and now from Dixie... the yamaha Paper Cup

John Waaser

HE STEPPED OUT from behind the immaculate Porsche with a welding torch in one hand, his soft gray coveralls contrasting with the sharp light lines of his beard, and his greasy hands fading under the presence of his twinkling eyes. He was the very picture of a typical overworked, underrecognized tuner.

“You look like a Woody Kyle type,” I said with a tone of authority that comes from knowing you’re right.

“No, I’m Woody Kyle,” said a young man standing to the welder’s left, in a clean T-shirt and sharply-creased Levis; a young man who looked for all the world like a customer of the man with the torch.

In keeping with the low-pressure aspects of this weekend’s racing, I had decided to ride the 350 Four from Massachusetts to Georgia, carrying a minimum of camera gear and clothing, so that I could enjoy the weekend, instead of working for a living. But I had run afoul of Japanese rubber; the Bridgestone original-equipment tire that had looked so good to me when I started the trip had deteriorated in the southern heat. What started as a small bald patch amid a sixteenth of an inch of tread in North Carolina, 200 miles later had worked its way half around the tire. No way would the thing get me home.

Freelance journalism being a hand-tomouth existence, I asked a local friend if he could direct me to a dealer who would sell a take-off tire cheap, or at least accept a check, since the cash situation was minimal. Said friend called Woody Kyle, a tuner of quite some local repute, who had a used tire there with lots of tread still on it, but that was no longer suited to dirt track racing, since the edge was worn off. Woody and friends were ready for me, whipped the wheel off, gave a fine demonstration of the proper use of one of those motorcycle tire changers, put the wheel back on, and lubed the chain, while not allowing me to do anything more strenuous than sip a beer—which they provided. Then they went back to putting the finishing touches on a Kawasaki cafe racer that would be ridden in the Paper Cup the next day.

The tire they had given me was an old Pirelli dirt track special. . .super hard compound. It was a mite dodgy in the wet, to say the least—and oh, did it get wet. While I was there, the heavens opened up to give an impression of what it was like to be part of Noah’s band. Lightning struck, knocking out the power in Woody’s shop, and the nearby Yamaha and Kawasaki shops. What to do? Well, back home in such a situation, people would scurry around, trying to find a way to stay on schedule and get things done without power. Down at Woody’s place, the situation just called for a little bench racing, and another case of beer.

That must be the biggest reason I enjoy heading south so much. I hate their weather, I abhor their red Georgia clay, and I especially detest the North Carolina State Police, who had just instituted a new program of radar units every ten miles and driving patrol cars down the Interstate side by side-using every available lane—at 55 mph, in an effort to enforce that limit. But 'the Southern people, epitomized here by Woody Kyle, have a way of living life to its fullest without making a rat race of it. And that’s what the Yamaha Paper Cup is all about. The Gold Cup may have started out West —and brings to mind places like Madison Square Garden—but the Paper Cup could only have originated down South.

The Georgia Road Race Association is a young group, just a little more than a year old, centered along the coastal areas of Georgia. There is actually very little in the way of a club racing scene in the northwestern corner of the state, in spite of the availability there of one of the world’s finest road racing and motocross plants. In fact, availability is the wrong word. When the GRRA approached Road Altanta about conducting races there, the circuit turned them down cold, since there was no proven profit potential, and a large racing plant costs quite a bit to throw open for two days.

Enter Yamaha, or, more specifically, the Yamaha dealers of Georgia. There are 31 such dealers, and each of them kicked in $50. The few dealers around the Atlanta area tossed in a bit more, and that was enough to guarantee the track rental. That made the situation attractive to the Road Atlanta people, and they agreed to put on the promotion. Yamaha International Corporation footed a portion of the advertising bill, since it would help publicize the Yamaha name.

The GRRA acted in an advisory capacity, writing the rules, and answering questions on procedure. Yamaha International Corporation’s southeastern office, located nearby, supplied many of 'the people to handle such chores as sign-in and tech inspection. Road Atlanta ran the whole show. It was they who took in all the entry fees, bought all the trophies, handled the advertising and promotion.

Interested parties with special skills volunteered their services in any needed capacity. One GRRA member works in the advertising art department of a local motorcycle newspaper; yet another works in the same paper’s darkroom. Together they whipped out a “diploma” for all competitors, even changing the track’s logo to substitute motorcycles for the cars normally seen over the lettering. The trophy, if any, might be put on the mantle, or in the closet, with countless others, but the Certificate of Achievement would be a constant reminder to the racers that the Yamaha Paper Cup has a significance of its own.

