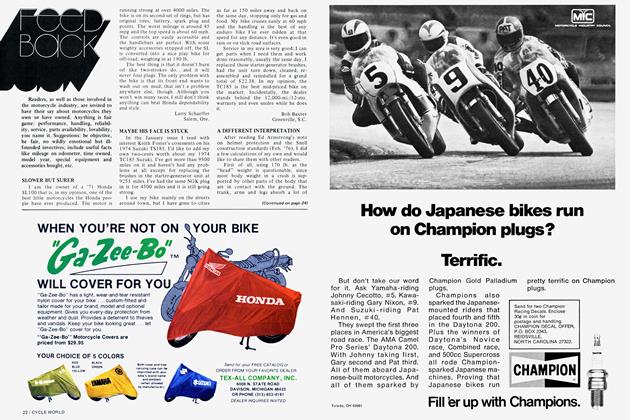

DepartmentsFeed Back

June 1976 -

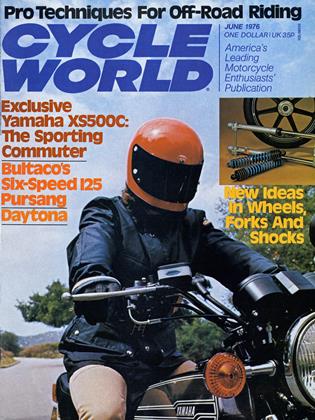

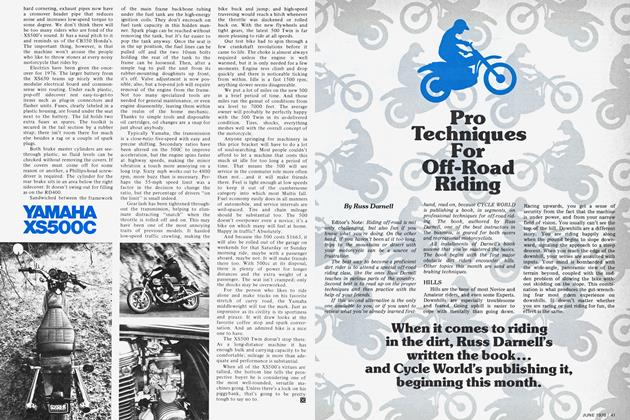

Special Supplement

Special SupplementPro Techniques For Off-Road Riding

June 1976 By Russ Darnell -

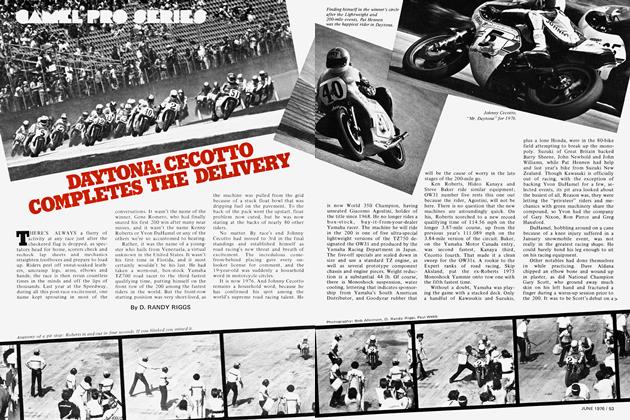

Camel Pro Series

Camel Pro SeriesDaytona: Cecotto Completes the Delivery

June 1976 By D. Randy Riggs -

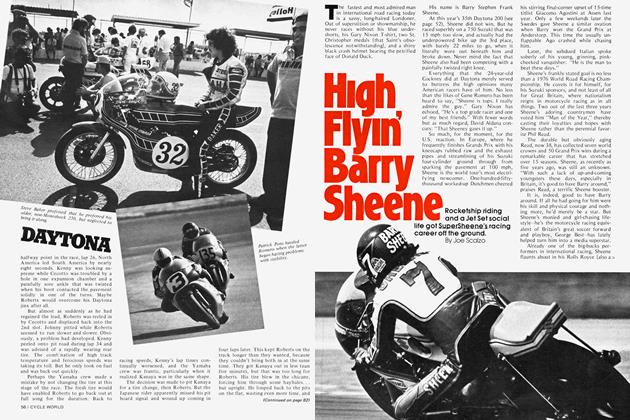

Features

FeaturesHigh, Flyin Barry Sheene

June 1976 By Joe Scalzo