This loose organization of a race meet depends on a whole lot of volunteer people doing a little bit of work each. It’s the sort of thing that has failed miserably in many areas of the country. Why does it work here? The answer to that can be found in one word: enthusiasm. For it to work,

EVERY Yamaha dealer had to kick in his share, EVERY employee of YIC, and YPDI (Yamaha’s parts division), had to do a little bit of work. There would be no glory when it was over, just a lot of cleaning up. There would be no bonus in the paycheck, either, just the satisfaction of playing a part in a successful project that brought enjoyment to the smallest fraction of one percent of this country’s population.

But everybody connected with the affair radiated sunshine, even when the Georgia skies wouldn’t provide it, and exuded enthusiasm so contagious that you couldn’t feel despondent even if your bike broke in the earliest laps of practice. Yamaha’s Bill Mason summed it up this way: “It’s a Mickey Mouse thing, but it works.” Even Road Atlanta staffers gave in to the general feeling and let their hair down—to the extent that Publicity Director Mike Dowda flagged the motocross clad in white cut-off shorts.

The show was mostly a GRRA affair, but the nearby Eastern Road Race Association had agreed to hold the date free, and to play it up among its riders. Entries came from as far away as Detroit, but the “little guy” could count on getting near the front, as the biggest hotshoes present ■ were Stan Fridus in the road race, and Gordon Bowden in the motocross. In fact, the event wasn’t going to be AMAsanctioned at all until somebody remembered that Terry Tiernan, head honcho at Yamaha International, had just been elected president of the AMA, and it might be in bad form to have Yamaha’s name on a race without AMA sanction. Even so, they didn’t check too closely for your AMA card. If you showed it, fine; if you forgot, they didn’t bother to ask.

This was the second annual Paper Cup. The first had been almost a dismal failure, with only a handful of riders entered. There had been no GP class. . .the original concept of the Paper Cup was to “run whut you brung.” In order to get the entries up, they added a GP class this year, but it would still be heavily geared to Production classes and cafe bikes.

While the lack of pre-entry no doubt helped lengthen the sign-up lines, and prevented any accurate pre-race information on how many first-time racers would be there, Jake Kennington of the GRRA predicted 50 to 75 riders would make this their first-ever road race, riding their every-day street bikes. For this reason, tech inspection was very stringent, and one rider wandered off babbling something about never having had to safety wire his transmission level plug at a race before. Full leathers, helmets and gloves were also carefully checked.

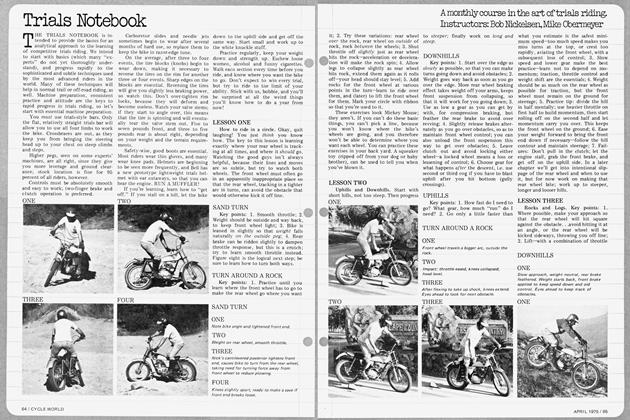

Novice racers were escorted around the track for their first few laps, under the tutelage of a more experienced rider, who showed them the lines at a low rate of speed. In spite of the wet track conditions (remember, the AMA won’t run a National here in the rain), and the large number of first timers, Saturday’s safety record showed one broken leg on the motocross course, and no serious injuries on the road circuit.

Because they used the infield motocross pits—unlike at the June National— the motocross riders did not cross the asphalt track, and both motocross and road racing could be conducted simultaneously. The heavy rain Friday night and the drizzle Saturday morning helped hold the dust down considerably on the motocross circuit, and dirt lovers found the conditions just about ideal.

The track dried during the noon hour, and the clouds finally broke, so the sun could shine by about three o’clock in the afternoon on Saturday. Saturday’s schedule was taken up by the motocross, with road racing practice scheduled only for the morning, but extending later due to the weather. Everybody seemed to be out there together, since there were only two groups of road racers for practice.

The first group included all Production classes, the Cafe class, and GP bikes up to 200cc. This great disparity in racing machinery made for a lot of passing in practice. It must have been scary as hell to ride, but it was great to photograph. Some of the first-time racers on street bikes started getting it on after only a few laps, while some of the more established racers were scratching pretty well as soon as the track dried.

Some of the guys in the Street and Cafe classes don’t actually ride the street, but keep their bikes solely for racing—and some of the cafe bikes are thinly disguised beasts resembling welltuned GP bikes, but with street-legal accouterments, even though the owners had no intention of riding on the street when they set the machines up. These were out on the track with budget specials of 125cc displacement and under in the GP class, which were really slow.

There were lots of cases of guys cutting each other off, particularly small tiddlers popping right into the line of a larger and faster bike that was rapidly closing from behind, and didn’t expect the smaller bike to shoot inside so late. For those who found they were in over their heads-and it happened frequently—the approved technique was to straighten up, hit the brakes until the very edge of the track, then coast off into the omnipresent red clay, and ride it out. These guys would invariably pop right back on the track, depositing great galloping lumps of clay on the asphalt, to the consternation of more experienced riders.

The disparity of racing machines entered was amply evident in the pits. There was a new Harley-Davidson RR250, but, after two laps of practice, it gave up the ghost with a strange drive-line snatch, some funny noises and a locked crank. There was a fabricated aluminum “monocoque,” which, if you looked carefully enough, revealed that it was slipped on over a tubular backbone. The swinging arm pivot was miles behind the transmission output sprocket (not a good design feature), and the thing bobbled its way out of every corner. But it had a unique front-end partial fairing that could provide a way to fight lift at speed, except that that doesn’t seem to be much of a problem.

There were the budgeteer specials, based on 125 Suzukis and other similar bikes, which might have been slow, but looked like an affordable way to go racing. There were street bikes with high mileage showing on the odometers, and “street” bikes with no speedometers at all; cafe bikes never designed to be ridden on the street, and cafe bikes designed expressly for the street, but which the owners thought would be fun to race. And everywhere you walked, somebody you had never seen before greeted you as an old friend.

One problem during the motocross, which was corrected to some degree during Sunday’s road racing, was that the announcer kept referring to riders by their numbers. Any fool interested in watching the race knows what number machine is in the lead, he’d like to know the name of the rider. Another indication that the promoters weren’t exactly with it was the fact that the 125cc class motocross had some 85 entries—split 50 in the first qualifier and 35 in the second. Yet an equal number of riders would qualify from each. I’ll ride the second qualifier, thank you. . . .

Another problem was ambulance access to the motocross course. An injured rider had to be placed on a stretcher, carried to the fence, passed over two fences—a snow fence and then a chain link job—to the ambulance crew down on the road racing circuit. Pity the poor motocrosser who gets injured in an out-of-the-way place on the course. New England riders, used to what may well be the best motocross ambulance protection in the country, would probably refuse to ride under such conditions.

The best motocross race of the day was in the Open class. Gordon Bowden, an Irish rider with an established local reputation, had picked up a pair of monoshock Yamahas in Canada. . .a 250 and a 360. Yamaha had chosen this race to introduce the new production monoshock machines. One would be ridden by l 7-year-old Roger Smith, who rides out of the Dirt Bike Shop in Tennessee, but the bike was fettled by Fred Speet, the gentleman who conducts Yamaha’s service schools in the Southeast.

Compared to what the average rider out there could boast, it was trick, and it was quick. But Roger had problems in the first moto. The gas tank leaked, and gas was dripping onto the high-tension lead or some equally vulnerable part of the electrics, causing a high-rpm misfire. Since the monoshock’s gas tank is a different unit from the standard YZ’s, the only available replacement tank was the one on Bowden’s 250.

Roger had finished 2nd to Bowden in the first moto, and Gordon refused to loan the tank to Yamaha International or Roger. They obviously had to do something, so they patched the leak with chewing gum and duct tape. The second moto was a corker. Roger held the lead for much of the race, and his regular sponsor’s entourage was going wild in the VIP lounge at the top of the press tower. Then Bowden passed for a lap or two.

On the penultimate lap, Roger regained the lead, but on the last go-round he made an error in judgment while preparing to lap two riders who were traveling side by side up the back hill. Bowden scooped him badly then, but Roger got on the gas and came up even as they crossed the built-up jump. Roger had been flying farther and faster off that jump than anybody all day, and he managed to land ahead of Gordon. It was a simple matter to squeeze the older rider out on the last turn and blast up to the checkered flag in the lead, winning both the moto and the overall victory.

With close to 300 motocrossers and nearly 200 road racers present, there was some grumbling—particularly among the motocrossers—that four trophies per class simply wasn’t enough. And while the lack of a purse kept most of the real professional hot shots away, I heard one comment that the presence of Bowden, even though he got beat, was in violation of the spirit of the Paper Cup. But the only way to eliminate him would be to eliminate anyone holding an AMA professional licenseand that’s too fine a line for road racing, where lesser AMA types consistently support club racing, and club racers have to ride AMA professional events to fill out their annual schedules.

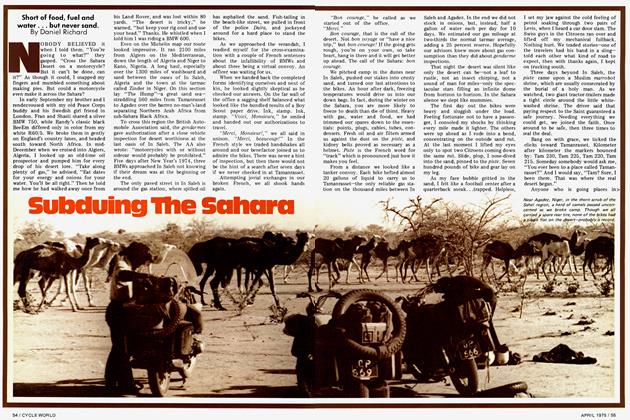

Sunday dawned a bit more promising than Saturday, weather-wise, and by noon it was one of those days we all yearn for in mid-winter. Too hot to dress up in full leather, perhaps, but just right for spectating. So after practice, when they called for a trials exhibition during the noon hour-and-a-half (Road Atlanta’s silent period by local regulation), everybody came down to watch. It was good, informal fun, as riders slid, slipped, and spilled into a small stream of red Georgia water. They clambered over the road course’s Armco barrier, climbed log piles, and then a couple of them even managed to ride over a five-or-six-inch-diameter sewer pipe spanning the stream.

Then the trials bikers held a small wheelie contest. After they’d done their thing—and not for very far, at that— some kid on an English lightweight-type 10-speed bicycle, with one hand on the bar and the other busy waving to the spectators, proceeded to go farther monowheel than any of the motorcycles had. Eat your hearts out, guys. . . .

Big winners in the road race included Dennis Lamb and Dave Stanton. Since it was legal to enter the same machine in more than one class (you could go larger, but not smaller), Lamb rode his 250cc Yamaha in the 350cc and 500cc Production classes and the Open class, racking up a 1st, a 3rd, and a 5th respectively. Stanton won the 500cc Production and the Open Production classes, as well as taking a 6th in the Open Cafe class on his Kawasaki.

Lamb’s 3rd in the 500cc race was actually a really good dice for 2nd most of the way. The 250cc GP class saw a neat five-way dice for 1st throughout much of the event, with a fair amount of position juggling. Bill Harding had the early lead, then dropped to 3rd, got back to 2nd, then back to 3rd again, finally finishing 2nd to L.G. Amos. Danny Hyatt held the lead for awhile, but finished 3rd. One problem for some of these guys may have been that they didn’t know the finish was approaching. Know what they used for a white flag? A Holiday Inn towel. . .complete with green stripe.

AÍ Kowitz, of Team Jewish, did his thing in the Cafe class with a Kawasaki. The Kaw that Woody Kyle had been working on was out of the qualifying heat in one of the weekend’s more spectacular accidents; the rider missed a shift, apparently, and broke concentration while trying to select a gear. . .any gear. He went off the end of the straightaway at 100-plus mph, into the Armco barrier, and sustained various minor injuries to his bod—but nowhere near the sort of injuries anyone who saw it would have expected.

results

MOTOCROSS

ROAD RACE

(Continued on page 88)

Continued from page 47

And Ron Mass, sponsored by the Atlanta Motorcycle Institute, one of the myriad motorcycle mechanic training schools that have sprung up over the country, bested a small field in the Open GP class. If AMI’s students learn by doing, their instruction must be pretty good.

And a special award for idiot of the day goes to Jay Word, who managed to make it through Saturday’s practice okay, but who left his ignition key home on Sunday.

After a mass awarding of trophies in Victory Lane, everybody simply loaded up and headed for home. Many of the motocrossers had gone on Saturday, to race somewhere else on Sunday. In fact, the motocrossers, for the most part, are a completely different crowd from the road racers. It would seem that if entries get too numerous, the motocross could be cut without really getting anybody mad—except that the organizers seem to have found a way to neatly integrate the two types of racing so that they don’t interfere with each other. And, of course, one should remember that Yamaha sells an awful lot of motocross machines. . . .

Yamaha’s ebullient Bill Mason insists that they simply cannot get too many entries. He says they’ll have better sign-up facilities next year (pre-entry, with late entries permitted at the track, would help), and there certainly seemed to be room on the track for more riders in most classes. So a few more riders will only mean a few more hassles. And it might work, because the people here uniformly gave the impression that nobody felt obligated to work; they were here because they felt like it.

So if you’ve got a good racing plant nearby, and they won’t let you use it, go see your local dealer. If you can spark enthusiasm in a bunch of dealers, this could be a whole new way to start racing in your area. It doesn’t have to be a Yamaha dealer, either, except. . .well, the Honda Paper Cup just wouldn’t sound right.